THE BROADBAND INDUSTRY has scored a major victory: The Federal Communications Commission just took the first step toward overturning its own Obama-era net neutrality protections.

The rules won’t disappear overnight. In a party-line vote today, the FCC formally agreed to start the process of gathering feedback before drafting a more specific plan, which could take months (#bureaucracy). But FCC chair Ajit Pai has made it clear that, barring a successful legal challenge, the agency will give up its authority to actually enforce net neutrality regulations.

The rules, first passed in 2015, ban internet service providers from blocking, slowing down, or otherwise discriminating against lawful content. Without these rules in place, your home internet provider would be free to slow down your Netflix connection to try to keep you paying for cable TV. Your mobile carrier would be allowed to block Skype in order to promote its own voice plan.

Naturally, the country’s largest broadband providers say you have nothing to worry about. In fact, the industry now claims to love net neutrality. But what the industry is calling “net neutrality” doesn’t really fit the full definition. It’s a version of net neutrality that doesn’t cover the loopholes internet providers have already discovered. If the FCC decides to drop its own protections, you probably won’t wake up one day to find YouTube or Slack blocked. But the principles that made the internet what it is today could still erode over time.

We believe in an open internet & give customers the #netneutrality protections they expect: http://comca.st/2p5waxL

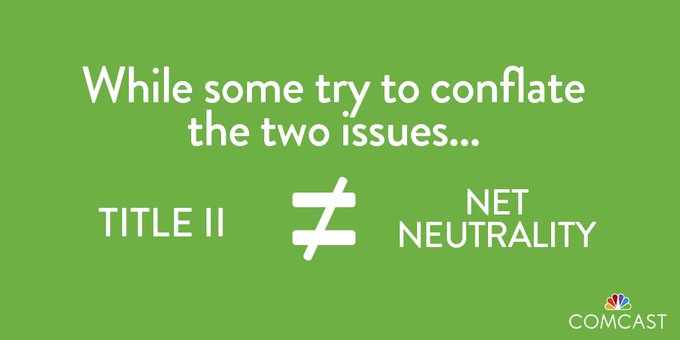

Although the telecommunications industry group US Telecom sued the FCC to try to reverse its net neutrality protections, most big internet providers say they support net neutrality in principle. Their beef, they say, is just that the FCC went too far in reclassifying broadband access as a “Title II” common carrier service, much like telephone services.

“The FCC is not talking about killing the net neutrality rules, and in fact not we or any other ISP are asking them to kill the open internet rules,” Verizon general counsel Craig Silliman said in a video the company released last month.

“Comcast supports strong, legally enforceable net neutrality protections that ensure a free and open internet for all of our customers,” Comcast executive Dave Watson wrote in a blog post.

There’s quite a bit to question in these seemingly supportive statements. Comcast, for example, sued the FCC in 2008 over Bush-era net neutrality protections adopted in 2005. In 2010, the FCC passed a new set of net neutrality protections that were more detailed than the Bush-era FCC policies. Verizon successfully sued the agency to overturn those rules in a case decided in early 2014.

But the bigger problem is that without Title II classification, the FCC won’t have the authority to actually enforce net neutrality anyway—a judgment rendered by the federal court that decided Verizon’s case against the FCC. The general consensus in the industry seems to be that Congress should pass a law banning blocking, throttling, and “paid prioritization” (so-called “fast lanes” for the internet). Executives from both AT&T and Verizon have published blog posts calling for action from Congress as well.

“We believe the best way to settle the regulatory and political ping-pong that net neutrality has become is for Congress to pass legislation that will apply to all in the internet ecosystem,” Comcast spokesperson Sena Fitzmaurice tells WIRED.

Zeroing In

An act of Congress could prevent some of the worst types of net neutrality violations. But the FCC would still lack the authority to stop internet providers from granting preferential treatment to their own services in other ways.

AT&T, for example, allows users to watch as much video as they want from its own DirecTV Live streaming service without having it count toward their data caps. Competing services like Dish’s Sling, on the other hand, will count against those caps unless the companies behind them pay AT&T to “sponsor” that data. Verizon has a similar system in place. T-Mobile exempts several streaming video and music from several different partners as part of its “Music Freedom” and “Binge On” services, but doesn’t charge companies to participate in those programs

Home broadband providers are starting to impose data limits on their customers as well. AT&T customers can use 300 gigabytes before extra fees kick in, but can avoid those extra charges if they subscribe to DirecTV. Comcast customers in 28 states have a limit of one terabyte before they’re charged extra, raising concerns that Comcast could use that limit to favor its own video services.

The principles that made the internet what it is today could still erode over time.

These data exemptions, known as “zero rating,” may sound innocent enough. Everyone loves getting free stuff. But critics argue that they will end up harming competition. While bigger players like YouTube and Netflix can probably afford to sponsor data for their customers, newer companies will be forced not only to spend extra money in order to be competitive but strike deals with every major internet provider. Companies unable to get a meeting with a provider could be effectively locked out of the market. That’s great news for established companies, but it would be bad for competition and innovation.

The FCC’s net neutrality rules didn’t outright ban these types of data exemptions, but the agency did reserve the right to intervene on a case-by-case basis. In late 2016, the FCC notified AT&T and Verizon that it believed their zero-rated services were anti-competitive. But earlier this year, in one of his first acts as FCC chair, Ajit Pai reversed that decision, signaling that the agency wouldn’t go after zero rating on his watch.

So long as internet providers are classified as Title II, a future Democrat-led FCC could step in and slap down individual zero rating schemes. If, on the other hand, internet providers are regulated under the less strict Title I classification and Congress’s rules only ban blocking and throttling, the FCC won’t have any power to regulate the practice. Nor will it have the ability to regulate any other new ways that internet providers dream up to give certain content a leg up over other content—at least not without yet another act of Congress.

In other words, the broadband industry is willing to live with a few regulations, so long as plenty of loopholes remain. On one hand, that’s progress. It’s great that the broadband industry says it supports laws regulating blocking or throttling content. But that’s not the same as supporting true net neutrality.

No comments:

Post a Comment