By Russell A Berman and Arno Tausch for Institute for National Security Studies (INSS)

According to the polling data collected by Russell Berman and Arno Tausch, 1) 8.3% of Muslims worldwide support the so-called Islamic State; 2) 18% of Syrian refugees sympathize with the group, while 30% of them want to establish a theocratic state in their war-torn country; and 3) 52% of all Arabs agree that US meddling in their region justifies terrorist responses. These percentages, Berman and Tausch are quick to note, tell a more complex and differentiated tale than one might first suspect, but they also raise legitimate questions about the hostility being directed towards certain Western immigration policies.

The Wind of Change across Europe

With elections in 2017 in key European Union states (France: presidential, April 23, second round May 7, National Assembly, June 11, second round June 18; Germany: Federal Diet, September 24; Netherlands: Second Chamber, March 15),1 an intensified debate about migration to Europe and Middle East terrorism – its origins, trajectories, dangers, and the extent of its mass support – is highly likely. Marine Le Pen, leader of the far right Front National in France, predicted that European elections in 2017 will bring a wind of change across the region.2 With the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom and Donald Trump’s US presidential victory, far right political parties throughout Europe are now capitalizing on Euroscepticism and anxieties about migration.3

German Chancellor Angela Merkel appears to have responded to Le Pen’s challenge by defending her own refugee policy as an act of moral and legal obligation by a “state of laws,” while asserting that Europeans must stand by the principle of offering asylum to all those fleeing war and oppression.4 The fact that the Berlin terrorist Amis Amri was shot in Milan, Italy, after crossing several European borders following his attack in the heart of Germany, where he had previously applied for asylum, further fuels the controversy about the alleged failures of existing European refugee, immigration, and security policies.5

The debate intensified because Merkel’s decision to welcome hundreds of thousands of refugees from the Middle East and North Africa during the summer and fall of 2015 was designated “a catastrophic mistake” by Donald Trump.6 Similar to right wing European populist opposition politicians, who are poised to benefit from the upcoming European elections, Trump asserted that “people don’t want to have other people coming in and destroying their country.” Trump’s own election campaign rhetoric included a call to ban Muslims from entering the US until “our representatives” find out “what the hell is going on there.”7

To shed light on “what is going on there,” this article examines selected open sources regarding attitudes toward terrorism, terrorists, and other extremist groupings. This social scientific evidence paints a complex picture. On the one hand, it finds considerable support for terrorism among large sections of Arab and Muslim publics, although the support is not at all uniform or undifferentiated. On the other hand, despite considerable hostility toward the United States and Israel, there are large sections of the Arab and Muslim publics that do not support terrorism. It is therefore difficult to draw unambiguous conclusions regarding these publics or to derive a simple formula for refugee or immigration policies. It is not, however, difficult to recognize significant levels of support for terrorism, which could presumably justify certain restrictive refugee and immigration policies.

Reactions by incumbent Western political leaders to the Trump’s administration’s first attempt at a travel ban against nationals from Libya, Yemen, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Somalia, and Sudan in late January 2017 were quick and predictable.8 Merkel said that she “regrets” the move.9 Her opposition was echoed throughout Europe, as well as by Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. However, even as these voices were criticizing the US administration’s efforts to limit entry for a temporary period, European states, including Germany, were taking their own steps (with Turkish cooperation) to reduce the inflow of refugees and accelerate deportation processes of individuals whose applications for refugee status were denied.

Despite Merkel’s criticism of the Trump administration’s restrictive immigration policy, Europe arguably stands at the dawn of a post-global and Eurosceptical era driven by nationalistic movements that have developed in response to increased immigration from Africa, Asia (including Turkey), and even parts of Europe itself (the Balkans, for example).10 The rise of centrifugal movements in key EU countries, the argument runs, reflects the weakening of the pan-European spirit and the gains of extreme nationalism at its expense.11 The severe economic crisis that has particularly affected Europe’s south since 2008 and threatens the very existence of the European Monetary Union is not the focus of this essay, but it has certainly amplified these centrifugal tendencies.12

Europe’s Low Effectiveness in Fighting Terrorism

Europe’s effectiveness in combating terrorism has frequently been diagnosed as inadequate.13 Solid evidence is mounting with regard to the devastating nature of global Islamist terrorism and its thousands of victims each month, from Nigeria to Southeast Asia and also, increasingly, in Europe.14 A recent survey by the French Daily Le Monde reported that in Europe alone, there have been 2239 victims of Islamist terrorist attacks since 2001.15 At the same time, an intellectual climate remains that is predisposed to minimize or even deny the reality of the low intensity guerrilla warfare carried out by Islamist groups against the Western democratic order.16 The German newspaper Südkurier, for example, went so far as to assert that in Germany it is more likely to be struck by lightning than to be killed by a terrorist attack.17 Obviously statistics can be manipulated to trivialize any danger or to suggest that one should regard terrorist deaths like lightning, an unavoidable natural phenomenon. Such hiding one’s head in the sand, however, is the worst strategy for confronting international terrorism.18 Instead we propose proceeding empirically by discussing some new international survey results about the genuine extent of support for terrorism in the Arab world in particular and in the Muslim world in general. Is it 1 percent, 10 percent, 30 percent, or 50+1 percent?19

Statistical Data on Arab Support for Terrorism

The essay relies on the statistical analysis of open survey data and is based on the commonly used statistical software IBM SPSS XXIV, utilized at many universities and research centers around the world.20 The program contains nearly the entire array of modern multivariate statistics,21 and any researcher should be able to arrive at the same results as we do here. Clearly the analysis below provides only a first attempt to measure “support” for terrorism, and later research on the subject should distinguish between different types and degrees of support for terror.22 However, the available data allows researchers to distinguish between those who strongly support terrorist organizations like Hamas, Hezbollah, and al-Qaeda, and those who say that they just “support” these terrorist organizations. From the available data, one could develop fine-tuned social profiles of strong terror supporters on a country by country basis.

The sources used in this article are:

a. The Arab Opinion Index of the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies in Doha, Qatar.23 Since 2012, this think tank has published regular professional surveys of public opinion in the Arab world, and the 2015 Arab Opinion Index is the fourth in a series of yearly public opinion surveys across the Arab world.24 The 2014 Index was based on 21,152 respondents in 14 Arab countries, and included 5,466 Syrian refugee respondents living in refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and northern Syria along the Turkish-Syrian border. The 2015 Index is based on the findings from face-to-face interviews conducted with 18,311 respondents in twelve Arab countries: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq, Jordan, the Palestinian territories, Lebanon, Egypt, Sudan, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, and Mauritania. Sampling followed a randomized, stratified, multi-stage, self-weighted clustered approach, giving an overall margin of error between +/- 2 percent and +-3 percent for the individual country samples. With an aggregate sample size of 18,311 respondents, the Arab Opinion Index is currently the largest public opinion survey in the Arab world.

b. The Arab Barometer, Wave III. This openly available original survey data allows researchers free direct access to the original data for multivariate analysis.25 The third wave of the Arab Democracy Barometer was fielded from 2012-2014 in twelve countries: Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, the Palestinian territories, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Tunisia, and Yemen. Like the first and second waves, the third wave seeks to measure and track civilian attitudes, values, and behavior patterns relating to pluralism, freedom, tolerance and equal opportunity; social and inter-personal trust; social, religious, and political identities; conceptions of governance and the understanding of democracy; and civic engagement and political participation. Data from the third wave became publicly available in the fall of 2014.26

c. The Pew Spring 2015 Survey.27 The survey, conducted from March 25 to May 27, 2015, is based on 45,435 face-to-face and telephone interviews in 40 countries with adults 18 and older.28

Because of the current importance in the fight against global terrorism, the first question concerns rates of explicit support for the Islamic State. To be sure, a verbal expression of support is not identical with a willingness to provide material support or to participate directly in terrorist activities; nonetheless the size of the supportive cohort provides an approximate indication of the base from which the Islamic State could potentially draw future militants. Since “don’t know” and “refused to answer” distort the final picture of the survey results, the focus here is on the valid answers.29

8.3 Percent of Muslims Worldwide Support the Islamic State

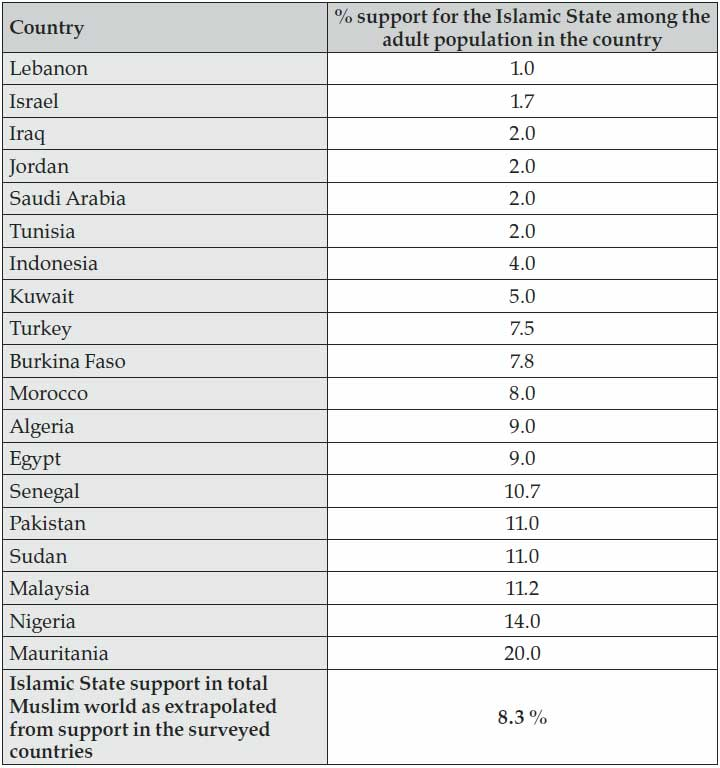

Table 1 summarizes the available estimates of Islamic State favorability rates (strong support + some support), compiled from the Pew and ACRPS data:

Table 1. Support for the Islamic State30

18 Percent of Syrian Refugees Sympathize with the Islamic State; 30 Percent Want a Theocratic State

According to the ACPRS data, support for the Islamic State among Syrian refugees in the Middle East is 18 percent.31 The ACRPS Syrian refugee poll was based on respondents from 377 population centers inside and outside official refugee camps registered by the UNHCR. The sampling procedure was a multi-staged clustered approach with an error margin of +-2 percent. This analysis of Syrian refugee opinion is the largest of its kind in the region, and also reveals that at least 30 percent of the interviewed representative Syrian refugees want a religious state as a solution to the conflict, while 50 percent prefer a secular state, and 18 percent are impartial (2 percent did not know or declined to answer).32

No survey to date has examined the political opinions of the hundreds of thousands of refugees who entered Europe since the onset of the European refugee crisis in the summer of 2015, so the ACPRS survey results, which clearly suggest that nearly every fifth Syrian refugee sympathizes with the Islamic State, and every third wants a religious state (based on sharia), can potentially have a considerable impact on political debates in Europe. Yet without a definitive survey of the population that arrived in Europe, it is not possible to exclude the hypothesis that those refugees differ on these points from those who remained in the Middle East.

A Long Asymmetric War Ahead?

Beyond the data on Syrian refugees, evidence shows that after properly weighting the data for population sizes of the different countries concerned, 8.3 percent of the surveyed population in Muslim-majority countries hold sympathies or even strong sympathies for the Islamic State. This would imply a potential of more than 80 million Islamic State supporters, again with the qualification that verbal expression of support should not be equated with a credible predisposition to participate in violent militancy. If Table 1 also properly reflects the opinion structure of the Muslim world in general, the numbers suggest a milieu33 of some 130 million people who constitute the global hard core of the Islamic State support. Compare this to the comparatively small number of the 50,000 hard core Roman Catholic Northern Irish men and women who voted for the political wing of the terrorist organization IRA, the Sinn Féin Party, through the 1970s, 1980s, and beyond among a total Roman Catholic Northern Irish population of half a million people. The IRA could mobilize some 1500 to 2000 fighters on the terrorist front, and the British military, arguably one of the best trained and equipped armies in the world, had to deploy no fewer than 15,000 to 20,000 soldiers to conduct this asymmetric warfare, only to arrive at a standstill after decades of fighting and bloody conflict.34 The lesson from Northern Ireland regarding the size of the military response relative to the scope of popular support suggests the need for enormous resources to mount an effective response to contemporary Islamist terrorism. Of course the cases are in many ways not comparable, given the topography, the political context, and the profound changes in military technologies.

52 Percent of All Arabs Favor Terrorism against the United States; 48 Percent Oppose

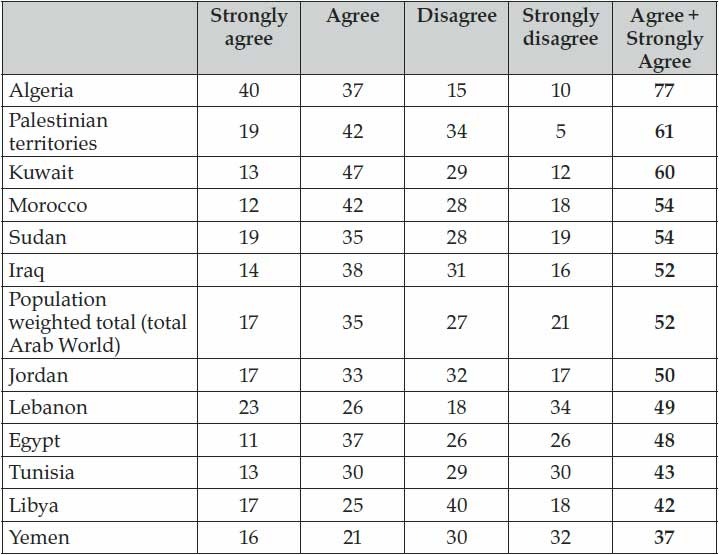

Data indicates that more than that nine out of ten Muslims around the world do not support the Islamic State, which suggests that policies that target all Muslims would be inappropriate and could run the risk of pushing the non-supporters into the supporting camp. Nonetheless the population that does in fact express support for the Islamic State is numerically large. Moreover, support for the Islamic State is only one indicator. Table 2 summarizes data in response to a broader question, with results demonstrating that 52 percent of the entire Arab world, based on the surveys in twelve countries and weighted by population size, agree or even strongly agree that “United States interference in the region justifies armed operations against the United States everywhere.” To be sure, 48 percent of the Arab population reject or strongly reject this proposition, and are willing to say so to an unknown interview partner. There may well be additional opponents of anti-US violence who are nonetheless unwilling to disclose their position for fear of retaliation. However if that speculation would suggest raising the 48 percent by an unknown supplement, a corollary methodological skepticism could operate in the other direction: clandestine supporters of anti-US violence who hide their opinion in order to evade potential consequences. Although the two shadow figures may not be of equal size, they cancel each other out as methodological speculations. Ultimately one can claim that the Arab world is evidently split on the willingness to view violence against the US as justified, and it is similarly clear that parts of the population prepared to support such violence nonetheless oppose the Islamic State, i.e., one can oppose the Islamic State but still advocate violence against the US.

Table 2. Mass Support for Anti-American Terrorism in the Arab World (valid percentages and population weighted totals, in percent)

Note: Responses to the question by the Arab Barometer Survey: “United States interference in the region justifies armed operations against the United States everywhere”

Support for Specific Terrorist Groups

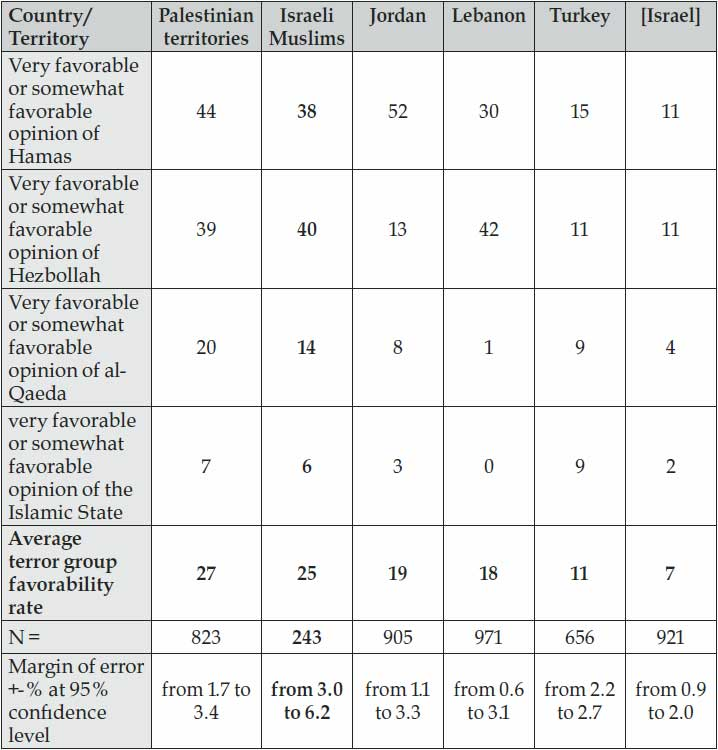

Table 3 analyzes the support rates for several terrorist groups competing with the Islamic State in the Middle East: Hamas, Hezbollah, and al-Qaeda, with similarly equivocal results. On the one hand, overall terror support rates in the entire State of Israel now reach two digit levels (in the case of Hamas and Hezbollah), and with even 4 percent in the case of al-Qaeda and 2 percent in the case of the Islamic State.35 On the other hand, only in one Middle East country (Jordan) does one single terrorist group (Hamas) command an absolute majority of support, while in all the other surveyed countries and territories, neither Hamas nor Hezbollah (let alone al-Qaeda) attracts majority support. Majorities in Arab countries evidently oppose demagogy, chauvinism, and violence.

Table 3. Support in the Middle East for Specific Terrorist Groups (percent)

Source: Pew Spring 2015 Survey

A final question concerns whether or not religious minority groups in the Middle East fit into the larger picture. Statistical methodology demands extra care in evaluating the results from the small samples that generated the following results.36 Nonetheless, the results for the Christian minorities in the Middle East may be surprising to those who assume that Christians in the Middle East might be immune to radical Arab nationalism.37 In Egypt, some 30 percent of the 50 interviewed Christians38 hold open sympathies for terror strikes against the United States as “revenge” for their policies in the Middle East, and in Lebanon, 43.40 percent of the interviewed 440 Christians hold this view.39 Among the Christians in the Palestinian territories, the same sentiment seems to apply.40 It may be the case that with regard to anti-Americanism, Christian populations in the region behave like their Muslim compatriots, although the dynamics in the individual settings may differ, which would require more textured, qualitative research.

Conclusions and Prospects

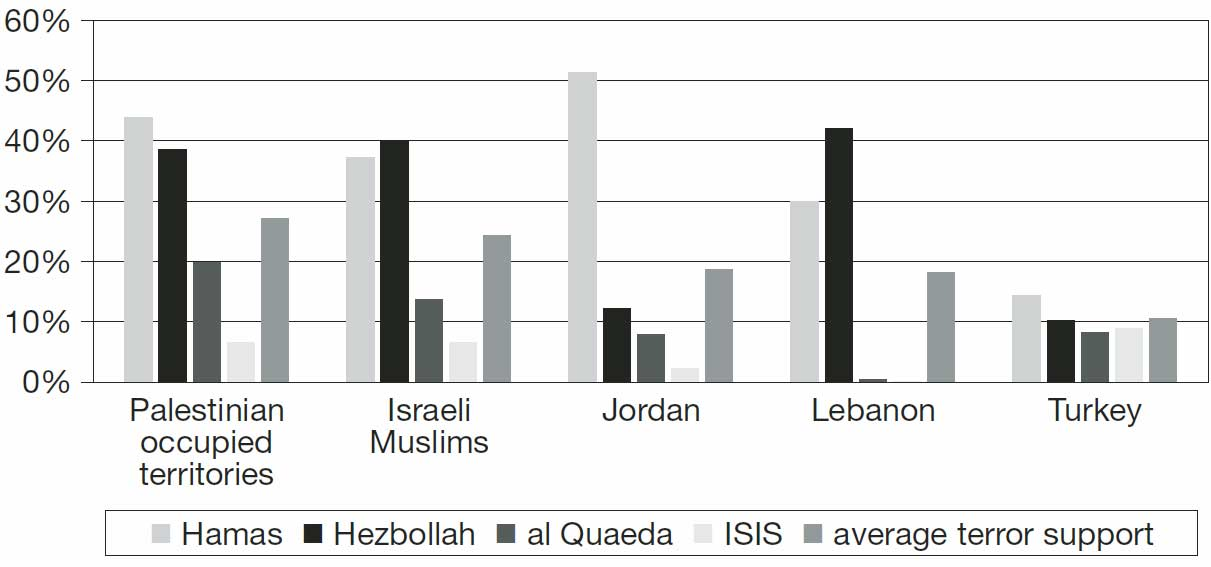

This article attempts to provide a differentiated picture of terror support rates among populations in the Arab world and in the Muslim world in general. The available surveys on the one hand suggest that among Syrian refugees in the Middle East, there is a considerable rate of support for the Islamic State – 18 percent. The analysis of Syrian refugee opinion also reveals that no fewer than 30 percent of the interviewed representative Syrian refugees prefer a religious state as a solution to the current conflict. Such results suggest that for some refugees, opposition to the Assad regime could produce aspirations for an Islamist outcome, for which the Islamic State represents one of several competing vehicles. Figure 1 presents a final synopsis of the empirical results.

Figure 1: Support for Terror in the Middle East

In conclusion, the data presented here drawn from several public opinion polls presents a complex picture of support for terrorism in the Arab world. It is likely that this complexity will disappoint both extremes in the intensifying debate in Europe and the US concerning refugees, immigration, and terrorism in an increasingly polarized political terrain. It is clear that the vast majority of the polled populations oppose the Islamic State, indicating that a “Muslim ban” would not contribute to the effort to defeat the Islamic State and could well be counterproductive by nourishing the Islamic State narrative that the West is Islamophobic. This conclusion obviously runs counter to the anti-immigrant claims of the national populist politicians, such as Trump, Le Pen, Wilders, and others. Yet the immigration-friendly camp must recognize that there is a nearly 10 percent support rate for the Islamic State and, with regional variation, higher support for other Islamist groups generally associated with terrorism. Even if such evidence is understood to count those who are only prepared to provide verbal support, rather than violent participation, the size of the cohort with violent inclinations remains disturbing. It would therefore not be unreasonable to exercise some caution in refugee and immigration policy, be it through efforts to screen for radical sympathies, no matter how difficult such “vetting” will turn out to be, or through the establishment of safe zones, to reduce the refugee or immigrant inflow.41The overall size of the population indicating some support for violence indicates that the international system will face security problems from this front for the foreseeable future.

Notes

1 International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) “Election Guide,” Washington D. C., 2017, http://www.electionguide.org/elections/upcoming/. All downloads as of February 19, 2017.

2 “‘Europe Will Wake Up in 2017,’ Le Pen Says in Germany,” The Local de, January 21, 2017, https://www.thelocal.de/20170121/europe-will-wake-up-in-2017-le-pen-says-in-germany.

3 Ibid.

4 Patrick Donahue, “Merkel Hits Back at Populists in Defense of Refugee Stance,” Bloomberg News, January 23, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/politics/articles/2017-01-23/merkel-hits-back-at-populist-wave-in-defense-of-refugee-stance.

5 “Europe’s Open Borders ‘Pose Huge Terrorism Risk,’” Sky News, December 24, 2016, http://news.sky.com/story/how-was-berlin-christmas-marketattacker-able-to-cross-three-borders-10706430.

6 “Donald Trump Says Merkel Made ‘Catastrophic Mistake’ on Migrants,” BBC News, January 16, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-uscanada-38632485.

7 Jenna Jonson, “Trump Calls for ‘Total and Complete Shutdown of Muslims Entering the United States,’” Washington Post, December 7, 2015, https://goo.gl/gFzXiy.

8 Azadeh Ansari, Nic Robertson, and Angela Dewan, “World Leaders React to Trump’s Travel Ban,” CNN, January 31, 2017, http://edition.cnn.com/2017/01/30/politics/trump-travel-ban-world-reaction/. As to the Trump administration’s second attempt at a travel ban, see Charlie Savage, “Analyzing Trump’s New Travel Ban,” New York Times, March 6, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/06/us/politics/annotated-executiveorder-immigration-travel-ban.html?_r=0.

9 Will Worley, “Germany’s Angela Merkel Attacks Donald Trump for Targeting ‘People from Specific Background or Faith,” The Independent, January 29, 2017, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/donald-trump-muslim-ban-germany-angela-merkel-immigration-refugeeexecutive-order-a7551641.html.

10 Adi Kantor and Oded Eran, “2017 – A Year of Difficult Tests for Europe,” INSS Insight No. 893, February 7, 2017, http://www.inss.org.il/index.aspx?id=4538&articleid=12976.

11 See also Arno Tausch, “Muslim Immigration Continues to Divide Europe: A Quantitative Analysis of European Social Survey Data,” Middle East Review of International Affairs 20, no. 2 (2016): 37-50.

12 Leonid Grinin, Andrey Korotayev, and Arno Tausch, Economic Cycles, Crises, and the Global Periphery (Switzerland: Springer International Publishers, 2016).

13 William Adair Davies, “Counterterrorism Effectiveness to Jihadists in Western Europe and the United States: We Are Losing the War on Terror,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, just-accepted (2017); James J. Wirtz, Understanding Intelligence Failure: Warning, Response and Deterrence (London: Routledge, 2016); Rose McDermott, Intelligence Success and Failure: The Human Factor (Oxford University Press, 2017); and Mark Bovens and Paul ‘t Hart, “Revisiting the Study of Policy Failures,” Journal of European Public Policy 23, no. 5 (2016): 653-66. On the intelligence failures leading up to the Berlin terror attacks see also “Blame Traded over Berlin Truck Attack,” Deutsche Welle, February 13, 2017, http://www.dw.com/en/blame-traded-over-berlintruck-attack/a-37538489.

14 Global Terrorism Index 2014: Measuring and Understanding the Impact of Terrorism (London: Institute for Economics and Peace, 2015), http://economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Global-Terrorism-Index-Report-2014.pdf; and Peter R. Neumann, The New Jihadism: A Global Snapshot. International Center for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence, 2014.

15 “Les Attentats Terroristes en Europe ont Causé Plus de 2 200 Morts depuis 2001,” Le Monde, March 24, 2016, http://mobile.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/visuel/2016/03/24/les-attaques-terroristes-en-europe-ont-fait-plus-de-1-800-morts-depuis-2001_4889670_4355770.html.

16 Ekaterina Stepanova, “Regionalization of Violent Jihadism and Beyond: The Case of Daesh,” Interdisciplinary Journal for Religion and Transformation in Contemporary Society 2, no. 2 (2016): 30-55.

17 “Warum Vieles Wahrscheinlicher Ist, als Opfer eines Terroranschlags zu Werden,” Südkurier, April 14, 2016, http://www.suedkurier.de/nachrichten/panorama/Warum-vieles-wahrscheinlicher-ist-als-Opfereines-Terroranschlags-zu-werden;art409965,8657606. For an analysis of anti-Americanism in Europe as the driving force behind policies leading to insecurity and a weakening of the transatlantic alliance, see also Russell A. Berman, Anti-Americanism in Europe: A Cultural Problem (Stanford: Hoover Press, 2004).

18 See also Arno Tausch, “The Fertile Grounds for ISIL Terrorism,” Telos: Critical Theory of the Contemporary 171 (summer 2015): 54-75, and Arno Tausch, “Estimates on the Global Threat of Islamic State Terrorism in the Face of the 2015 Paris and Copenhagen Attacks,” Middle East Review of International Affairs, 2015, http://www.rubincenter.org/2015/07/estimateson-the-global-threat-of-islamic-state-terrorism-in-the-face-of-the-2015-parisand-copenhagen-attacks/.

19 For some preliminary multivariate results about the quantitative relationships between antisemitism and Islamism see Arno Tausch, “Islamism and Antisemitism: Preliminary Evidence on their Relationship from Cross-National Opinion Data,” Social Evolution & History 15, no. 2 (2016): 50-99.

20 IBM SPSS SPSS Statistics, http://www-03.ibm.com/software/products/en/spss-statistics.

21 Frederick J. Gravetter and Larry B. Wallnau, Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences (Boston, MA: Cengage Learning, 2016); and Keenan A. Pituch and James Paul Stevens, Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences: Analyses with SAS and IBM’s SPSS (London and New York: Routledge, 2016).

22 The authors would like to thank the reviewers of this article for this important point.

23 Arab Opinion Index, Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, Doha, Qatar, 2017, http://english.dohainstitute.org/portal. As this article goes to the press, results of the Arab Opinion Index 2016 are beginning to emerge.

24 Arab Public Opinion Programme, Arab Opinion Index 2015. In Brief, Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, Doha, Qatar, 2016, http://english.dohainstitute.org/file/Get/6ad332dc-b805-4941-8a30-4d28806377c4.

25 Arab Barometer, Arab Barometer III, Center for Strategic Studies in Jordan (CSS), Aman, Jordan, 2017, http://www.arabbarometer.org/content/arabbarometer-iii-0. The available codebook describes the survey and sampling techniques for each country covered by the survey.

26 As stated on the website, “the operational base for the third wave is the Center for Strategic Studies in Jordan (CSS). This third phase was funded by the Canadian International Research and Development Centre (IDRC) and the United States Institute for Peace (USIP).”

27 Global Attitudes and Trends, Pew Research Center, 2017, http://www.pewglobal.org/international-survey-methodology/?year_select=2015. This site describes the sampling and survey methods for each country, included in the survey.

28 Spring Survey 2015, Pew Research Center, 2017, http://www.pewglobal.org/2015/06/23/spring-2015-survey/.

29 We follow here a broad methodological tradition in international survey research, connected with the World Values Survey; see especially Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart, Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

30 Total country population figures to calculate the overall population-weighted averages for the entire region were taken from successive issues of Der Fischer Weltalmanach (Fischer: Frankfurt am Main 2013 and subsequent issues). For some countries, both ACPRS and Pew report results are very similar. In such a case, the ACPRS results are reported here, while Table 3 is based on Pew. For an easily readable introduction to opinion survey error margins, see the Cornell University Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, “Polling Fundamentals – Total Survey Error,” Cornell University, 2017, https://ropercenter.cornell.edu/support/polling-fundamentals-totalsurvey-error/. Readers more interested in the details are referred to Langer Research Associates, “MOE: Margin of Error Calculator or MOE Machine,” Langer Research Associates, http://www.langerresearch.com/moe/. At a 5 percent Islamic State favorability rate, error margins for our chosen samples of around 1.000 representative interview partners for each country are +-1.4 percent; at a 10 percent favorability rate, the error margin is +-1.9 percent, and at a 15 percent favorability rate the margin of error is +-2.2.

31 Spring Survey 2015; Datasets, Pew Research Center, 2017, http://www.pewglobal.org/category/datasets/; Arab Opinion Index, http://english.dohainstitute.org/content/cb12264b-1eca-402b-926a-5d068ac60011; and “A Majority of Syrian Refugees Oppose ISIL,” Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, Doha, Qatar, 2017, http://english.dohainstitute.org/content/6a355a64-5237-4d7a-b957-87f6b1ceba9b.

32 “ACRPS Opinion Poll of Syrian Refugees and Displaced Persons,” Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, http://english.dohainstitute.org/file/Get/44ce127c-5cac-4fe3-9959-579062a19748.

33 In calculating absolute numbers of terror supporters one would have to take into account that surveys usually reflect the opinions of adults only. Our figures are thus only a rough first approximation, assuming that that there are 1.6 billion Muslims in the world. There are simply no available reliable figures about the numbers of Muslim adults per country.

34 See also Tausch, “The Fertile Grounds for ISIL Terrorism.”

35 See also Efraim Karsh, “Israel’s Arabs: Deprived or Radicalized?” Israel Affairs 19, no. 1 (2013): 2-20.

36 See Arno Tausch, Almas Heshmati, and Hichem Karoui, The Political Algebra of Global Value Change: General Models and Implications for the Muslim World (New York: Nova Science Publishers, 2015).

37 For a debate about Arab nationalism, see among others, Bassam Tibi, Arab Nationalism: Between Islam and the Nation-State (Springer, 1997). On the ideological underpinnings of such Christian radicalism, see also Samuel J. Kuruvilla, Radical Christianity in Palestine and Israel: Liberation and Theology in the Middle East. (London: I. B. Tauris, 2013).

38 Margin of error +/-12.7% at the 95% confidence level.

39 Margin of error +/-4.6% at the 95% confidence level.

40 Among the Christians in the Palestinian territories, this climate of condoning or even supporting terror against America could even be bigger and seems to amount to 46.50 percent. But with only 28 Palestinian Christians in the sample, error margins are too big for comfort and are +-18.5 percent at the 95 percent confidence level.

41 Thus, our conclusions are not too far from Daniel Pipes, “Smoking Out Islamists via Extreme Vetting,” Middle East Quarterly 24, no. 2 (2017), https://goo.gl/X3KosE.

About the Authors

Professor Russell A Berman, the Walter A. Haas Professor in the Humanities at Stanford University, is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution.

Professor Arno Tausch is a member of the Department of Political Science, Innsbruck University, and the Faculty of Economics, Corvinus University Budapest.

No comments:

Post a Comment