In the case of the so-called Islamic State (IS), Florence Gaub and Julia Lisiecka think the crime-terrorism nexus runs deep. Indeed, the organization recruits more former criminals, and funds itself more through petty – not organized – criminal activities than other groups. This tendency, however, also offers law enforcement officials an opportunity to pursue IS in a way that goes beyond the usual radicalization narrative. It does require zeroing in on hitherto neglected petty criminals, though.

That there is a link between terrorism and crime is common knowledge: terrorism itself is a crime, often funded by organised criminal activity. But in the case of Daesh, the link goes much further. The organisation recruits more former criminals, and funds itself more through petty – not organised – criminal activities than other groups. Yet this also offers law enforcement officials an opportunity to pursue it from another angle beyond the usual radicalization narrative. This requires a zeroing in on hitherto neglected petty criminals, however.

From zero to hero

European criminals are one of Daesh’s main targets for recruitment. It is estimated that between 50- 80% of Europeans in Daesh have a criminal record – substantially higher than al-Qaeda, where the same statistic stands at around 25%. The German federal police, for instance, found that two-thirds of German Daesh fighters had criminal backgrounds, one-third of whom had previously been convicted (other estimates put the number of convicted at nearly 60%). The vast majority of these were repeat offenders: 98% had committed more than one crime, and more than half had committed three or more offenses (mostly acts of violence, as well as property crimes and drug-related felonies). In fact, on average, 7.6 crimes had been committed per person. According to Belgian sources, the criminal records of jihadists mostly consist of theft and assault, and usually begin with small-scale shoplifting.

Rather than evil masterminds, Daesh recruits are therefore more often than not petty criminals: Brahim and Salah Abdeslam, two of the Paris attackers, were forced to close the bar they managed in Brussels after law enforcement officials suspected it to be a drugs den. Amedy Coulibaly, the hostagetaker at the Porte de Vincennes Kosher supermarket in Paris, had previously been jailed for handling stolen goods, drug trafficking and robbery. The el-Bakraoui brothers, who were responsible for the March 2016 attacks in Brussels, held criminal records for armed robbery, shooting at police officers (with an AK-47 no less) and attempted carjacking. Omar al-Hussein, the 22-year-old gunman who killed two people in Copenhagen in February 2015, was a member of a gang as a teenager, and was convicted for being involved in burglaries, assault, the possession of weapons and drugs; he was also jailed for a stabbing in 2013.

Continuing the trend, Mohamed Lahouaiej- Bouhlel, the driver of the lorry in the Nice attack, had been sentenced only four months prior to the atrocity to a six month suspended prison sentence for assaulting a motorist with an improvised weapon. The Berlin Christmas market attacker, Anis Amri, also had a criminal past: before arriving in Germany, he was wanted by Tunisian authorities for the theft of a truck and sentenced in absentia to five years in prison, and was also jailed in Italy for arson. More recently, the perpetrator of the attack in Westminster, Khalid Masood, was also known to the UK police due to a colourful criminal history including grievous bodily harm, possession of a knife and various public order offences.

The convergence of crime and terrorism is the result of a mutually beneficial arrangement. Daesh is interested in the skills of petty criminals as they can be of use in the preparation and execution of terrorist attacks. Many criminals have experience in avoiding authorities, are familiar with the limits of police powers, are able to act under pressure and control their emotions, often have access to weapons and illicit funds, and are used to violence. In return, Daesh legitimises the petty criminal lifestyle, and even glorifies it. In contrast to ‘judgmental’ European societies, it is perceived to offer a new and better life to those with a criminal past, absolving them of some crimes, while encouraging them to commit others. Unlike al-Qaeda, Daesh does not require a new member to possess religious knowledge, making the convergence even easier. Their recruitment slogan ‘sometimes people with the worst pasts create the best futures’ succinctly captures this approach.

In some cases, it is the inherent risks of the criminal underworld that make Daesh attractive for petty criminals. Reda Nidalha, a Dutch teenager of Moroccan descent, left for Syria after he was subjected to extortion by his former criminal associates, who claimed he owed them money. One Moroccan-born Belgian recruiter, Khalid Zerkani, targeted (and recruited) 72 young Belgians with migrant backgrounds, most of whom had a history of petty criminality. He did this by bestowing religious legitimacy on their actions, arguing that ‘to steal from the infidels is permitted by Allah’ and necessary to finance travel to ‘zones of jihad’. Daesh itself is, of course, a criminalising element as it encourages all its supporters (even those without previous criminal records) to involve themselves in criminal activities. In one such case, eight Daesh supporters in Germany were prosecuted for stealing from a number of churches, shops and schools, generating around €19,000 for the organisation.

Yet while crime usually precedes radicalisation, the two tend to mutually reinforce each other. In general, the interplay of crime and terrorism therefore shortens the time between radicalisation and action.

The prison: jihadist accelerator?

Although most people are recruited outside of prison, incarceration can play an important role in the transformation from petty criminal to jihadist. But while around two-thirds of Daesh supporters with a criminal past have served some form of sentence, only 27% said that they were radicalised while incarcerated, according to the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR).

In these cases, prison can act as an incubator for jihadists since it facilitates the creation of networks between petty criminals and jihadist ideologues, as well as the formation of likeminded cells. The poor conditions in some prisons, as well as the prospects of a difficult restart following release can foster an environment conducive to networking. The Charlie Hebdo attacker Cherif Kouachi met Amedy Coulibaly in Europe’s largest prison, Fleury- Mérogis, and both were mentored there by Djamel Baghdal, an al-Qaeda recruiter. The group continued to meet after they were released from prison and were involved in a jailbreak of another jihadist prisoner. Coulibaly himself stated that “prison is the best fucking school of crime. In the same walk, you can meet Corsicans, Basques, Muslims, robbers, small-time drug dealers, big traffickers, murderers… you learn from years of experience”.

Across the Rhine, Harry Sarfo, a German Daesh sympathiser was radicalised during his stay in a Bremen jail after he was involved in an armed robbery of a supermarket. In prison he met René Marc Sepac, a known figure in Germany’s Salafist scene and a facilitator of travel to Syria. After leaving prison, Harry departed for Syria and was trained there, yet decided to return to Germany where he convinced the judge that he had been an innocent bystander. An execution video released shortly after he was convicted for three years (which showed him pointing a gun at the head of the victim), proved that this was indeed not the case.

Although life in prison does play a radicalising role for a portion on their path to jihadism, cause and effect should not be confused: the transgression of societal norms and laws that precedes sentencing is already the first step towards radicalisation.

Criminal money for criminal acts

One of Daesh’s main motivations for targeting petty criminals is its need for large amounts of funds which can be quickly generated under the radar of law enforcement agencies. This is where organised crime networks differ from terrorist groups: whereas the former generate illicit income simply to this end, the latter need it to engage in numerous offshoot activities, ranging from recruitment and travel to the acquisition of weapons and explosives. While their interests therefore overlap, their motivations usually do not. This does not, however, prevent collaboration: in April last year, Franco Roberti, Italy’s national anti-terror and anti-mafia chief, confirmed that the mafia and Daesh had colluded in the smuggling of cannabis into Europe from Libya.

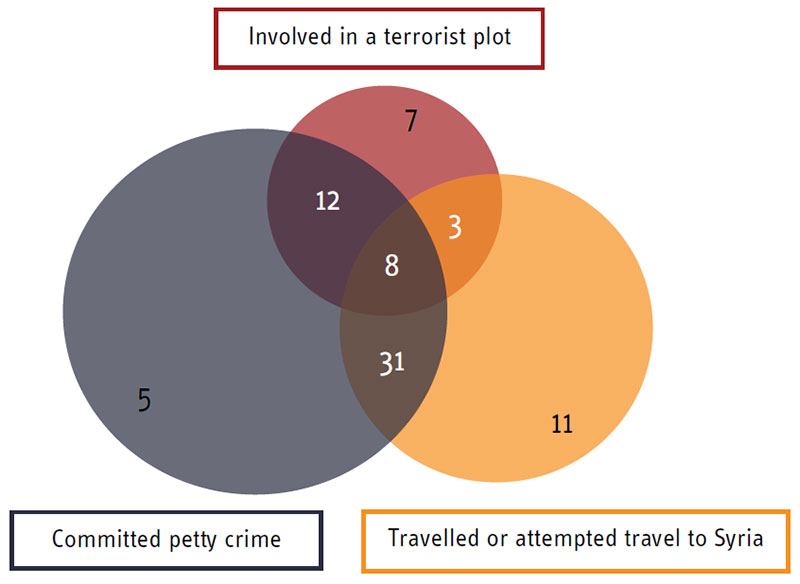

A sample of European jihadists with a criminal past, post-2011*

Data source: International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR). *Total number = 77

Of course, Daesh did not invent this type of financing: the Taliban relied on income from heroin production, al-Qaeda recommended credit card fraud, and the 2004 Madrid attackers had financed their activities with drugs and arms sales. But the group took this manner of generating funds to new levels, both in Europe and abroad. In Iraq, it funded itself mainly through kidnappings, extortions, car thefts and the drug trade before it moved into the smuggling of oil. Even today, the narcotics trade accounts for 7% of the organisation’s overall income.

In Europe, its activities are funded mostly through petty crime: more than half of funds for terrorist attacks in Europe, as well as for travel to Syria and Iraq have been generated through drug-dealing, theft, robbery, the sale of counterfeit goods, loan fraud, and burglary. The weapons used during the Charlie Hebdo attacks, for instance, were acquired using money made by Said Kouachi from selling counterfeit trainers. Mohamed Merah, who killed seven people in Toulouse in 2012, funded his attack from bank robberies and break-ins. VAT and business fraud are other highly lucrative sources of financing: a Swedish Salafi preacher funded activities of terror cells through ‘missing trades’ worth over €60,000 until he was caught by security services in 2013.

Loans which are not paid back, the failure to return rental vehicles, as well as social insurance fraud are also handy revenue streams. Amedy Coulibaly, together with his wife, raised significant sums for his attack by taking out two consumer loans using a fraudulent payslip from a fake company (which had no employees registered). Using this method they were able to acquire €33,000, some of which was used to buy a car, which was later exchanged for weapons.

Petty crime is attractive to terrorists for two reasons. First, while its revenues are modest, it does not have to generate as much as organised crime because terrorist attacks are comparatively cheap: 76% of terror plots in Europe between 1993 and 2013 cost less than $10,000. The Paris attacks in November 2015 likely cost less than €30,000 (including the cost of training in Yemen) – around the same as a purchase of a new mid-range car. Second, petty crime provides a source of income which has a good chance of remaining undetected by law enforcement agencies. Consequently, terrorist cells which self-finance in this manner (rather than receiving funds from abroad) are more successful in carrying out attacks because they are less likely to be detected by security services.

Whether procuring fraudulent travel documents, weapons, getaway cars, unregistered mobile phones, safe houses or bomb-making materials, petty criminals often have the necessary knowledge to facilitate or conduct terrorist attacks. The Verviers cell responsible for the attacks in Paris and Brussels, for instance, used their connections with the criminal underworld to obtain fake documents. Copenhagen attacker Omar al-Hussein acquired the gun for his first attack during a home robbery, and another firearm on the day of the second attack through contacts with former gang members. Amedy Coulibaly similarly bought his weapons through an underground contact who allegedly did not know they were to be used in a terrorist attack.

Petty crimes not only fund terrorist attacks, but also pay for travel to Daesh-held territory. In the UK, for instance, jihadists have funded their trips with student loans and ‘payday loans’ (short-term loans with high interest rates), which are more easily obtained compared to other European countries. This type of fraud is more commonly linked to traveling because it generates a high amount in a comparatively short time – the profiles of foreign fighters show that the period between the decision to travel and the actual act is usually only a few weeks.

The ‘Al Capone’ approach

Yet the strong link between Daesh and petty crime also provides an opportunity for law enforcement to catch terrorists by other means – much akin to how notorious US gangster Al Capone was finally jailed for tax evasion rather than murder and organised crime.

This insight has not yet penetrated all circles working on counter-terrorism, and while the United Nations Security Council, for instance, recognises the link between organised crime and terrorism, there is very little attention paid to petty crime. At the national level, different law enforcement agencies are usually tasked to combat both phenomena, leading to jihadists falling through the cracks. For example, French customs police filed a report with the country’s domestic intelligence service requesting support after it discovered the counterfeiting operations of the Kouachi brothers, but the request was not followed up.

Linking criminal activities to terrorist charges is also challenging as the former are much more frequent than the latter. Every year, the average European country records nearly 300 assaults and more than 500 burglaries – recognising the links between some of these and terrorist activities is a tall order.

Sharing information across agencies is, as always, a good start. But legal changes could help, too. Petty criminals successfully prosecuted with assisting terrorists have usually not been charged with terrorism but with other crimes. Djamal Eddine Ouali, who managed a ‘forgery factory’ in his flat, provided documents to several of the Paris attackers – but he was charged only with ‘participation in a criminal organisation’ and ‘falsification of documents’, since he claimed not to have known about his clients’ intentions. Sentences for petty crimes are considerably lower than those for terrorism charges; they could either be increased, or collusion with terrorists could be met with tougher sentences.

Decriminalising certain acts could equally dry up some sources of income for both terrorists and organised crime. In Italy, Franco Roberti has called for the decriminalisation of cannabis, or even its legalisation, to hit the coffers of both Daesh and the mafia. Another way to reduce their sources of income is the improvement of mechanisms which alert authorities to multiple loan applications (especially those with no guarantees) or VAT fraud (especially linked to IT or mobile phone sales), as well as the fraudulent leasing of cars. Even the toughening of traffic law could be a way to curtail terrorist activity; after all, there is the possibilty that the Nice attack could have been prevented (or could have caused less damage) if the police had enforced the ban on heavy vehicles in the town centre at the time of the event.

More generally, an enhanced fight against both petty and organised crime will inadvertently also help to drain the pool of members and new recruits. While prisons alone appear to have little impact on the deterrence of criminal behaviour, they incapacitate offenders simply by incarceration. Focusing on the prevention of juvenile delinquency might assist to some extent, but its impacts will be felt only in the medium term. More immediate action is therefore required.

About the Authors

Florence Gaub is a Senior Analyst and Julia Lisiecka a Junior Analyst at the European Union Institute of Security Studies (EUISS).

No comments:

Post a Comment