By Erica Chenoweth for Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

17 Nov 2016

Nonviolent resistance has been a surprisingly effective method of political change and its use has spread around the world. In this brief, Erica Chenoweth highlights some of the recent developments in this form of defiance, including a puzzling and sudden decline in the effectiveness of nonviolent resistance since 2010, and the surprising lack of state support for such campaigns.

Nonviolent resistance has been a surprisingly effective method of political change and its use has spread around the world. In this brief, Erica Chenoweth highlights some of the recent developments in this form of defiance, including a puzzling and sudden decline in the effectiveness of nonviolent resistance since 2010, and the surprising lack of state support for such campaigns.

This article was originally published by the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) in 2016.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Nonviolent resistance has been a surprisingly effective method of political change. Moreover, it is becoming an increasingly common practice around the world. This policy brief highlights some key trends in nonviolent resistance–including a puzzling sudden decline in the effectiveness of nonviolent resistance since 2010, an increase in the number of violent flanks within otherwise nonviolent uprisings, and the surprising lack of direct state support for such campaigns. The brief concludes with implications for policymakers concerned with human rights and democracy assistance.

Brief Points

Nonviolent resistance is on the rise, even as violent forms of resistance are on the decline.

Nonviolent mass uprisings can be swift, effective, and extremely difficult to predict.

However, nonviolent resistance has declined in its effectiveness since 2010, even as it has become a more widely adopted technique. Activists need skills, knowledge, protection from repression, and an engaged and prepared civil society to mobilize effectively.

Nontraditional forms of assistance–such as support from international nongovernmental organizations or transnational solidarity networks–may be more influential in supporting activists seeking change through nonviolent resistance than direct state support.

Nonviolent Resistance around the World

Nonviolent or “civil” resistance is a technique of struggle where unarmed civilians use a coordinated variety of methods–like demonstrations, strikes, and other forms of noncooperation–to confront their opponents. Unlike armed insurgencies or guerrilla attacks, nonviolent resistance is a form of struggle that builds and applies power without harming or threatening to harm an opponent. Most people who engage in nonviolent resistance are not pacifists, but rather use nonviolent resistance because it is the most pragmatic option available to them for creating change. That being said, many pacifists have used nonviolent resistance in their own struggles.

Some form of nonviolent resistance has occurred in every country in the world regarding various limited or reformist claims. But nonviolent uprisings with maximalist demands to overthrow incumbent governments or to create new territories through self-determination are also ubiquitous. From Ghana to Guatemala, from Bosnia to Ecuador, from Tunisia to Fiji, and from Zimbabwe to Tonga, maximalist nonviolent campaigns have become increasingly common around the world.

Nonviolent campaigns tend to lead to people-powered democratic transitions, which also tend to be fairly stable (Chenoweth & Stephan 2011; Celestino & Gleditsch 2013).

With several different co-authors, I have been collecting systematic data on this phenomenon for ten years, focusing specifically on popular campaigns aiming to remove incumbent national leaders from power, expel foreign military occupations, or secede (Chenoweth 2016; Chenoweth & Lewis 2013; Chenoweth & Stephan 2011; Stephan & Chenoweth 2008). This data collection has resulted in several important findings relevant to policymakers concerned with human rights and democracy assistance.

Definitions

The primary unit of analysis here is an uprising, which is defined as a series of contentious acts by non-state actors linked or coordinated through common participation and/or leadership for more than one week. I use the words “uprising,” “episode,” and “campaign” synonymously. In this policy brief, I present data related to maximalist uprisings, which demand removal of the incumbent national leader or territorial independence through secession or self-determination. The systemic effects of their claims differentiate these uprisings from reformist campaigns, such as those seeking economic, social, cultural, or political reform. One can reasonably classify an episode as either nonviolent or violent based on the primary method of contention, the presence of arms, and the number of injuries or fatalities.

Violence is defined as an action or practice that directly physically harms or threatens to physically harm another. Those who engage in violent action are typically armed, and their actions involve shootings, bombings, armed assaults, hit-and-run attacks, assassinations, and conventional military engagements. Data on violent uprisings are gathered using the Correlates of War database criteria, which identifies them as all cases in which there have been more than 1000 battle deaths (including at least 100 caused by each side of the conflict) in a sub-state conflict (see Gleditsch 2004).

Nonviolent action is defined as action by an unarmed person or persons that applies force to another without using or threatening physical harm. Data on nonviolent uprisings are gathered by triangulating other published protest data sources and conducting original searches in Lexis Nexis for new episodes.

Notably, an episode is classified as a nonviolent one if the activists are using nonviolent methods; the opponent government typically uses violence–sometimes massive violence–against the participants. In fact, opponent governments used lethal violence against about 90% of the nonviolent episodes in the dataset.

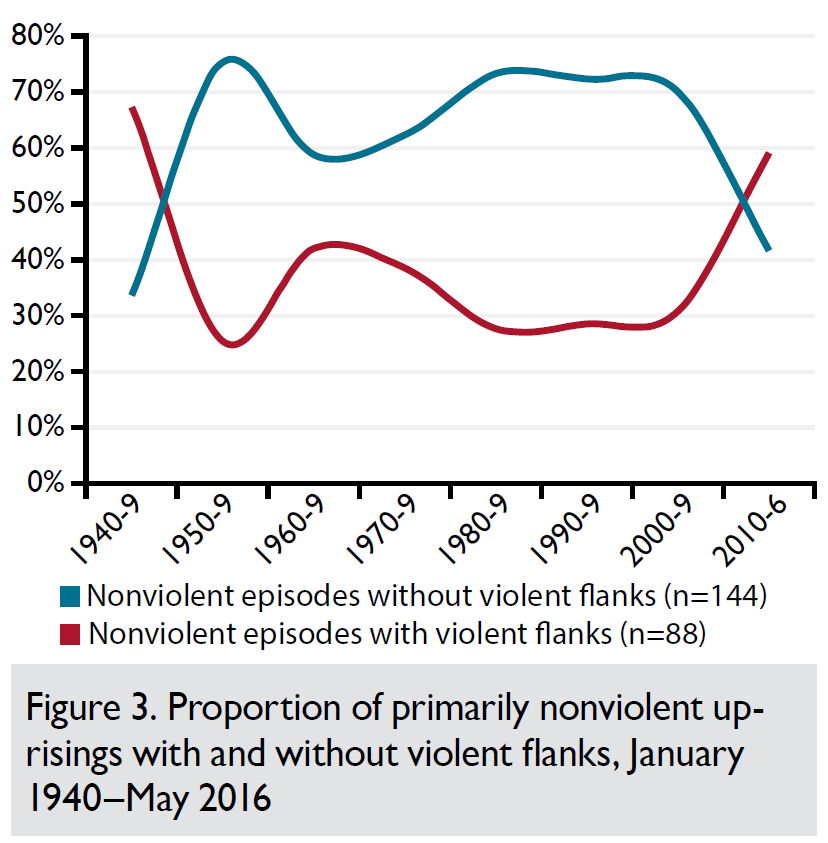

Sometimes uprisings classified as primarily nonviolent do involve a limited amount of protester-led violence. Although 62% of the nonviolent episodes did not perpetrate violence or property damage against opponents over the course of the uprising, 38% of primarily nonviolent uprisings possessed a minimal level of violence (such as rioting, arson, or beatings of police). We call these violent groups in otherwise nonviolent uprisings “intra-movement violent flanks.” Even in those cases with violent flanks, the violence tended to be spontaneous, unplanned, occasional, and incidental to the larger nonviolent uprising.

Success is defined as the achievement of a maximalist outcome (removal of a national leader through irregular means, or territorial independence) within a year of the uprising’s peak mobilization. The uprising had to have had a discernable impact on the outcome.

State support is defined as the provision of material assistance by a sovereign state (funds in the case of nonviolent uprisings, and money, arms, or territorial sanctuary in the case of armed uprisings).

Is Nonviolent Resistance on the Rise?

Figure 1 depicts the decline in onsets of violent civil conflicts, as documented by many recent scholars (Goldstein 2011; Pinker 2011). Less commonly understood is the rise of nonviolent resistance–perhaps an even more dramatic trend than the decline in violent conflict onsets.

Indeed, maximalist nonviolent uprisings have outnumbered violent ones since 1900 and seem to be on the increase in recent decades especially. Figure 1 suggests an increase in the number of new non-violent campaigns since Gandhi’s struggle against British colonialism in India, which began in 1919. But onsets of nonviolent uprisings began to accelerate in the late 1960s, during a wave of anti-colonial struggles that dominated the times. In the late 1980s, the iconic Eastern European revolutions drove a surge in new uprisings, as did a growing number of movements against US-backed right-wing military regimes in Latin America. The number of nonviolent uprisings has steadily increased since then, featuring a sustained period of “color revolutions” against post-communist regimes between 2000 and 2010, followed by an even more geographically diverse set of cases since then. Since 2010 alone, we have seen well over 50 new major nonviolent uprisings around the world, including the Arab Uprisings of 2011, Guatemala, Burkina Faso, and Hong Kong. It is not an exaggeration to say that as nonviolent resistance goes, we live in the most contentious decade witnessed in the past 100 years.

Nonviolent uprisings are exceedingly difficult to predict (Chenoweth & Ulfelder 2015). As a result, observers are often caught off guard by their onsets and are surprised at the swiftness with which these mass movements often sweep away entrenched, decades-old regimes in a matter of months.

Is Nonviolent Resistance Becoming More Effective?

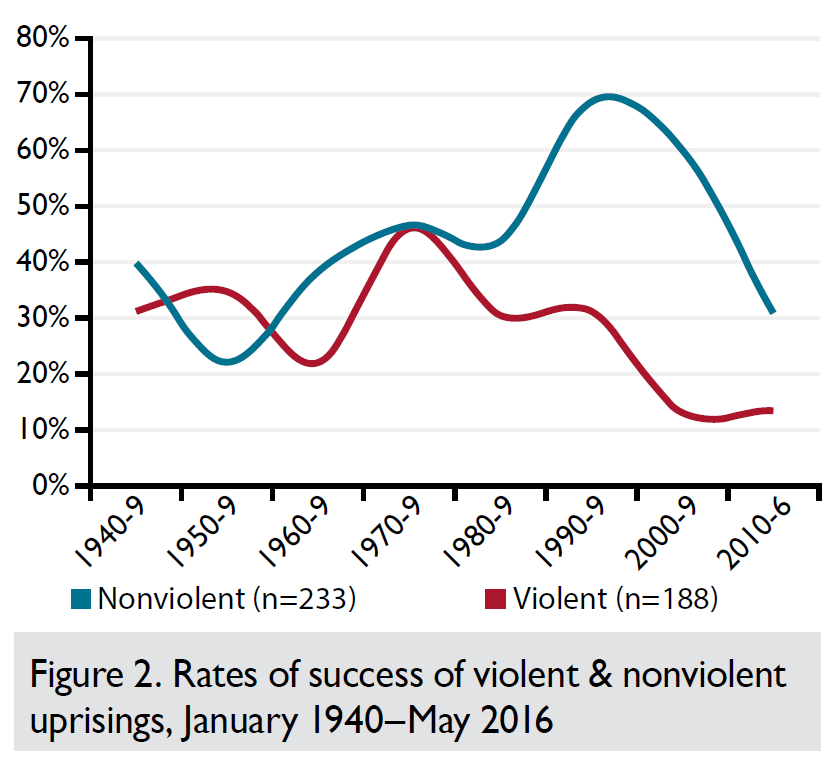

In fact, historically, nonviolent resistance has been surprisingly effective compared to its violent counterparts (Chenoweth & Stephan 2011). From 1900–2015, about 50% of maximalist campaigns of nonviolent struggle succeeded, compared to about 25% of violent insurgencies (Chenoweth 2016) – a rate similar to that reported in the NAVCO data set (Chenoweth & Stephan 2011; Chenoweth & Lewis 2013). In general, the primary driver of success for nonviolent uprisings is that nonviolent uprisings feature a much larger number of active participants, yielding a wide variety of potentially disruptive tactics (Chenoweth & Stephan 2011). For example, general strikes–one of the most effective methods of nonviolent action (Hamann, Johnston, & Kelly 2013) – are effective only when participation is widespread.

Indeed, as Figure 2 illustrates, nonviolent resistance has been an impressively effective method up to 2010, when it began to decline in effectiveness. Several trends may be responsible for the sudden decline in the success rates of maximalist nonviolent uprisings. First, their opponents may be improving in their ability to withstand, contain, or suppress such challenges (Chenoweth 2015). Second, attempts at nonviolent resistance may be less effective as the technique becomes popularized, leading some to adopt methods of resistance that may not be appropriate to their own contexts (Weyland 2009). Third, the ease with which people can organize using digital technology may paradoxically undermine the success of their contentious efforts, since many uprisings may develop before civil society has the capacity to sustain a resilient campaign over a significant duration. More research is needed to better understand the cause. Fourth, it may be that a higher proportion of primarily nonviolent uprisings tolerate, embrace, or fail to contain violent flanks. As Chenoweth and Schock demonstrate, non-violent uprisings with accompanying violent flanks tend to feature lower rates of participation, leading to lower rates of success than their wholly nonviolent counterparts (2015). The higher proportion of violent flanks in uprisings since 2010–the highest proportion since the 1940s–may be leading to higher rates of campaign failure (Figure 3).

Of course, the increase in violent flanks may also be a function of reverse causality: as nonviolent episodes result in fewer successes, more participants may turn to violence out of frustration. More research is required to determine whether violent flanks lead to failure, or whether campaign failures are leading to violent flanks.

How Often Do States Support Nonviolent Activists Abroad?

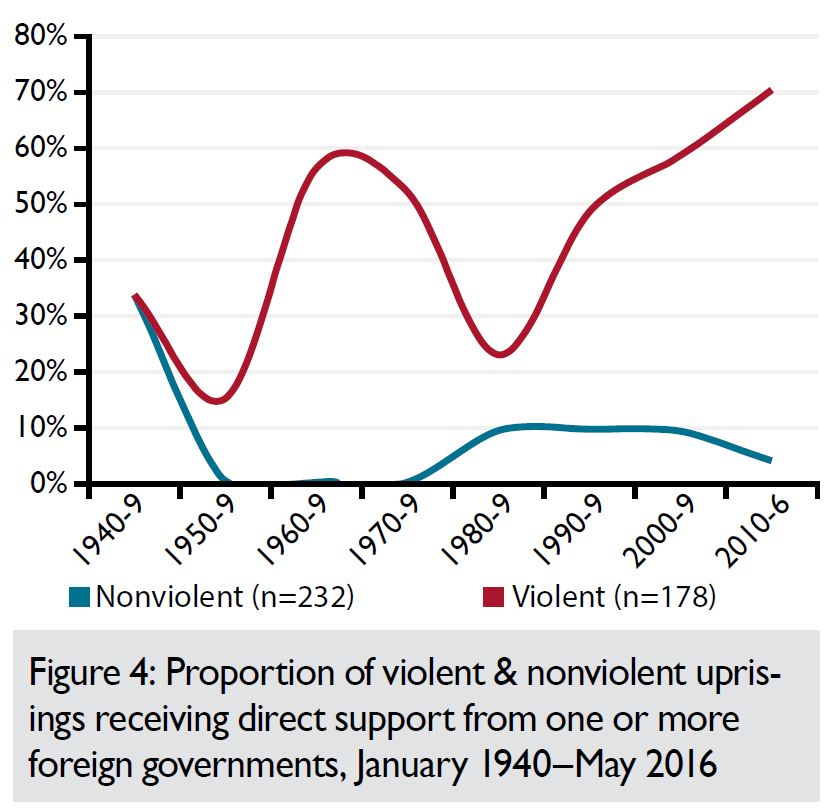

Despite routine accusations that nonviolent uprisings are conspiracies of foreign powers meant to undermine sovereign governments to spread their pro-democracy agendas, only 7.2% of nonviolent uprisings from 1900–2016 received direct support from a foreign state. In contrast, 38.3% of armed groups received direct support from foreign governments. Figure 4 depicts the rates of state support to nonviolent and violent uprisings since 1940.

This fact greatly undermines cynical claims that these unarmed revolutions are the product of conspiratorial efforts by foreign agents to sponsor “color revolutions” to unseat or destabilize leaders of rival powers. Instead, it appears that nonviolent uprisings cannot be imported or exported.

At the same time, this finding also yields a crucial implication–that many nonviolent uprisings have historically succeeded without much support from states. In fact, some have argued that external assistance by states may actually hurt nonviolent campaigns, as it feeds into the opponent’s propaganda that these uprisings are sponsored by outsiders and foreign agents (Chenoweth & Stephan 2011). As democratic governments become concerned about “closing space” for civil society around the world (Carothers and Brechenmacher 2014) – and the declining effectiveness of nonviolent uprisings in the past few years–they should tread carefully regarding the different policy instruments they use to support such campaigns.

Summary of Findings

Nonviolent resistance is on the rise, even as violent forms of resistance are on the decline.

Nonviolent resistance has been a surprisingly effective technique of major political change, outperforming violent resistance by an impressive margin.

Nonviolent resistance has declined in its effectiveness since 2010, even as it has become a more widely adopted technique.

Contrary to critiques of nonviolent uprisings as “soft coups”, nonviolent uprisings are not (and cannot be) imported or exported into other countries.

Implications for Policymakers

Four key policy implications can be derived from these trends.

Nonviolent resistance is a major factor in shaping the world today. Because such uprisings can be swift, effective, and extremely difficult to predict, policymakers should be aware that authoritarian governments are often more fragile than they appear. Rather than assuming that closed states are stable, policymakers should understand that decades-long rule is no longer a reliable indicator of stability.

Activists using nonviolent resistance have struggled to be effective in recent years. This may be due to growing repression against them, a failure to integrate effective methods of nonviolent resistance due to lack of knowledge, a tendency to mobilize before civil society is prepared to sustain a resilient campaign, or a greater prevalence in violent flanks within otherwise nonviolent movements. All of these possible factors suggest that activists need protection from repression, skills, knowledge, and an engaged and prepared civil society to mobilize effectively.

However, traditional forms of assistance by states to these uprisings are rare; nor do they appear necessary for them to succeed. Nontraditional forms of assistance–such as support from international nongovernmental organizations or transnational solidarity networks–may be more influential in supporting activists seeking change through nonviolent resistance than direct state support. The Diplomat’s Handbook on Democracy Development and Support (Kinsman & Bassuener 2012) provides a number of useful suggestions for how diplomats can serve as conveners to put movements in touch with NGOs, INGOs, or other activists who can assist such movements.

Policymakers should dedicate more resources to the study of nonviolent resistance and dissemination of knowledge about nonviolent action.

Acknowledgements and Disclaimer

Sections of this brief are adapted from an article published by the author in The Diplomatic Courier called “Why Is Nonviolent Resistance on the Rise?” on June 28, 2016.

Cited Works & Further Reading

Carothers, Thomas & Saskia Brechenmacher (2014) Closing Space: Democracy and Human Rights Support under Fire. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Celestino, Mauricio Rivera & Kristian Skrede Gleditsch (2013) ‘Fresh carnations or all thorn, no rose? Nonviolent campaigns and transitions in autocracies’, Journal of Peace Research 50(3): 385–400.

Chenoweth, Erica (2016) The major episodes of contention data set, v1. Unpublished data set, University of Denver.

Chenoweth, Erica (2015) ‘Trends in civil resistance and authoritarian responses’, in Maria J. Stephan and Mat Burrows, eds, Is Authoritarianism Staging a Comeback? Washington, DC: Atlantic Council.

Chenoweth, Erica & Orion Lewis (2013) ‘Unpacking nonviolent campaigns: Introducing the NAVCO 2.0 data’, Journal of Peace Research50(3): 415–423.

Chenoweth, Erica & Kurt Schock (2015) ‘Do contemporaneous armed challenges affect the outcomes of mass non-violent campaigns?’, Mobilization: An International Quarterly 2(4): 427–451.

Chenoweth, Erica & Maria J. Stephan (2011) Why civil resistance works: The strategic logic of nonviolent conflict. New York: Columbia University Press.

Chenoweth, Erica & Jay Ulfelder (2015) ‘Can structural factors explain the onset of nonviolent uprisings?’, Journal of Conflict Resolution(forthcoming).

Gleditsch, Kristian Skrede (2004) ‘A revised list of wars between and within independent states, 1816–2002’, International Organizations 30(3): 231–262.

Goldstein, Joshua (2011) Winning the War on War. New York: W. W. Norton.

Hamann, Kerstin, Alison Johnston, & John Kelly (2013) ‘Striking concessions from governments: The success of general strikes in Western Europe, 1980–2009’, Comparative Politics 46(1): 23–41.

Kinsman, Jeremy & Kurt Bassuener (2012) The Diplomat’s Handbook on Democracy Development and Support. Community of Democracies.

Pinker, Steven (2011) The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined in the 21st Century. New York: Viking.

Schock, Kurt (2005) Unarmed Insurrections: People Power

About the Author

Erica Chenoweth is Professor and Associate Dean for Research at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver. She was an Associate Senior Researcher at PRIO from 2012–2015. With Maria Stephan, she won the 2013 Grawemeyer Award for Ideas Improving World Order for their book Why Civil Resistance Works.

No comments:

Post a Comment