“Bombard the Headquarters” — China and the Liberal Order

What to read ahead of the Xi-Trump summit

Typically, the visit of a Chinese leader to the United States provides the stage for analysts to reflect on the effectiveness of U.S. efforts to defend the liberal international order against China’s challenge.

Not this time.

With the Trump administration weakening its commitments to crucial pillars of the liberal order, and in some areas even threatening to overturn them, the lead-up to Xi Jinping’s Florida trip has elicited commentary of a different flavor. As François Godement notes in a recent report for ECFR:

The election of Trump and the rise of populist and anti-globalization forces in the West might signal a paradigm shift on the issue of China and the global order. Just two or three years ago, questions about the future of the global order centered on China’s potential contributions or challenges to it. Today, the world finds itself asking whether China could step in to lead, and what that would mean.

Most of the analysis by leading China hands around Xi Jinping’s Swiss outing in January, when his Davos and Geneva speeches placed the question of China’s leadership role firmly on the table, was scathing. One elegantly excoriating take by Liz Economy on China’s credentials as a “champion of globalization” concludes with the warning that:

Global leadership has to be earned on merit, not simply granted in desperation and hope. The world must recognize that globalization with Chinese characteristics is not globalization at all.

Yet Xi’s achievement — and Trump’s failure — has been in the reframing of the debate.

Last year there was an emerging consensus among Western policymakers not only that Chinese behavior in an assortment of trade and economic fields was undermining confidence in the global economic system, but that an exceptional response was required. Economists and businesspeople who once physically recoiled every time they heard the word “reciprocity ” were reluctantly becoming its advocates when it came to dealing with China.

The Trump administration has achieved the implausible feat of making the United States appear the greater potential threat to the open global trade order than China — at least temporarily.

Some analysts even pinned the big illiberal upsets of 2016 on Chinese trade practices. A series of papers by Autor, Dorn and Hanson looked at the impact of the “China shock” on the U.S. presidential election and the ideological composition of the House of Representatives, methodology that was replicated by Colantone and Stanig in their analysis of its role in the Brexit vote. The conclusion in each case: the Chinese import surge had a crucial part to play in tipping the balance of public opinion. But with all of the Trump administration’s talk of “economic nationalism”, outright protectionism, withdrawal from TPP, and threats to the WTO, it has achieved the implausible feat of making the United States appear the greater potential threat to the open global trade order than China — at least temporarily.

Clearly no-one is being fooled into thinking that China has transmogrified into a paragon of anti-protectionist virtue. An op-ed by the German ambassador to Beijing captures the current tone — taking advantage of Xi’s “pro-globalization” language to push China on its commitments, while continuing to note the many aspects of Chinese behavior that are wildly inconsistent with this stance. But it gloomily notes that while “the future of US policy is unclear…it would be a huge surprise to see it morph into a champion of multilateralism” and as a result, “Germany, as well as the EU, is ready to intensify cooperation with China in order to keep globalization going”.

The Economist’s visit preview, in unpacking the new terms of art that followed Xi’s speeches — the “two guides” and the “China solution” — explains why China suddenly looks so appealing, despite the obvious caveats:

China is a revisionist power, wanting to expand influence within the system. It is neither a revolutionary power bent on overthrowing things, nor a usurper, intent on grabbing global control.

In normal conditions, elements of that revisionism are a profound concern. During a period of populist insurgencies and deep uncertainty about the direction of US foreign policy, it is the fact that China is not a “revolutionary power” that becomes more salient. This is an argument I explore in more detail in previous piece for Out of Order, the “Great Powers and the Counter-Enlightenment”.

Beijing has an opening to consolidate a strengthened position for itself in the global order.

If the Trump administration’s foreign and economic policy takes on a more predictable and traditional quality, that would almost certainly shift, but with nervous U.S. friends and allies discreetly hedging their bets, it is clear that Beijing has an opening to consolidate a strengthened position for itself in the global order. In the past, China has not always been very adept at taking advantage of these opportunities. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, for instance, instead of consolidating a reputation as a new pillar of the global system, Beijing’s hubristic and assertive behavior magnified the sense among many actors that it was a growing threat. This time, in fields ranging from trade to climate to the UN, China is playing its hand more effectively.

One area in which China would still expect to find itself on the wrong side of a dividing line from the United States and its like-minded allies is democracy and human rights. Ahead of the Xi visit, however, the Trump administration has abdicated the traditional U.S. position on these issues too. Its unwillingness to sign on to a recent letter from embassies in Beijing, over claims that lawyers and human rights activists were tortured in detention, was another striking illustration.

A couple of visit previews contend that this decoupling of liberalism from U.S. China policy may have benign consequences. Orville Schell argues, in his article on China’s democratic legacy, that:

Paradoxically, with the new U.S. president seemingly disinclined to exert public pressure on Beijing about democracy and the rule of law, the Chinese themselves may be better able to find their own voice on these issues.

This is explored further in a piece by Taisu Zhang, which contends that “if a Trump presidency takes ‘liberalism’ out of the perceived ‘West,’ then it is not inconceivable that there can be some room for intellectual reconciliation between Chinese nationalism and liberalism.”

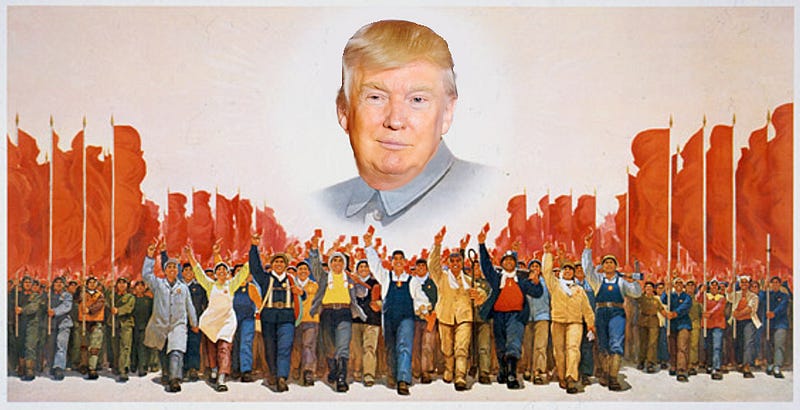

That seems overly optimistic given the Communist Party-sized obstacle to a rebirth of Chinese liberalism. But it is illustrative of an unusual degree of flux in the ideological terrain that is leaving many people uncertain whose side they are on. A particularly vivid exploration of these issues comes in Chris Buckley’s look at how the neo-Maoists in China are navigating the new world of Trump, populism, and a Chinese leader seeking to grab the pro-globalization mantle:

Some Maoists say Mr. Trump also offers a model. They think he led a populist revolt that humbled a corrupt political establishment not unlike what they see in China. They cheer his incendiary tactics, sometimes likening them to Mao’s methods. And they hear in his remarks an echo of their own disgust with Western democracy, American interventionism and liberal political values…

…Many Maoists see Mr. Xi as a fellow traveler who is taking China in the right direction by restoring respect for Mao and Marx. But others say privately that even Mr. Xi may not be a dependable ally. They point out that he has promoted himself abroad as a proponent of expanding global trade and a friend of multinational corporations, drawing an implicit contrast with Mr. Trump.

CNN takes the Mao comparison further, interviewing analysts who see a “silver lining in Trump’s ‘Maoist’ mentality”:

For too long, they argue, the Communist leadership in Beijing has been taking advantage of successive administrations in Washington — benefiting from an open global trade system advocated by the U.S., and then using its rising economic might to reinforce an authoritarian political system at home and fund its strategic expansion abroad… “Trump may be …illogical or clueless about politics, but he knows that things have to change — and the only way to do so is through unconventional means. As he turns the world upside down, China must feel nervous.”

But U.S. friends and allies feel nervous too. And if the strange role reversal between the United States and China on their commitment to the maintenance of critical pillars of a stable global order persists, Beijing may face a new set of burdens but it is also poised to reap many of the political rewards.

No comments:

Post a Comment