The Savoy, London. Eugene Kaspersky welcomes IBTimes UK to the exclusive 5-star hotel with a firm handshake. He is, as usual, just passing through, but his topic of conversation – the dark and murky work of cybercrime – has arguably never been more relevant.

For 20 years, experts from Kaspersky Lab, the Moscow-based cybersecurity firm, have fought gallantly to combat malware, spyware and viruses, often state-sponsored. Kaspersky, the firm's founder and chief executive has been on the frontlines of this cyberwar the entire time.

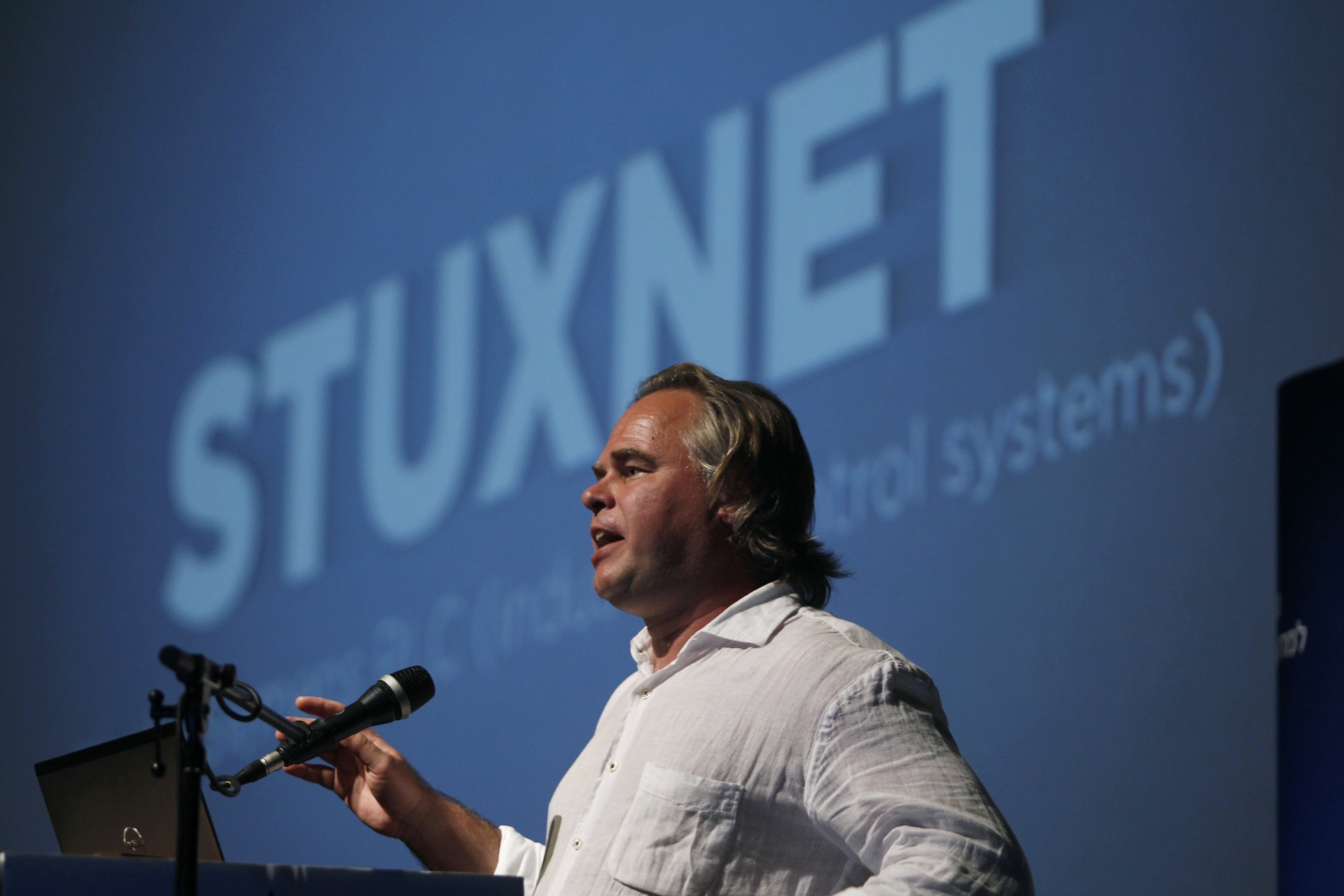

His firm helped detail the computer worm that came to be known as 'Stuxnet' – a state-sponsored creation used to destabilise Iran's nuclear ambitions. Two years ago, it exposed The Equation Group, a hacking team allegedly linked to the National Security Agency (NSA).

Kaspersky, as a result, is no longer surprised by developments in the cybersecurity industry that may appear shocking to those on the outside looking in. Only one scenario ruffles his otherwise calm demeanour: the danger posed by critical infrastructure hacking.

In 2015, Ukraine suffered a major blackout. Upon investigation, Kaspersky's Global Research and Analysis Team (GReAT) linked the attack to a strain of malwareknown as BlackEnergy.

Kaspersky has been warning about the dangers of such attacks ever since.

"Cybersecurity issues, they are with consumers, businesses, governments, government services, internet of things and industry, so now we are everywhere," Kaspersky said about his organisation, which now boasts roughly 400 million users across the globe.

Last year, a cyber-espionage and misinformation campaign against the Democratic National Committee (DNC) was officially pinned on two Russian hacking groups, codenamed Fancy Bear (APT28) and Cosy Bear (APT29). It dragged cybercrime into the mainstream.

But for Kaspersky, who is no stranger to allegations of being overly friendly with the Russian government, the world of criminality has been in a state of flux for years. It's shifting, he told IBTimes UK, to be more professional, adaptable, and as a result: lucrative.

"In the past it was relatively simple, criminals go for money and state-sponsored groups go for information," Kaspersky said. This has changed. "There is an evolution of bad guys and criminals which were much less professional in the past," he explained.

"In the last 3,4,5 years we have seen a major shift in cybercrime moving to the professional level, not all of them of course, but we see about a dozen of very highly-complicated malware families made by different groups - mostly Russian speaking."

Russia is, quite literally, a hotbed of hacking – and not all of it bad. Kaspersky stressed the useful capabilities of the country's so-called 'white-hat' coders and said that domestic software engineers are generally considered to be among the best in the world.

"We have this feedback from British companies which employ Russian engineers, Silicon Valley, Israel," he said, adding that every major city has a technical university that produces not only great computer programming experts but mathematicians.

Unfortunately, he said, hackers come from the same universities. Referencing his crime-fighting perspective on Russian Federation-based cyber-gangs, Kaspersky noted: "Countries say Russian software engineers are the best and I say Russian cybercriminals are the worst."

Exposing Russian cybercrime

Kaspersky Lab routinely works with governments to take down criminal gangs and, as a result, has a unique insight how law enforcement works to disrupt such operations. Still, its founder says the most professional cybercriminals today traditionally speak Russian.

Inside the country, the situation remains complex. Accusations have long swirled that the government employs "black-hat" hackers to do its dirty work and conduct operations in the name of national interests. When the other option is prison, it's easy to see how it works.

"There are professional gangs which have dozens of people" Kaspersky explained.

"Two years ago there was a gang inside Russia and they had an office in Moscow city.

"It was a company, they paid taxes. They had an office reception, and they were coming into the office as employees. Half of the company was legal, movie distributor – it had a license.

"But the second half of the company, they were hackers. They were really smart, they didn't attack anyone in the territory of Russia.

"And many of them they didn't have Russian passports, they didn't travel. Russian police knew about these guys for years but because there were no attacks in Russia there was no crime there so they couldn't start an official investigation [due to] the legal system."

When asked if it was possible this group had links to the nation's intelligence or security services Kaspersky said it was "technically possible".

"It's logical, it could be true – why not?" he said.

He continued: "Speaking about state sponsored attacks, I don't know what's going on in the United States, in UK, in Russia, in China and other nations but there could be contractors.

"Maybe the criminal is arrested and, like in The Matrix, is given two pills, red and blue, prison or service? I don't know, maybe. It happens with traditional criminals, they agree to assist police and work with police, and they have immunity.

"Maybe it's the same in the cyber-world, it's logical."

This entire practice was recently exposed in detail by a former Kaspersky Lab researcher, RuslanStoyanov, who is currently sitting in prison and facing mysterious charges of treason. Stoyanov has said he was detained for criticising how the state offers criminals "impunity" to hack.

Kaspersky remained coy about the ongoing situation. "I know zero about that because the investigation is going on behind closed doors. It seems it was done before his time at the company," he said, echoing a previously-released PR statement on the case.

"I didn't contact him too much, not day-by-day, but from time to time. I would say he was enthusiastic, he was really proud and there was successfully investigations. What did he do? I have no idea. There is no investigation in the company," Kaspersky added.

Welcome to the cyberwar

Amid the politics, the cyberwar rages on. From critical infrastructure cyberattacks to ransomware assaults to internet-of-things (IoT) botnets – Kaspersky has analysed it all. While he admits he has a web-connected camera, there's no sign of him going full smart-home just yet.

"Existing operating systems and applications are not secure because they are hackable," he said, yet admitted greater connectivity is clearly the future. "We cannot change that," he asserted.

Kaspersky continued: "The right way is to design better security systems for these devices. Systems must be implemented with security in mind and based on secure platforms. To develop systems based on secure platforms and design secure applications - it is possible."

Yet for now, it seems they will continue to be exploited. Only recently, one piece of malware took down large chunks of the internet in America. But where does it end? "Unfortunately until something bad happens people don't change their minds," Kaspersky warned.

Until then though, he appears unfazed by the plethora of threats that have emerged over the past 20 years since he bought the ticket and took this ride. "Typically, we can predict the next attacks," he said, adding: "Attacks on CCTVs were not surprising. Stuxnet wasn't a surprise.

"I heard about Stuxnet when I was almost ready for my August vacation. [It was] my last few days in the office and one of our experts came to me and said 'hey Eugene, you know we are waiting for something important? It happened'.

"We were waiting for something like that. Smartphone [malware], we were waiting for that for years. Every new device we [ask] can it be hacked, is there any motivation to hack this device? If there is a motivation, it will be hacked. So there are no surprises."

As global cybercrime threats continue to escalate, with cyber-espionage and major leaks of personal information now an almost daily occurrence, Kaspersky himself shows no signs of slowing.

He teased: "Right now, we are watching [a cybercrime operation]. We don't know who they are, we don't know where they are located because it's the information of the police and it's under investigation. It's about a dozen of professional gangs which are Russian speaking.

"They could be in Russia, could be in Ukraine, both maybe, or in Europe. They speak Russian and obviously have a technical background."

Most people would find that concerning. For Eugene Kaspersky, it's just another day at the office.

No comments:

Post a Comment