BY URI FRIEDMAN

The greatest unknown for U.S. interests in the world might be the United States itself.

Over the last several years, concern about a particular threat to the United States has been steadily rising in a survey of American foreign-policy experts and government officials by the Council on Foreign Relations. On an annual basis, hundreds of respondents estimate the likelihood and impact on U.S. interests of 30 possible conflicts in the coming year. These conflicts are then divided into three tiers of risk to the United States or its closest allies. The poll is an attempt to help U.S. policymakers prioritize dangers in a dangerous world.

In the 2013 and 2014 surveys, respondents wrote in the potential for Russia to interfere in former Soviet states including the Baltic countries, which, like the United States, are members of NATO. In 2015, the scenario appeared for the first time among the survey’s 30 “contingencies,” with an “unintentional or deliberate military confrontation” between Russia and NATO member states regarded as a second-tier risk. This year it was considered a first-tier risk, according to the latest survey, released Monday. A conflict in 2017 between one of the world’s most powerful militaries and the world’s most powerful military alliance was judged moderately likely and high-impact.

One important caveat to the finding is that the survey was conducted from early to mid-November, meaning some respondents submitted their answers before the U.S. election and others did so afterward. “Knowing that [Donald] Trump generally has a positive view of Russia and is seemingly hopeful that U.S.-Russia relations will be better under his presidency, would the respondents have felt that a NATO-Russia contingency deserved such high-level concern?” asked Paul Stares, the director of CFR’s Center for Preventive Action, which produces the survey. “I don’t know.”

When I pointed out that you could just as well draw the opposite conclusion—that Trump’s questioning of NATO’s utility and of America’s commitment to defend fellow NATO members from Russian aggression, along with his apparent fondness for Vladimir Putin and open-minded attitude toward Russian land grabs in Ukraine, could make the scenario more likely—Stares chuckled. That’s also possible, he conceded.

The uncertainty surrounding what a Trump presidency will mean for Russian behavior in Eastern Europe hints at a larger point: The biggest unknown for U.S. interests in the world in 2017 may lie not in Russia or North Korea or the Middle East, but in the United States itself. Trump has consistently suggested that he will depart dramatically, in style and substance, from decades of agreement among Republicans and Democrats on the general outlines of U.S. foreign policy. We simply don’t yet know whether that will enhance or diminish U.S. security and global stability. What can be said with more confidence is that Trump will introduce greater unpredictability into international affairs, perhaps reshuffling the way the world is ordered in the process.

“When you’re looking at how the world might evolve, it’s logically silly to put the U.S. off to the side as if it’s a neutral or passive actor,” Stares told me. “How some of these contingencies evolve reflects very much what the U.S. may do immediately before or during the crisis. [The United States is] just too important a player for it not to have that effect.”

This year’s moderately likely, high-impact risks include not just a showdown between Russia and NATO, but also a major cyberattack on U.S. critical infrastructure—a prominent worry in Washington at the moment following Russia’s suspected meddling in the U.S. election. They also include a “mass-casualty terrorist attack on the U.S. homeland or a treaty ally.” Trump has described terrorism as a much graver threat to the United States than Barack Obama has, and his administration looks set to wage a broader battle against “radical Islam.”

In this category as well is a crisis in North Korea “caused by nuclear or intercontinental ballistic missile weapons testing, a military provocation, or internal political instability.” Obama has reportedly warned Trump that the rapid development of North Korea’s nuclear-weapons program—especially the progress that Kim Jong Un’s regime is making in placing a nuclear warhead on a long-range missile that could reach the United States—should be the top national-security priority for the incoming administration. North Korea has a tendency to take provocative actions during U.S. political transitions, and any deal to halt the North Korean nuclear program would require cooperation from the Chinese government, whose relations with Trump have grown tense over the status of Taiwan.

First-tier risks also encompass highly likely but only moderately impactful events such as the Taliban continuing to gain strength and the government collapsing in Afghanistan; violence escalating between the Turkish military and armed Kurdish groups in Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria; and the Syrian Civil War intensifying as a result of increased foreign involvement in the conflict. Notably, that last scenario has been slightly downgraded from last year, when it was considered both highly likely and high-impact, and thus the top concern for the United States in the survey.

The Syrian war’s “perceived impact on U.S. interests actually fell this year,” Stares noted. “Now I don’t know whether that’s because people feel that the worst is over, or that their earlier fears have not been realized, or that we’re in the endgame” of the conflict.

High-Priority Threats to America

Among the second-tier risks in this year’s survey are violent civil disorder stemming from the political and economic crises in Venezuela, which the respondents considered highly likely but low-impact for the United States, and an armed confrontation between China and its neighbors over disputed territory in the East or South China Seas, which was deemed unlikely but high-impact. Stares said he was surprised that possible clashes between China and U.S. treaty allies like Japan and the Philippines, which could draw the United States into a fight with its most formidable rival, weren’t thought more likely, and that the further breakup of Iraq fell from a first-tier risk in past years to a second-tier risk this year.

Other second-tier risks include turmoil in the European Union caused by the refugee crisis; a military confrontation between India and Pakistan over a terrorist attack or the contested region of Kashmir; a deterioration of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; and greater political fragmentation in Libya. The coming year could also bring more violence from militant groups in Pakistan, Russian-backed militias and Ukrainian security forces in eastern Ukraine, and various foreign and domestic factions in Yemen’s civil war.

The respondents also pointed to two contingencies that didn’t show up in past surveys: political instability in the Philippines from opposition to the new president’s brutal war on drugs, among other policies, and in Turkey from the president’s growing authoritarianism following a failed coup against him. Turkey, for example, could witness widespread protests or another coup attempt. “Sometimes [U.S. officials] look to stable authoritarian governments as being good partners for certain things—they’re predictable and so on—but there is obviously also a downside risk if they are subject to domestic political challenges and unrest,” Stares said.

Medium-Priority Threats to America

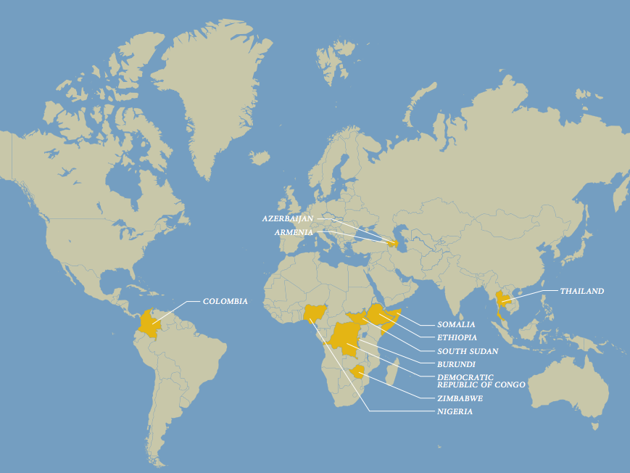

The third tier of risks features scenarios that might have significant humanitarian and geopolitical consequences, but in countries of limited strategic importance to the United States. Among these are political unrest in Burundi, Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Thailand, and Colombia; increased violence from al-Shabab in Somalia and Boko Haram and other militant groups in Nigeria; a deepening of the civil war in South Sudan; a military conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region; and upheaval linked to the succession of Zimbabwe’s longtime dictator, Robert Mugabe.

Low-Priority Threats to America

Respondents also wrote in scenarios that didn’t appear among the 30 listed contingencies, including some that seem plausible as outcomes of Trump’s emerging foreign policy: mounting tensions between China and Taiwan; economic and political volatility in Mexico resulting from U.S. trade and immigration policies; and a confrontation with Iran over the collapse of the Obama administration’s nuclear agreement with Iran and other world powers—a deal Trump has repeatedly criticized.

Assessing the impact Trump’s policies could have on the scenarios in the survey, Stares cited the president-elect’s vow, at a rally celebrating his election victory, to build up the U.S. military not “as an act of aggression” against other countries, but “as an act of prevention.” Trump is right that a strong military helps deter potential adversaries, Stares argued, but it’s a necessary rather than sufficient condition for peace. If he “thinks that somehow military strength is the principal prescription for peace, or what will really make a difference, then I think he’s misguided,” Stares said. “Securing peace relies on a lot more efforts by the U.S. on many different levels if [Americans] really want to avoid conflict.” The United States having the world’s most powerful military “didn’t prevent Iraq from invading Kuwait” in 1990, he noted. “It didn’t deter al-Qaeda from attacking” the U.S. on 9/11.

“Every new administration is tested by a crisis,” Stares added. “And the initial [test] typically doesn’t go well.”

No comments:

Post a Comment