Pranay Kotasthane

Three methods of varying intensity have been tried over the last two years

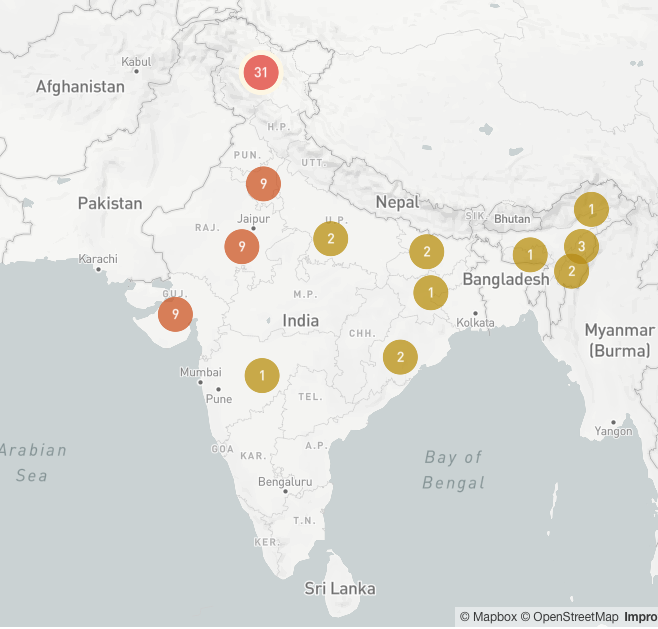

Suspension of internet services has become an integral part of the toolkit for preventing large-scale violence. In India, it is the conflict-ridden Jammu & Kashmir state where this strategy has been deployed with highest intensity over the last two years.

the valley has seen network shutdowns 28 times in the last five years.. India saw 14 cases of internet shutdown in 2015. This number rose to 30 in 2016. This year has already seen 17 cases of Internet shutdowns so far — and five of them have been in Jammu and Kashmir [Mint, May 4, 2017].

Going one-step further, there have been three types of interventions that have been deployed in this broader category of shutting the internet down.

The first category comprises of shutdown on mobile internet services i.e. blocking 2G, 3G, and 4G data services in an area. This has been the most frequently used internet shutdown technique in J&K. It comes in two variants, ban on postpaid services and ban on prepaid services. Generally, mobile internet services are restored faster on postpaid connections when compared to prepaid ones.

For example, to quell the protests after the the killing of Hizbul Mujahideen militant Burhan Wani in July 8, 2016, mobile internet services were banned. While the internet ban was lifted for postpaid connections on November 16, 2016, prepaid consumers were able to access internet only from January 28th, 2017 — after more than six months it kicked in.

The second category is a superset of the first category. Besides all restrictions on mobile internet, this category includes a ban on wired broadband access. This has generally been used more cautiously, and in smaller chunks of 4–5 days. For example, during the same period in the second half of 2016, when mobile internet services were banned, broadband internet services were blocked starting 13th August (for 5 days) and again on 12th September (for another 5 days).

The third category is a new one. It was deployed starting on April 26th this year. This time around, URLs of 22 social networking services were directed to be blocked for one month until further orders. People then took to VPNs in order to access the internet once high-speed (3G) internet was available to them.

Blocking access to internet has huge negative externalities — though the aim is to prevent nefarious elements from spreading rumours, it curtails civil liberties of all individuals in the affected area. Hence, it should ideally never be used. However, given that radically networked individuals have used the internet to mobilise people for violence—in Muzaffarnagar (2013), Dadri (2015), and Gujarat (Patidar agitation, 2015)—there is a case that when the clear and present danger doctrine applies, it is alright to impose restrictions on internet usage. But the threshold at which such a ban should kick in and the intensity of enforcement across areas needs a thourough reassessment so that this provision does not get misused.

No comments:

Post a Comment