By Elaine Ou

NOV 21, 2016

India is conducting a big test of the idea that getting rid of cash can help address crime and corruption. Unfortunately, it might achieve nothing more than a lot of inconvenience.

Criminals and corrupt officials often conduct business in cash, because it's hard to trace. So in a sense it’s logical to assume that abolishing cash will help reduce criminal activity. Scandinavian countries such as Norway and Sweden, after all, have extremely low cash usage rates and also lead the world in the lack of perceived corruption.

Criminals and corrupt officials often conduct business in cash, because it's hard to trace. So in a sense it’s logical to assume that abolishing cash will help reduce criminal activity. Scandinavian countries such as Norway and Sweden, after all, have extremely low cash usage rates and also lead the world in the lack of perceived corruption.

This rationale has led Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to declare a surprise cancellation of the nation’s two highest-denomination notes, effectively invalidating 86 percent of total currency in circulation. Anyone with outstanding notes must either deposit them in a bank -- potentially incurring a tax -- or exchange them for replacements in strictly limited sums.

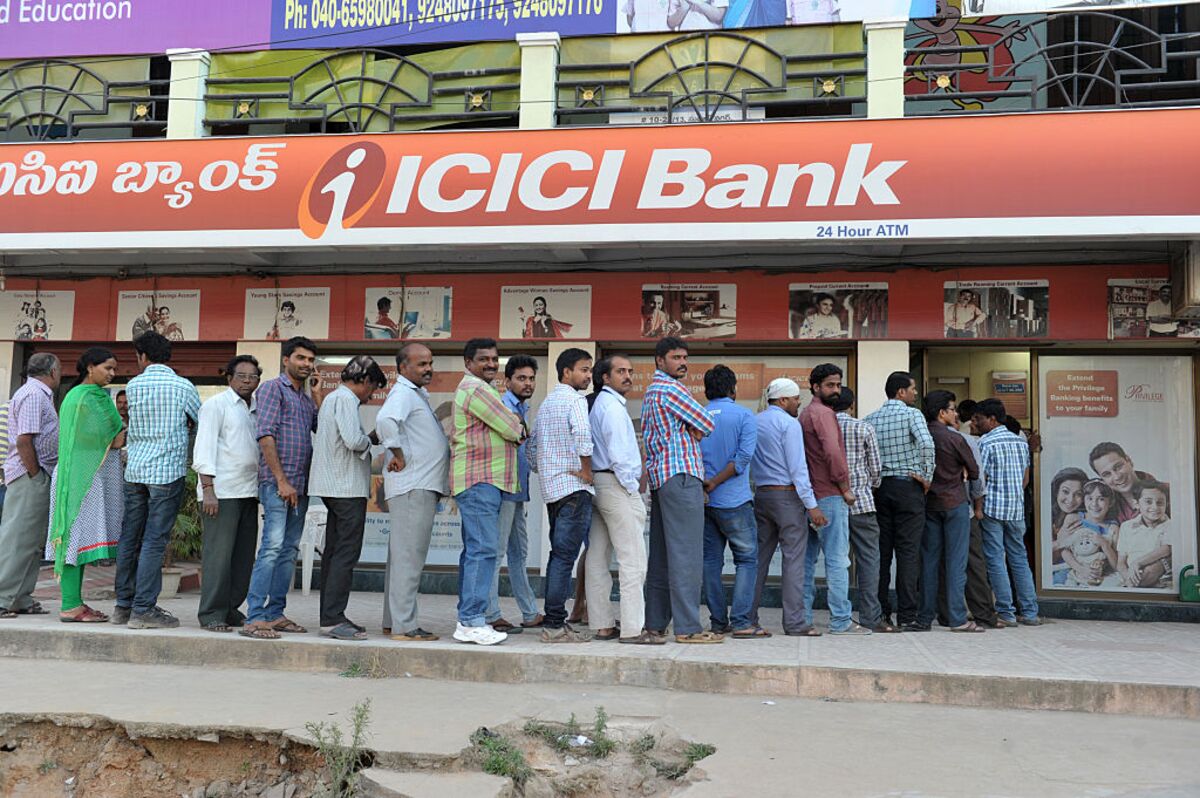

The move has already proven immensely disruptive, though not entirely to criminals. In a country where most transactions are conducted in cash, many people have been unable to pay fornecessities like food or medical services. Banks have had to work overtime to handle the exchange, bringing other financial services to a halt.

It's certainly likely that the sheer trauma will leave people less keen to hoard rupees, creating a big incentive to move economic activity out of cash and into banks. Except that a huge number of Indians don’t have a bank account.

In any case, the prevalence of cash is far from a foolproof indicator of criminality and corruption. Consider Nigeria, which is perceived as one the world's most corrupt countries and has a currency-to-GDP ratio even lower than Sweden’s:

Who Has Cash

Source: Kenneth S. Rogoff, "The Curse of Cash."

Nigerians have abandoned cash because they have so little trust in government-issued currency. Instead of using banks, they tend to transact in mobile airtime minutes. Some rural villages even create their own credit instruments, enforced by local deities. Those with more substantial wealth put it in foreign currency.

By undermining faith in its cash notes, India may go the way of Nigeria. Villagers are already resorting to barter. A peer-to-peer cash-to-bitcoin app called LocalBitcoins has seen volume spike. As of Monday, Bitcoin was trading on Indian exchanges at a 25-percent premium to the global average. Even before the note-swap announcement, many tax-evaders and corrupt public officials were believed to have their wealth in real estate and gold.

Those who want to fight corruption by policing cash may have the causality backwards. Scandinavian countries have discouraged illicit activity by creating a culture of financial transparency. Norway and Sweden, for example, make all tax returns publicly available. It’s harder to enjoy your illegal gains when your neighbors can easily check your lifestyle against your finances. The countries’ ability to weather financial crises also instills trust in the banking system.

Granted, this doesn't strike me as an easy solution for India, which sits much closer to Nigeria than to Norway in global corruptionrankings. Unless the government can guarantee people's safety, publishing information on citizens' wealth -- even just for public officials -- could serve primarily to provide robbers and extortionists with a convenient shopping list.

In India's case, using monetary reform to herd people into the financial system might accomplish the exact opposite. Cash alternatives could prove even harder to control than the national currency. Somehow, trust and transparency have to come first.(Corrects reference to tax on deposits in third paragraph and number of Indians without bank accounts in fifth paragraph.)

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Elaine Ou at elaine@globalfinancialaccess.com

No comments:

Post a Comment