Anirudh Kanisetti

India has a tradition of pluralism and tolerance that makes us uniquely suited to a role of global leadership in a multipolar world.

India has a tradition of pluralism and tolerance that makes us uniquely suited to a role of global leadership in a multipolar world.

In1805, the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte conquered most of Germany, overthrowing the smaller princedoms and humbling the Prussians and Austrians. This led to Germans beginning to see themselves, for possibly the first time, as possessing a broader loyalty than their direct rulers: as being “Germans” (especially as being anti-French). It was a mature form of the same sentiment that Otto Von Bismarck, Chancellor of Prussia, took advantage of in 1870 to defeat France and unite Germany into the Second Reich, in a swell of nationalistic fervour.

The Proclamation of the German Empire in 1870. Bismarck is at the centre, dressed in white. German nationalism was one of the great shaping forces of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

As the 19th century drew to a close, Europe continued to modernize. Old feudal ties had been swept away by centralizing empires such as Austria and Russia. Yet the modernizing imperial project offered little to subject peoples who weren’t part of the ruling culture or linguistic group. Hungarians in Austria-Hungary, for example, demanded not only the right to self-rule but also respect for their culture and traditions, as did the Polish in Tsarist Russia[1]. Virulent forms of nationalism, in fact, later led to the rise of Fascism and Nazism and were certainly responsible for the Second World War. After the World Wars, national boundaries based on regional cultures and linguistic histories did indeed seem to be the firmest basis for states which could offer no other common ties to their voting citizenry. Radical nationalism, it was thought, was a thing of the past.

(Of course, in their wisdom, the colonial empires did not see fit to extend that principle to Africa and the Middle East, causing endless sub-national strife.. But that’s a story for another day.)

The European Union. What are the odds that a continent torn by centuries of strife would even form some sort of union?

The European Union. What are the odds that a continent torn by centuries of strife would even form some sort of union?

Over the course of the 20th century, the capitalist global order began possibly the greatest improvement in living standards yet seen in human history. This seemed to bode well for enthusiasts of grander projects such as the European Union. Nationalism in Europe, a continent that had suffered through two brutal world wars, had harnessed unifying sentiments in each nation that allowed for rapid development, and seemed to now give way to a greater ideal — pan-Europeanism. Eventually, some argued, we’d no longer need national boundaries. We’d all be global citizens, free to take part in the great experience of humanism.

But this great project didn’t last. Over the last decade, the mistakes of the West have come back to haunt the international system, what with militant jihadism, the 2008 collapse of the banking system, and essentially pointless wars in the Middle East that have served to drive the region further and further into anarchy. The response has broadly been one of fear and withdrawal, with right-wing nationalists with slogans like “America First” being voted into power on the basis of the idea that their nation alone is supreme, that their nation’s interests are the most important.

India has not been an exception. In 2014, the Indian electorate delivered an overwhelming mandate to the BJP, with a massive majority in Parliament as well as successive state elections. Yet what exactly the mandate was for is still in question. The BJP/RSS believe it was for a developed Hindu Rashtra. Other commentators believe it was anti-incumbency and deep disillusionment with scams and slow economic growth.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party has rarely hid its Hindutva credentials. In this photo, he gives a speech from the Mughal Red Fort, with the Jama Masjid mosque in the background. Ironically, these are both icons of Indo-Islamic art.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party has rarely hid its Hindutva credentials. In this photo, he gives a speech from the Mughal Red Fort, with the Jama Masjid mosque in the background. Ironically, these are both icons of Indo-Islamic art.

If the 2017 UP elections are any indication, it looks like the BJP was a little off in its understanding of the electorate. Development and economic growth are on top of the voters’ demands: Hindutva, nationalism, and sacrifice for the nation (as the BJP attempted to brand demonetization) are not working as expected. This should not be a surprise, considering that nationalism itself is an idea that’s nearly 200 years out of date. In a world of repressive empires, in relatively homogeneous linguistic and cultural groups, it had worked wonders.

But India isn’t Europe: and what worked in Europe in 1870 isn’t going to work in India in 2017. For that matter, it’s clearly not working for the world in the 21st century (just look at President Trump’s approval ratings on his first day in office — and the popular and judicial opposition to his alt-right supporters and executive orders.)

India, the country, is about the size of Western Europe. It’s far more populous (Many Indian states have populations larger than those of entire countries). It’s far more diverse, culturally, religiously, and linguistically.

To paraphrase Gibbon: Rather than ask why nationalism isn’t working in India, we should instead be asking why it has survived so long.

So let’s stop looking at India from a Western lens and better understand the history and traditions of the subcontinent.

Gandhara-style Buddha, 1st-2nd century CE. The Gandhara school of art is an elegant fusion of Indian and Hellenic styles,.

Gandhara-style Buddha, 1st-2nd century CE. The Gandhara school of art is an elegant fusion of Indian and Hellenic styles,.

Monolithic ideologies don’t work in India. Whether it was the Indo-Greek kings or the Mughal Emperors, India’s rulers have always voluntarily or involuntarily been tolerant of the diversity of the subcontinent. India learned from and taught the world. From the Gandhara school of art and Nalanda University to Sufi Islam and Indo-Islamic architecture[3], for thousands of years, the subcontinent has cared little for discrimination on the basis of anything (except caste. That’s something we need to answer for.) In the courts of the Mughals, religion didn’t matter. Where you were from didn’t matter: merit was the most important factor [4]. As the Empire declined, this culture was broadly absorbed by the Indo-Islamic aristocracy. Urdu culture and poetry praised the god Rama as the Imam of Hindustan and Awadh as the birthplace of Muhammad[5]; all this tangible pluralism we have forgotten while politicians peddle inflammatory mischief about temple destruction and rape which isn’t even borne out by historical sources.

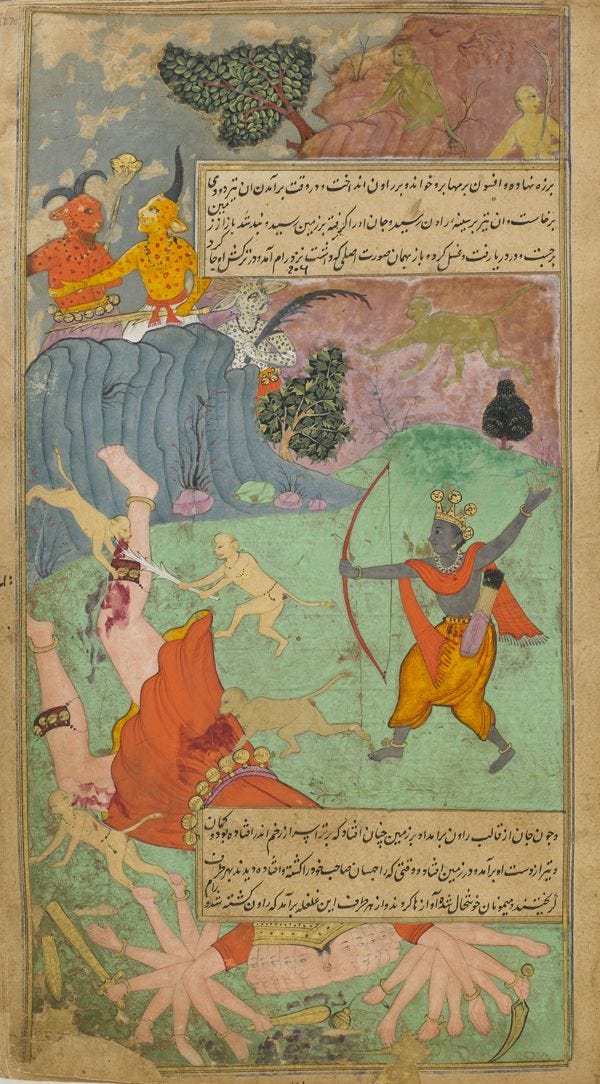

The god Rama slays the demon Ravana. Mughal miniature, displaying elements of Persian and Indian painting traditions.

The god Rama slays the demon Ravana. Mughal miniature, displaying elements of Persian and Indian painting traditions.

Pluralism is an established and long-standing tradition.There is nothing that we can put into a neat little bucket and call “Indian”. Temple architecture, sculpture, and religious practices reflect thousands of years of cultural accommodation[2][3]. Trying to impose a simplistic form of nationalism — whether it’s based on Hindi or on religion- is a perversion of this grand tradition. No wonder, then, that Hindu nationalism is already getting old, just as Aurangzeb’s Islamic orthodoxy was almost immediately repudiated by his subjects and successors. Peace and prosperity are more important than the glory of God — now more than ever.

What do we need to change?India’s sense of historical consciousness has been shaky at best, since colonial times. People need to know more about the subcontinent’s heritage and tolerance. The message that political parties and school textbooks need to convey is not one of division and exclusion but inclusion and development. None of these are easy to achieve. But think about it this way: in a world that’s increasingly terrified, inward-looking, and uncertain, what greater goal can there be than to lead by an example, and prove that narrow identities don’t matter?

Going by history, what other nation is suited to a role such as this? India is the land of tolerance. India is the land of pluralism. If we’re able to develop a national narrative where religion, caste, and language are irrelevant, we’ll be able to harness demographic forces that have never existed in human history: a massive, young population, yearning for economic growth, and tired of division. We are at a crossroads in the story of India. But we are also at a crossroads in global history.

This is the world of Brexit. This is the world of Trump. This is the world where Partition happened. But we can learn from our mistakes. More than any other country, India has a history and tradition of pluralism and tolerance that makes us uniquely suited to a role of global leadership in a multipolar world. It’s time that we stepped up to the mantle that the US has abdicated: don’t look to China to lead the world now. We can and must take the podium. It’s time for India, once again, to be a Great Power.

Anirudh Kanisetti was a student of Takshashila’s Graduate Certificate in Public Policy programme in 2016.

Bibliography:

Thomson, David. Europe Since Napoleon. London: Longmans, 1962.

Thapar, Romila. The Penguin history of early India: from the origins to AD 1300. Penguin UK, 2015.

Basham, Arthur Llewellyn, and Saiyid Athar Abbas Rizvi. The wonder that was India. Sidgwick and Jackson, 1956.

Eraly, Abraham. The Mughal World: Life in India’s Last Golden Age. Penguin Books India, 2007.

Naqvi, Saeed. Being the Other: The Muslim in India. Aleph Book Company, 2016.

Hamilton, Nigel. American Caesars: Lives of the US Presidents, from Franklin D. Roosevelt to George W. Bush. Random House, 2011.

No comments:

Post a Comment