Yossi Alpher

Israel’s next big war is almost certainly going to pit it against some combination of Iranian, Syrian and Hezbollah forces along its northern borders with Syria and Lebanon. To be sure, an additional confrontation with Hamas in Gaza (Israel’s opponent in the costly 2014 Gaza War. which led to the death of roughly 2,100 Palestinians and 73 Israelis) could also be in the offing. But the forthcoming war in Israel’s North — home to an estimated 1.2 million people — could be closer to the kind of all-out war that the Jewish state hasn’t fought since 1973.

Israel’s next big war is almost certainly going to pit it against some combination of Iranian, Syrian and Hezbollah forces along its northern borders with Syria and Lebanon. To be sure, an additional confrontation with Hamas in Gaza (Israel’s opponent in the costly 2014 Gaza War. which led to the death of roughly 2,100 Palestinians and 73 Israelis) could also be in the offing. But the forthcoming war in Israel’s North — home to an estimated 1.2 million people — could be closer to the kind of all-out war that the Jewish state hasn’t fought since 1973.

The reasons have far less to do with the Arab-Israel conflict than with the ongoing civil war in Syria and the continuing confrontation between Iran and Israel. The outcome could result in considerable destruction inside Israel, but also in a strengthening of Israel’s burgeoning strategic ties with its Sunni neighbors — Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — who alongside their reservations on the Palestinian issue share Israel’s concerns regarding Iran’s aggressive regional ambitions. In this sense, a confrontation in Israel’s north would decisively reflect current far-reaching changes in the Middle East strategic balance of power.

Syria’s civil war is winding down, at least in the Western or non-desert part of Syria facing the Mediterranean — appropriately termed “Useful Syria” — and in the South, along Syria’s borders with the Israeli Golan Heights and Jordan. Iranian and Russian intervention has turned the tide in favor of the Assad regime in Damascus. In helping Bashar al-Assad to win on the ground, Tehran has mustered a broad war coalition of Shiite mercenaries from as near as southern Lebanon’s Hezbollah and as far afield as Afghanistan and Iraq. The end of fighting in Useful Syria is liable to leave all these battle-tested forces near the Golan. Alongside them will be al-Assad’s ally, Hezbollah, with its estimated arsenal of close to 100,000 rockets and missiles capable of targeting most of Israel, as far south as the Dimona nuclear reactor.

True, Iran’s proxy army, as well as Hezbollah, suffered losses in Syria and is battle weary. But Iran now has the financial resources to speed its return to battle-readiness. This force is understood by Israeli military intelligence to represent the primary military threat to the country for several reasons. First, both Iran and Hezbollah continue to issue a barrage of threats against Israel — hardly the pose of someone shying away from a fight. In February, Iranian Supreme Leader Sayyid Ali Hosseini Khamenei, pictured above, referred to Israel as “a cancerous tumor that should be cut and will be cut.”

Second, victory in Syria will represent a major Iranian strategic success in projecting its power in the region. Iran, which is zealously buying top-flight weapons from Russia, is trying to develop a Mediterranean naval presence as well, with a port on the Syrian coast.

Third, a combination of Syrian, Iranian and Hezbollah pressure has spurred a political shift in Lebanon. President Michel Aoun, a Christian who owes his recent election to Hezbollah support, stated on February 12 that Hezbollah’s weapons are complementary to those of the Lebanese army: “The resistance’s [meaning Hezbollah’s] arms are … an essential part of Lebanon’s defense.”

This groundbreaking and, inside Lebanon, controversial statement abrogates Lebanese policy that once proclaimed that only the Lebanese army defends the country. Lebanon used to at least project a certain distance between Hezbollah’s strategic aims and activities and those of sovereign Lebanon. Already there are signs that the Lebanese army in southern Lebanon is deferring to Hezbollah forces along Israel’s border. Given the between the Lebanese military and Hezbollah’s forces, Israel is justified in deeming another attack by Hezbollah an act of war by Lebanon itself and responding militarily against the Lebanese army and the country’s infrastructure. Yet this could have a devastating effect on both Lebanon’s delicate internal ethnic equilibrium and Israel’s otherwise improving relations with the Arab world.

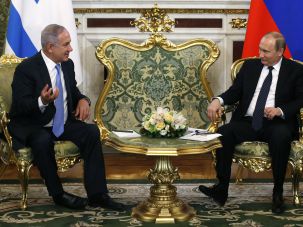

On March 9, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu traveled to Moscow for a summit with Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, for the fourth time in the past 18 months. Since Russian forces entered Syria in September 2015 to rescue the Assad regime, Jerusalem and Moscow have had much to talk about, including ways to ensure that Israeli and Russian combat aircraft don’t get into dogfights in the skies over Damascus. Changed global strategic circumstances may also now dictate that Netanyahu exploit his close contacts with both Putin and President Trump to pass messages between the two. But Netanyahu very pointedly stated after his meeting that the main agenda item was Iran: not the Iran nuclear deal, which is a fait accompli, but the growing Iranian military threat to Israel from Syria and Lebanon.

These developments raise weighty questions. Can Putin be persuaded to escort Iran’s forces and proxies out of Syria as part of the Russian endgame there? Will the Israeli threat to target all of Lebanon next time around succeed in deterring another war with Hezbollah, or could it have the unfortunate effect of widening that war? And if war breaks out and Hezbollah rains tens of thousands of missiles over most of Israel, will an all-out Israeli response that targets large portions of both Syria and Lebanon succeed in ending the next war quickly? Will Iranian forces suffer enough damage in the fighting to deter Tehran in the future? Will Israel, too, suffer heavy civilian and infrastructure damage?

Last but not least, where does the Trump administration weigh in regarding the increasing Iranian threat to Israel from Syrian and Lebanese soil? The United States and Russia are potentially the only parties capable of changing the reality on the ground in Syria. The Arab world certainly won’t.

No comments:

Post a Comment