by PIERRE SAUTREUIL

This fall, the Chinese embassy in Bishkek transformed into a medieval stronghold. Beneath its bulky walls, police officers carrying Kalashnikovs patrol ceaselessly. Bustling on the edge of muddy trenches, workers erected a new row of bulwarks.

This fall, the Chinese embassy in Bishkek transformed into a medieval stronghold. Beneath its bulky walls, police officers carrying Kalashnikovs patrol ceaselessly. Bustling on the edge of muddy trenches, workers erected a new row of bulwarks.

Inside the compound, a wide crater and smashed windows revealed the brutality of an Aug. 30 attack that struck the Chinese representation in Kyrgyzstan. A suicide bomber crashed a van filled with explosives through the embassy’s main gate, before detonating it in the middle of the courtyard.

Only three employees were hurt, but the shock wave reached Beijing in a heartbeat. It was the first time in recent history China was so violently targeted in Central Asia.

During the course of the last 10 years, China has overshot Russia as the main economic partner for the five former Soviet “Stans” — Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. This trend has gained speed since economic sanctions and falling oil prices grounded Moscow’s investment capacity.

In January, the Kyrgyz parliament voted to cancel two major hydropower construction deals with Russian companies, citing “serious shortcomings” and incapacity to show any progress. China inherited the deal in April.

Chinese banks have financed the renovation of several roads and power lines in Kyrgyzstan. In Tajikistan, 60 percent of all direct foreign investments came from China in 2015 — eight times more than Russia.

In Turkmenistan, a country sitting on a tenth of the world’s natural gas reserves, Chinese banks lended billions of dollars to stimulate gas production. And in Kazakhstan, China now controls around 30 percent of the country’s oil production, according to Ardak Kasymbek, managing director of the state energy company KazMunayGas.

Beijing’s strategic interest in Central Asia mostly lies in the region’s formidable reserves of energy and raw materials, but there is more to it than that.

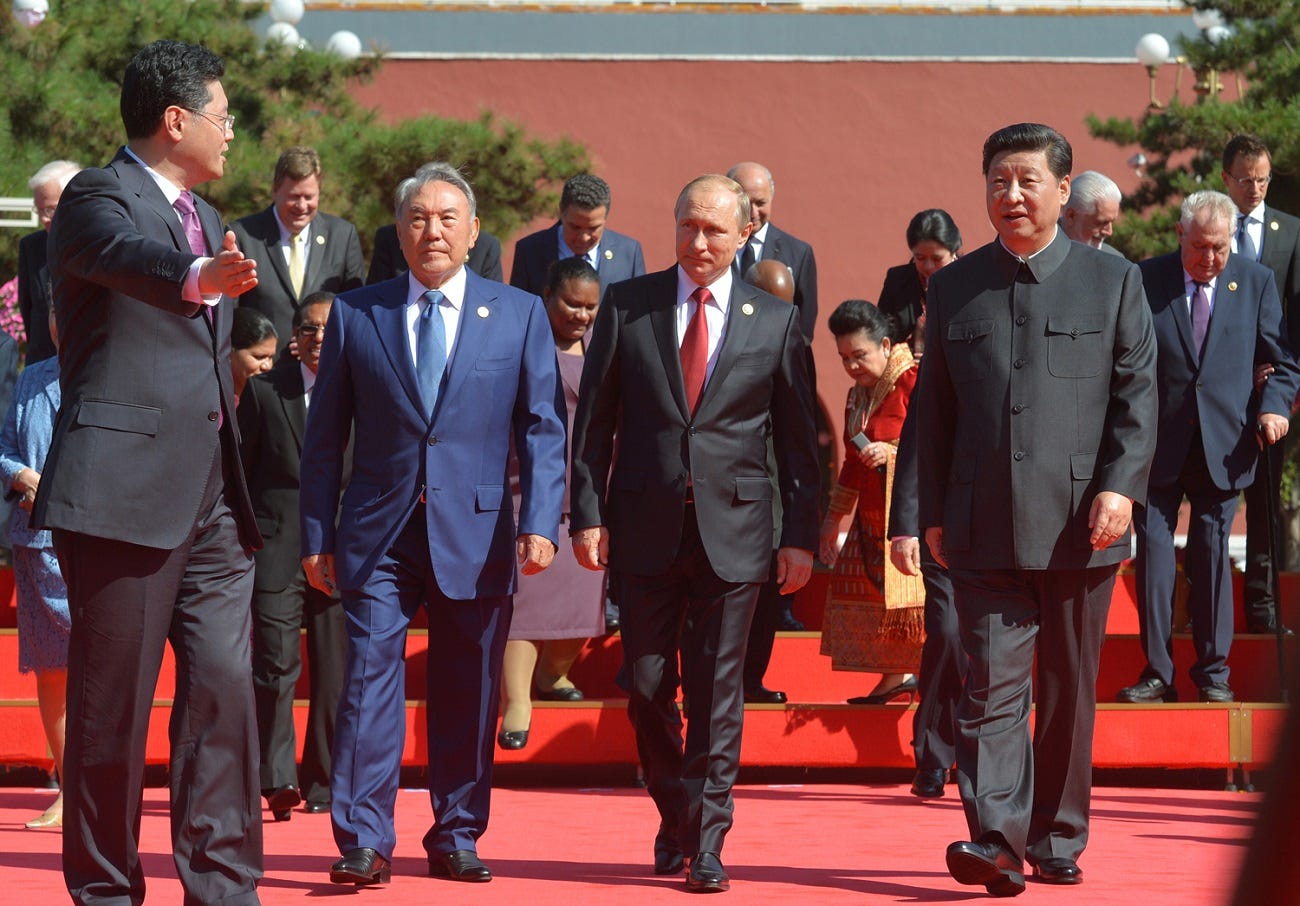

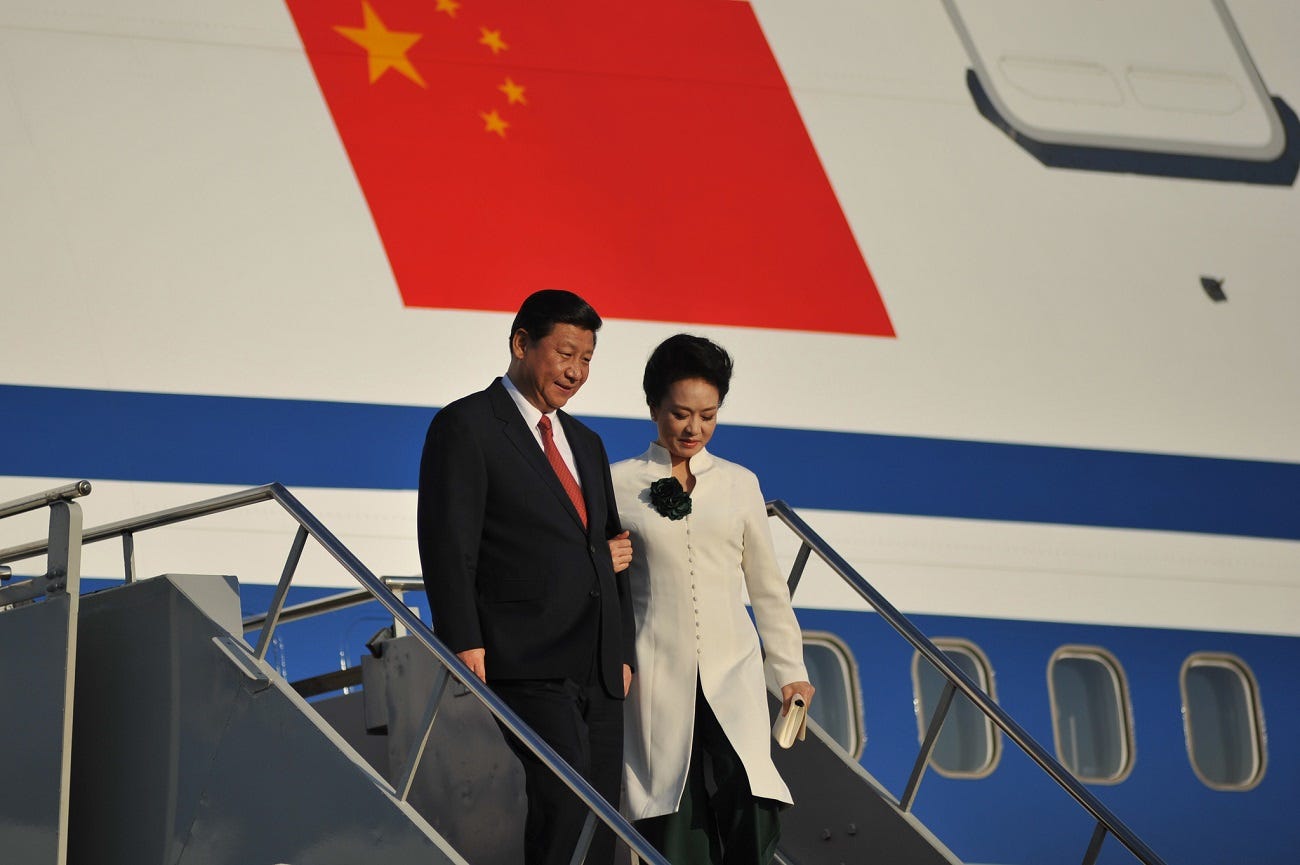

It was in Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan, that Chinese president Xi Jinping presented the “One Belt One Road” project, so far his most significant foreign policy concept, in September 2013.

The aim of this initiative, also known as “The New Silk Road,” is to revive the ancient roads that connected China to Europe and the Middle East throughout the centuries, in order to boost trade — and incidentally stabilize Central Asia, a region undermined by institutional instability, drug trafficking and Islamic terrorism.

According to the Kazakh Institute for Strategic Studies, China has invested around 10 billion dollars in Kazakhstan since Xi’s speech, and the number of Chinese firms working in the country has increased by 30 percent.

“The Chinese have poured tremendous sums on the region, it’s only natural they want guaranties for their investments,” Kazakh Sinologist Ruslan Izimov said.

Among Beijing’s biggest preoccupations for the region are its vicinity to Afghanistan, the recent upsurge of jihadist attacks, and the presence of Uighur minorities — a Muslim people undergoing a severe crackdown in Western China.

Beijing has suspected Uighur militants to be behind the Bishkek embassy attack.

“When Libya and Yemen foundered into war, China lost billions of dollars and had to evacuate its citizens in an urgent fashion,” Izimov said. “The trauma is still fresh, which is why the Bishkek attack was such a shock for Chinese diplomats.”

During his official visit in Kyrgyzstan on Nov. 2 as part of a summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, Chinese prime minister Li Keqiang said the security situation in Central Asia was “complicated and severe.”

Such a grave tone uncloaked China’s determination to increase its role in the region’s security matters, previously an area reserved to Russia. China has stepped up security throughout 2016 with an unprecedented effort, in order, as the motto goes, clear the region of the “three evils:” extremism, terrorism and separatism.

In August, China presided over the creation of an anti-terror coalition which includes Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan. On Sept. 26, a decree from the Tajik government announced that China would build 11 outposts on its border with Afghanistan, a lucrative zone for the heroin trade and where skirmishes frequently occur with the Taliban.

On Oct. 24, several hundred Chinese soldiers joined their Tajik counterparts in their first-ever bilateral military drill in Tajikistan, where Russia holds its biggest military base abroad.

More unsettling, according to credible reports published on Nov. 3, it appears Chinese armored personnel carriers recently patrolled the Wakhan Corridor, a narrow strip of Afghan territory squeezed between China, Tajikistan and Pakistan, despite the absence of any agreement allowing this bold move.

“The fact that China is challenging Russia’s security leadership in the region is obviously upsetting for Moscow,” one European diplomat said.

Signs of irritation have already begun flaking Russia’s opaque diplomatic varnish. During the SCO summit in Bishkek in November, Li Keqiang offered to transform the organization into a free-trade zone.

Russian prime minister Dmitri Medvedev politely brushed off the proposition, as it would gut the febrile Eurasian Economic Union, a Russian-led customs union extending to Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

Such words hint at a growing disharmony between the two giants, but silence can be even more eloquent. “The Russians have not officially reacted to China’s renewed involvement in the security of the region, which speaks volumes about how tensed they are about it,” the diplomat added.

Such words hint at a growing disharmony between the two giants, but silence can be even more eloquent. “The Russians have not officially reacted to China’s renewed involvement in the security of the region, which speaks volumes about how tensed they are about it,” the diplomat added.

Does that mean one should fear an escalating rivalry between Russia and China? “It’s not the Cold War anymore,” says Luca Anceschi, lecturer in Central Asia studies at the University of Glasgow.

“What we see at the moment is a rather efficient Russian-Chinese condominium over the region, and the situation in Kazakhstan and in Kyrgyzstan tells both influences can coexist, since the SCO and the EAEU both remain very vague structures.”

Indeed, Russia and China tend to respect a tacit “division of labor,” with Russia maintaining its hold on most of the security and military issues of the region — while boasting “anti-terror successes” in Syria to terrorism-stricken Central Asian governments — and providing their Soviet-modeled armies with armament, equipment, training and military doctrine.

China, however, has recently muscled its way into the regional arms market, providing Uzbekistan with medium-to-long-range HQ-9 surface-to-air missiles.

In April 2016, Turkmenistan’s state T.V. showcased the military firing HQ-9s. Even more significantly, Beijing has sold several Pterodactyl drones — developed by Chengdu Aircraft Industry Group — to Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, highlighting Russia’s inability to produce such drones.

Overall, China’s global weapons exports have almost doubled over the past five years, boosted by fast-paced technological progress and affordable prices.

Of additional concern is America’s declining influence in the region, symbolized by the closure of the Manas airbase near Bishkek in 2014, and the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan.

This disengagement is expected to continue under Donald Trump’s presidency, leaving Russia and China face to face in Central Asia.

However, Central Asian governments might pose even more difficulties to China’s security efforts than the Kremlin. Despite the annexation of Crimea, regional elites remain attached to Russia, and anti-Chinese sentiment is widespread among local populations.

In 2015, nationalist groups raided Chinese-owned clubs and restaurants in Bishkek, a series of actions that appeared to be supported by the Kyrgyz secret services.

In April 2016, a law allowing Chinese investors to rent farming lands for long periods of time sparked the biggest protests in Kazakhstan since violent riots in 2011.

Appeasing these fears is now a crucial issue for China.

“The Chinese leadership understands that too much investment can produce rejection, as locals feel invaded and dispossessed, it is a major limit to their foreign policy,” Kazakh expert Daniyar Kosnazarov said. “They try to increase their soft power, but it will be a very long endeavor.”

It appears that education is among China’s favorite medium for influence. In Kazakhstan, several Confucius Institutes — which promote Chinese language and culture— have opened their gates, and university exchange programs are developing every year.

In 2014, only 7,800 Kazakh studied in China. This figure now exceeds 12,000.

No comments:

Post a Comment