BRAHMA CHELLANEY

Russia may be in decline economically and demographically, but, in strategic terms, it is a resurgent power, pursuing a major military rearmament program that will enable it to continue expanding its global influence. One of the Kremlin’s latest geostrategic targets is Afghanistan, where the United States remains embroiled in the longest war in its history.

Russia may be in decline economically and demographically, but, in strategic terms, it is a resurgent power, pursuing a major military rearmament program that will enable it to continue expanding its global influence. One of the Kremlin’s latest geostrategic targets is Afghanistan, where the United States remains embroiled in the longest war in its history.

Almost three decades after the end of the Soviet Union’s own war in Afghanistan – a war that enfeebled the Soviet economy and undermined the communist state – Russia has moved to establish itself as a central actor in Afghan affairs. And the Kremlin has surprised many by embracing the Afghan Taliban. Russia had long viewed the thuggish force created by Pakistan’s rogue Inter-Services Intelligence agency as a major terrorist threat. In 2009-2015, Russia served as a critical supply route for US-led forces fighting the Taliban in Afghanistan; it even contributed military helicopters to the effort.

Russia’s reversal on the Afghan Taliban reflects a larger strategy linked to its clash with the US and its European allies – a clash that has intensified considerably since Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea spurred the US and Europe to impose heavy economic sanctions. In fact, in a sense, Russia is exchanging roles with the US in Afghanistan.

In the 1980s, US President Ronald Reagan used Islam as an ideological tool to spur armed resistance to the Soviet occupation. Reasoning that the enemy of their enemy was their friend, the CIA trained and armed thousands of Afghan mujahedeen – the jihadist force from which al-Qaeda and later the Taliban evolved.

Today, Russia is using the same logic to justify its cooperation with the Afghan Taliban, which it wants to keep fighting the unstable US-backed government in Kabul. And the Taliban, which has acknowledged that it shares Russia’s enmity with the US, will take whatever help it can get to expel the Americans.

Russian President Vladimir Putin hopes to impose significant costs on the US for its decision to maintain military bases in Afghanistan to project power in Central and Southwest Asia. As part of its 2014 security agreement with the Afghan government, it has secured long-term access to at least nine bases to keep tabs on nearby countries, including Russia, which, according to Putin’s special envoy on Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov, “will never tolerate this.”

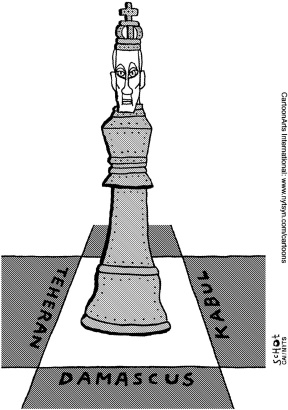

More broadly, Putin wants to expand the geopolitical chessboard, in the hope that he can gain sufficient leverage over the US and NATO to wrest concessions on stifling economic sanctions. Putin believes that, by becoming a major player in Afghanistan, Russia can ensure that America needs its help to extricate itself from the war there. This strategy aligns seamlessly with Putin’s approach in Syria, where Russia has already made itself a vital partner in any effort to root out the Islamic State (ISIS).

In cozying up to the Taliban, Putin is sending the message that Russia could destabilize the Afghan government in the same way the US, by aiding Syrian rebels, has undermined Bashar al-Assad’s Russian-backed regime. Already, the Kremlin has implicitly warned that supply of Western anti-aircraft weapons to Syrian rebels would compel Russia to arm the Taliban with similar capabilities. That could be a game changer in Afghanistan, where the Taliban now holds more territory than at any time since it was ousted from power in 2001.

Russia is involving more countries in its strategic game. Beyond holding a series of direct meetings with the Afghan Taliban, Russia has hosted three rounds of trilateral Afghanistan-related discussions with Pakistan and China in Moscow. A coalition to help the Afghan Taliban, comprising those three countries and Iran, is emerging.

General John Nicholson, the US military commander in Afghanistan, seeking the deployment of several thousand additional American troops, recently warned of the growing “malign influence” of Russia and other powers in the country. Over the past year, Nicholson told the US Senate Armed Services Committee, Russia has been “overtly lending legitimacy to the Taliban to undermine NATO efforts and bolster belligerents using the false narrative that only the Taliban are fighting [ISIS].”

The reality, Nicholson suggested, is that Russia’s excuse for establishing intelligence-sharing arrangements with the Taliban is somewhat flimsy. US-led raids and airstrikes have helped to contain ISIS fighters within Afghanistan. In any case, those fighters have little connection to the Syria-headquartered group. The Afghan ISIS comprises mainly Pakistani and Uzbek extremists who “rebranded” themselves and seized territory along the Pakistan border.

In some ways, it was the US itself that opened the way for Russia’s Afghan strategy. President Barack Obama, in his attempt to reach a peace deal with the Taliban, allowed it to establish a de facto diplomatic mission in Qatar and then traded five senior Taliban leaders who had been imprisoned at Guantánamo Bay for a captured US Army sergeant. In doing so, he bestowed legitimacy on a terrorist organization that enforces medieval practices in the areas under its control.

The US has also refused to eliminate militarily the Taliban sanctuaries in Pakistan, even though, as Nicholson admitted, “[i]t is very difficult to succeed on the battlefield when your enemy enjoys external support and safe haven.” On the contrary, Pakistan remains one of the world’s largest recipients of US aid. Add to that the Taliban’s conspicuous exclusion from the US list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations, and it is difficult for the US credibly to condemn Russia’s overtures to the Taliban and ties with Pakistan.

The US military’s objective of compelling the Taliban to sue for “reconciliation” was always going to be difficult to achieve. Now that Russia has revived the “Great Game” in Afghanistan, it may be impossible.

No comments:

Post a Comment