BY URI FRIEDMAN

OCTOBER 20, 2016

Controlling territory is at the core of the group's ideology, but it isn't everything.

Territory is arguably both ISIS’s greatest strength and its greatest weakness. The land the group seized in Syria and Iraq, which at its peak was thought to be as large as the kingdom of Jordan, enabled the Islamic State to aspire to its grandiose name by declaring a caliphate, drawing recruits from around the globe, and distinguishing itself from the world’s stateless terrorist and insurgent groups.

Territory is arguably both ISIS’s greatest strength and its greatest weakness. The land the group seized in Syria and Iraq, which at its peak was thought to be as large as the kingdom of Jordan, enabled the Islamic State to aspire to its grandiose name by declaring a caliphate, drawing recruits from around the globe, and distinguishing itself from the world’s stateless terrorist and insurgent groups.

But that land has also served as a big, fat target for ISIS’s enemies, who have been pummeling the organization from the air and on the ground. By one estimate, ISIS has lost 16 percent of its territory so far in 2016, after losing 14 percent in 2015. It has recently retreated from the Iraqi cities of Ramadi and Fallujah, the Syrian-Turkish border, and the Syrian town of Dabiq, where ISISmembers once prophesied a literally apocalyptic battle with infidel armies. This week, a motley crew of forces launched a massive assault on ISIS’s last Iraqi stronghold of Mosul.

Each square mile lost chips away at ISIS’s reason for being. As my colleague Graeme Wood wrote last year, “Caliphates cannot exist as underground movements, because territorial authority is a requirement.” What exactly is the Islamic State, if the “state” all but disappears?

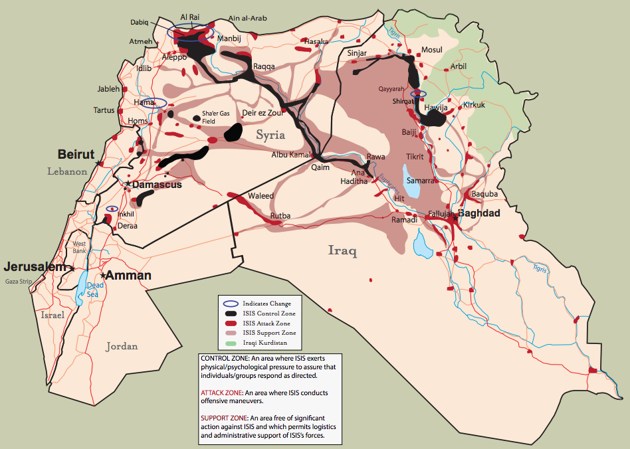

Black indicates territory ISIS controls, dark red indicates territory where ISISconducts attacks, and light red indicates territory where ISIS enjoys some degree of support. (Institute for the Study of War)

To answer that question, I turned to William McCants, a scholar of Islamic militancy at the Brookings Institution and the author of TheISIS Apocalypse: The History, Strategy, and Doomsday Vision of the Islamic State. We spoke about how territory factored intoISIS’s early ideology, how its leaders have explained their recent setbacks, how the group reconciles its dual goals of building a caliphate and bringing about the end of the world, and how the organization could change in the coming years.

McCants argued that a stateless Islamic State could still carry out terrorist attacks abroad and exploit political dysfunction in Syria and Iraq, even as it struggles to attract foreign fighters and justify its claim to the caliphate. Most of all, I was struck by the timeline he offered for defeating the idea of ISIS as opposed to its physical footprint. The group, he emphasized, accomplished what other jihadist organizations had long dreamt of by controlling substantial territory. “ISIS’s own leaders have said it will take a generation of being denied territory for the effect of that to fade,” he told me. “I think that’s right.”

An edited and condensed transcript of our conversation follows.

Uri Friedman: ISIS came to a lot of people’s attention in June 2014 when it seized Mosul and declared a caliphate. So many people have only known ISIS as a terrorist group that controls significant territory. But ISIS had been around [in various forms] for a decade before it took control of Mosul. How did the organization’s early leaders, including [founder] Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, think about territory and the notion of a physical caliphate?

William McCants: They wanted it. It was Zarqawi who cooked up the scheme to reestablish the caliphate in the area between Mosul and [the Syrian city of] Aleppo. He dreamed it up when he was hiding out in Iran in 2002 after fleeing Afghanistan following theU.S. invasion. He saw the coming U.S. invasion of Iraq as an opportunity to get that land. His plan was to sow a civil war

No comments:

Post a Comment