October 12, 2016

Amid the snake-infested marshlands on Iran’s border with Iraq, the control room monitoring North Azadegan oil field is manned entirely by Chinese technicians. In central Tehran, hundreds of Chinese pour out at noon from the telecommunications company Huawei to its canteen. There are now so many Chinese expatriates here, some say they outnumber all other nationalities combined.

Amid the snake-infested marshlands on Iran’s border with Iraq, the control room monitoring North Azadegan oil field is manned entirely by Chinese technicians. In central Tehran, hundreds of Chinese pour out at noon from the telecommunications company Huawei to its canteen. There are now so many Chinese expatriates here, some say they outnumber all other nationalities combined.

A decade of international sanctions aimed at blocking Iran’s nuclear program has left China the country’s dominant investor and trade partner. Now, with those restrictions formally lifted, a more pragmatic Iranian government has been trying to ease dependence on China, only to find itself stymied by hard-line resistance and residual U.S. sanctions.

“China has done enough investment in Iran,” said Mansour Moazami, who was deputy oil minister until taking over as chairman of the massive Industrial Development & Renovation Organization this year. “We will provide opportunities and chances for others.”

The tension illustrates a more nuanced situation in post-sanctions Iran than is often presented. Many in the U.S., including Donald Trump, portray Iran as the big winner from last year’s nuclear sanctions deal as European companies rush into one of the world’s last big, untapped emerging markets. Yet in Tehran, the government is attacked for failing to deliver and pandering to a still hostile West.

Western investors have been slow to arrive, forcing Iran back into the arms of the Chinese. That’s especially true in the energy sector, where pressure to increase production is intense. Elsewhere, Western clearing banks still refuse to do business with Iran for fear of falling foul of non-nuclear U.S. sanctions that remain in effect, meaning Western companies can’t raise project finance.

People including Moazami are becoming frustrated. His state conglomerate wants to raise $10 billion of foreign investment by the end of next year, for projects from shipbuilding to petrochemicals. “We need investment. What we expected has not happened yet, and this is what we need the Americans to solve,” Moazami said. It is unclear whether new U.S. guidelines on sanctions published Oct. 7 will change the situation.

A “sense of being cheated” by the West is slowly sinking in among Iranians, according to Li Guofu of the Chinese Foreign Ministry’s Institute of International Studies. “China sort of knows Iran is aware they actually don’t have a great deal of options.”

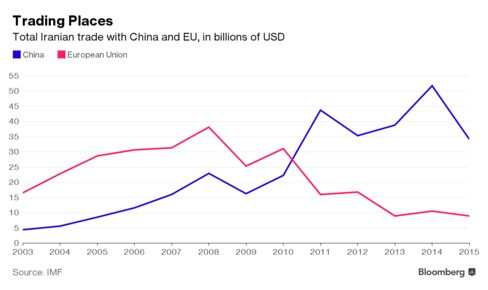

The sanctions period was a boon for China because other countries forced their companies to leave. From trading half as much with Iran as the European Union before sanctions, China had five times as much Iran commerce as the EU by 2014, tailing off since due to the falling price of oil.

From oil to automobiles to communications, Chinese companies moved in, often gaining their first major international contracts, said Majidreza Hariri, vice president of the Iran-China Chamber of Commerce. Mobile operator Huawei Technologies Co., for example, is building communications infrastructure in Iran, work that would otherwise have gone to Germany’s Siemens AG, he said.

Rebuild Ancient Routes

China now wants to take the relationship further, hoping to rebuild its ancient Silk Road trade routes to Europe. In January, President Xi Jinping was the first world leader to visit Tehran after sanctions ended, promising $600 billion of trade over 10 years.

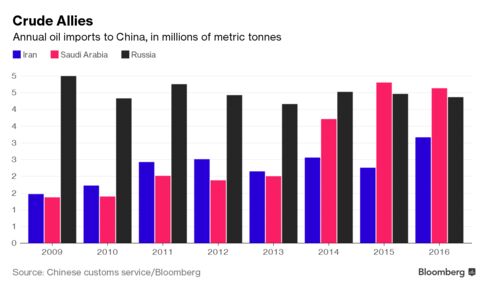

Yet the relationship has rarely been smooth. Although China has been one of Iran’s most important sources of weaponry and nuclear technologies since the 1980s, its leaders sacrificed those projects at key moments to protect relations with the U.S., according to a detailed account by John Garver of the Georgia Institute of Technology. When it needed more oil, China turned first to Saudi Arabia, Iran’s bitter rival.

Iran, too, has proved ambivalent, as its relationship with the world’s rising superpower became entangled in battles between moderates and conservatives. China won many of its contracts under former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, at a time when he was expanding the role of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps throughout the economy. Now the government of President Hassan Rouhani wants to rebuild investment ties with other parts of the world and reduce the military’s economic footprint.

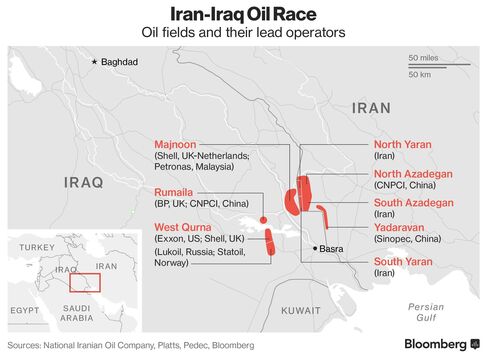

Nowhere has this complex Chinese-Iranian relationship played out more clearly than in the marshes and deserts of the North and South Azadegan oil fields, in southwestern Iran.

A signpost directs traffic between oil fields, on a road cut through the marshes.

Photographer: Marc Champion/Bloomberg

China National Petroleum Corporation International took over in 2010, after sanctions forced Japan’s Inpex Corp. to leave, a pattern repeated at several other big Iranian oil and gas projects. Things began well, but then the Chinese slowed down, especially at the larger southern field, said Karamat Behbahani, the Texas-educated director of the North Azadegan project. The Chinese blamed pressure from the U.S. among other factors, he said.

Close all those tabs. Open this email.

After Rouhani replaced Ahmadinejad in 2013, the government began to complain loudly of Chinese failures to deliver. An Iranian company replaced the Chinese at a $4.7 billion offshore contract. In 2014, Oil Minister Bijan Zanganeh kicked the Chinese out of the South Azadegan oil field, one of the world’s largest greenfield projects with about 33 billion barrels in place. Other Chinese investments could be at risk, too, he warned.

China’s role hit a further low in 2014, when an environment official fined Chinese workers for hunting and eating soft-shelled Euphrates turtles, a protected species, in the sensitive wetlands that surround North Azadegan’s oil wells. (On a recent visit, water buffalo waded in the shallows and a mongoose climbed out of the reeds to rip the head from a snake.)

Pressure to develop Azadegan was growing, however. Iraq had contracted a consortium led by Royal Dutch Shell Plc to tap the reservoir it shares with Iran from the other side of the border. In April 2014, the Iraqi side exported its first shipment of oil.

Two Straws

“It’s as though you have a nice cold drink with two straws in it,” said Behbahani, noting that Iraq was sucking on the other straw. “We should not lose any time.”

Behbahani said that while Western companies may have better technology than CNPCI, the Chinese were in place. Shell’s team is now pumping more than 200,000 barrels per day, compared to a combined 125,000 barrels at the two Azadegan fields.

“We did what we had to do, based on our national interest,” said Behbahani in his Tehran office. “If Total had been here, it would be Total taking the oil out. If it had been Shell, Shell.”

At South Azadegan, without a foreign investor, the engineers in charge said they’re still four years away from completing the surface equipment needed to produce at full capacity. It’s lack of cash that’s slowing progress, rather than technology, they said -- even if they are envious of some Shell software that quickly maps out underground reservoirs, saving time and money.

Zanganeh, the oil minister, said in May that he was in talks with Total SA to take over South Azadegan, which is expected to be put up for tender later this month. But contract delays and the electoral calendar mean it’s likely to be at least 18 months before any big Western oil company starts work on an Iranian oil field, according to Homayoun Falakshahi, of Wood Mackenzie energy consultants. Total did not return phone calls and e-mail requests for comment.

In the meantime, Iran has softened its stance on Chinese investment, announcing exclusive talks with Chinese firms to continue with the second phases of the North Azadegan and nearby Yadaravan oil fields.

Zanganeh also seems to have compromised with conservative factions at home. The new international oil contract passed by parliament requires foreign investors to choose from a short list of licensed partners, including a conglomerate belonging to the Revolutionary Guard and another associated with Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

New Contracts

“This says to the regime’s conservatives that they won’t be excluded from the new contracts,” said Falakhshahi. Last week, the first of the new-style contracts -- to exploit the Yaran fields, smaller neighbors to North and South Azadegan -- went to an affiliate of the Supreme Leader’s conglomerate, Persia Oil and Gas Industry Development Co.

Iran’s oil ministry did not respond to requests for comment. The head of CNPCI in Iran declined to be interviewed for this article, as did the Chinese embassy in Tehran. CNPC’s headquarters in Beijing did not respond to e-mail and telephone requests for comment.

Since the nuclear deal was reached, CNPCI has upped the pace at North Azadegan, hitting its 75,000 barrel-per-day contract commitment four months ago. That may be several years late, but “we aren’t holding our heads in our hands,” said Behbahani. With the help of a Chinese, rather than Western, oil company, Iran has begun sucking on its straw.

(An earlier version of this story was corrected to show that the North and South Azadegan oil fields are in southwestern Iran.)

No comments:

Post a Comment