Robert Beckhusen

The first of 3,500 American troops began rolling into Poland for a nine-month-long mission starting on Jan. 8, 2017. It’s an unprecedented length of time for a U.S. armored unit to stay in Eastern Europe. The U.S. Army’s 3rd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division were heading to Zagan and Pomorskie, with the unit’s 87 M-1 Abrams tanks following on trains.

It’s the beginning of a bulked-up and continuous NATO troop rotation to counter a resurgent Russia. In addition to the tanks, the unit is bringing with it 18 self-propelled Paladin howitzers, hundreds of Humvees and 144 Bradley fighting vehicles which will spread out across Eastern Europe.

There hasn’t been a U.S. military deployment in Europe this big since the Cold War.

But as the troops move beyond Zagan, they will fall under the shadow of Russia’s land-based strike missiles in Kaliningrad, the Connecticut-sized enclave squeezed between Poland, Lithuania and the Baltic Sea. Russia has invested heavily in building up its military presence there in recent years.

In the event of a military conflict over the Baltic States, Russian missiles in Kaliningrad could target NATO troops heading from Poland. That could slow reinforcements were Russia to invade Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia.

The Baltics would need those NATO reinforcements to have a chance, slim as it would be, to stop a vastly more numerous Russian army. Indeed, Russia’s army is smaller than it once was, but it is “more than adequate … to overwhelm whatever defense the Baltic armies might be able to present,” a RAND Corporation study noted in 2016.

Kaliningrad’s missiles pose a serious complication to NATO. The enclave is practically loaded with them.

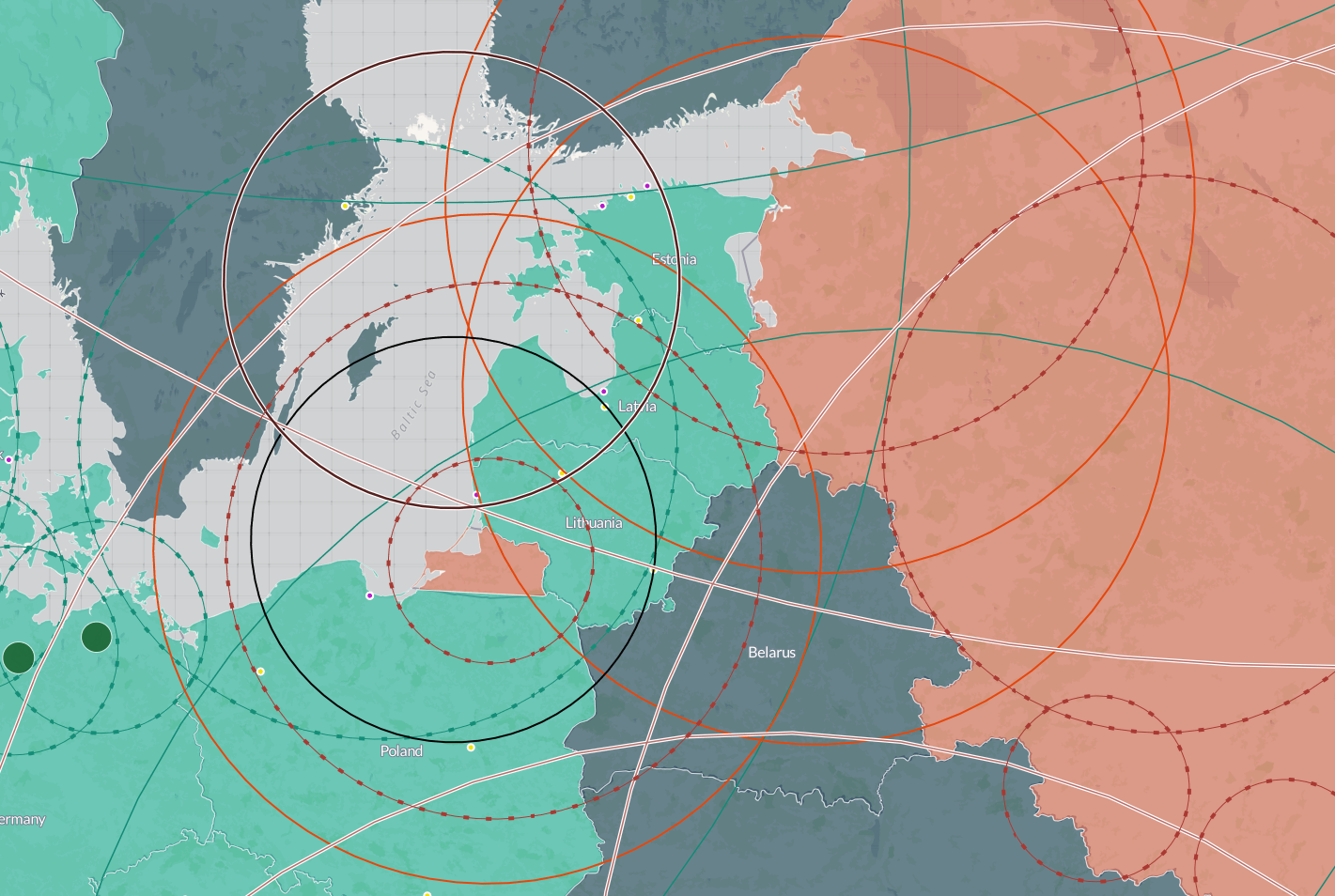

For a visual illustration, here’s an interactive map — larger version here — showing these missile “bubbles” indicating the range of various weapons in Europe. The map was produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington, D.C.-based think thank.

The map can display the ranges of various Russian land attack, air defense and naval strike weapons near its borders. It’s not comprehensive and there are fixed points of reference for naval weapons — which, of course, would vary in location during an actual conflict.

For NATO, you can select options to show the range of the alliance’s land-attack naval weapons and its air defenses, along with the location of key PODS — or ports of debarkations — where the alliance could land reinforcements by air and sea.

While none of this information is new, it is humbling when displayed graphically. Russian Iskander M ballistic missiles, packing 1,500-pound high-explosive warheads, can reach hundreds of miles into Poland. The entirety of the Baltic States, of course, are within range.

On multiple occasions in 2015 and 2016, Russian warships launched SS-N-30 Kalibr cruise missiles from the Caspian Sea into Syria, requiring the missiles to travel from 1,000 miles away. Similar to the U.S. Tomahawk cruise missile, the Kalibrs could likewise reach most of Europe from ships in the Black Sea, the Baltic or from beyond the Arctic Circle.

Russia’s navy has declined since the Soviet era, and is best suited today for coastal defense and regional power projection, but the Kremlin doesn’t need a large navy to fulfill these objectives. In the Caspian, Russia relied on small, Buyan-class missile boats to fire the Kalibrs, which Russia also keeps in its Baltic Sea Fleet.

Air defenses ring Russia’s Western periphery. S-300 and S-400 anti-aircraft missiles cover half of Poland and overlap in concentric circles over the Baltic States — requiring NATO to neutralize these sites during a conflict before its aircraft could provide cover for Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia.

But the map also displays Russia’s clear vulnerabilities.

NATO warships with Tomahawk missiles could easily reach Russia’s biggest cities — and strike the center of government power — from considerable distance away.

No comments:

Post a Comment