Stratfor, 20 July 2016

Summary

As China tries to overcome slowdowns in its industrial and trade sectors, the country’s banks have continued to increase the pace of lending, issuing 1.38 trillion yuan ($205.8 billion) worth of loans in June. The figure confirms some economists’ expectations that lending will keep rising as China’s central government attempts to revive economic growth and boost property markets that showed signs of another slump in May. It also indicates that despite Beijing’s repeated pledges to reduce the economy’s reliance on credit and state-led investment, the easy flow of financing from state-owned banks remains the country’s primary bulwark against widespread debt crises among corporations and local governments.

As China tries to overcome slowdowns in its industrial and trade sectors, the country’s banks have continued to increase the pace of lending, issuing 1.38 trillion yuan ($205.8 billion) worth of loans in June. The figure confirms some economists’ expectations that lending will keep rising as China’s central government attempts to revive economic growth and boost property markets that showed signs of another slump in May. It also indicates that despite Beijing’s repeated pledges to reduce the economy’s reliance on credit and state-led investment, the easy flow of financing from state-owned banks remains the country’s primary bulwark against widespread debt crises among corporations and local governments.

Analysis

The June credit figure, according to official data released July 15, followed a sharp hike in formal bank lending between April and May, suggesting that recent government efforts to increase the state-owned banking sector’s share of nationwide financing are on course. It is difficult to overstate the scale and intensity of the transformation undergone by China’s financial system since the 2008 global financial crisis, which compelled the Chinese government to embark on what now looks likely to become a decade long (or longer) stimulus drive. In 2007, state banks issued 3.6 trillion yuan worth of new loans. Their lending has since increased each year, reaching 11 trillion yuan in 2015.

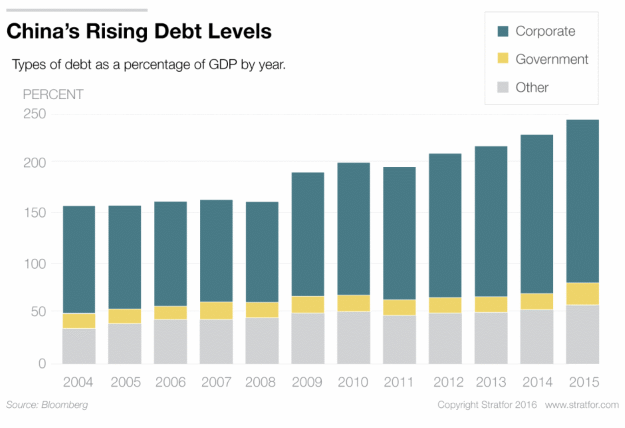

Meanwhile, total social financing — encompassing state-controlled and informal loans — ballooned to 15.9 trillion yuan last year. Outstanding local government debts remain at manageable levels, but corporate debt, much of which does not enjoy the state’s backing against default, equals more than 175% of China’s national economic output. Officially, only 1.75% of total outstanding loans are considered nonperforming, or likely to be defaulted on. Most independent analysts, however, expect the genuine nonperforming loan rate to be much higher.

Shifting a New Paradigm

The explanation for this surge in credit and investment is remarkably straightforward. But the solutions to the many problems it has generated for China’s long-term economic health are not. The credit boom began as a response to the collapse in demand for Chinese goods in 2007. It was aimed primarily at shoring up employment by expanding infrastructure construction, and secondarily at industrializing China’s largely rural interior.

But what was intended as a temporary emergency response soon morphed into a new paradigm for the Chinese economy, thanks in part to prolonged weakness in demand for goods and to a political structure that encouraged unchecked growth. For nearly a decade, credit and investment have buttressed Chinese economic (and, in turn, social and political) stability, emerging as the mainstays of the country’s gross domestic product — equal to 44% in 2014 — and as the principal drivers of employment, especially in China’s less developed inland regions. During that time, questions of credit — who can extend it, who can take it on as debt, how it is spent, and how it is repaid — have come to determine the architecture of China’s political economy.

For each of these questions, the past year or so has brought noteworthy developments. For example, after seeing their share of aggregate financing dip between 2011 and 2013, yuan-denominated loans, virtually all of which originate in state-owned banks, have steadily regained their former primacy in the Chinese financial system. At the same time, many forms of nongovernmental or informal financing that rose in prominence during waves of tighter government credit controls have gradually declined in importance. The result is that as China’s economic slowdown deepens, an ever-greater share of outstanding debts, including a growing mountain of bad debts, will fall under the purview of the country’s major state-controlled banks.

Piling those debts onto the state’s balance sheet entails risks, especially if defaults rise. But for Beijing, the risks of a financial crisis among informal and shadow lenders beyond the state’s control would be far greater. A crisis that China’s leaders can measure and trace is better, in Beijing’s view, than one in which the government is batting blind.

The share of loans issued by state-backed banks in China has risen, as has the amount of money they have loaned out. Beijing’s strategy makes sense as the economy sputters, but it raises some long-term questions. (WANG ZHAO/AFP/Getty Images.)

The share of loans issued by state-backed banks in China has risen, as has the amount of money they have loaned out. Beijing’s strategy makes sense as the economy sputters, but it raises some long-term questions. (WANG ZHAO/AFP/Getty Images.)

Tools to Manage a Crisis

Another important change in recent years involves the creation of municipal bond markets and the expansion of a debt swap program that allows localities to trade costly, fast-maturing outstanding loans for cheaper, slower-maturing bonds. The program reduces the risk of local government debt defaults in the near term by pushing back the maturity date for outstanding debts and lowering borrowing costs. In addition, it marks a first step toward giving local governments greater autonomy (and responsibility) over financing and making the process by which local governments raise capital more transparent and easier to measure. Local governments in China pay for upward of 90% of all infrastructure construction while taking home a much smaller fraction of tax revenue.

In the past, local governments covered the cost through a combination of land sales and loans taken out on their behalf by poorly regulated private entities called local government financing vehicles. In 2015, after the rise of bond markets, local governments issued bonds worth 3.5 trillion yuan, nearly all of which took the form of debt swaps that cut local government interest payments by some 200 billion yuan, according to a government report released in March. The government plans to expand municipal bond issuance to as much as 6 trillion yuan by 2017 and 15 trillion yuan before 2020.

Neither those changes nor other ones underway in China’s financial system amount to the broad and ambitious reforms long promised by the country’s leadership. These are tools for managing a crisis, not reconfiguring an economy. As such, they are sure to disappoint observers in and outside China who hoped that President Xi Jinping would move boldly to reduce the economy’s dependence on the state. But given the scale of debt accumulated during the struggle to maintain macroeconomic stability in the past eight years, and considering the complex knot of political interests that exacerbated the excesses of that period, the financial tools and the policy approach they represent are reasonable and unsurprising.

After all, their goal is not to produce a “rational” economy per se, but to preserve the state, even if doing so means accruing innumerable and perhaps insurmountable economic “irrationalities” in the meantime.

“China Is Building Its Future on Credit” is republished with permission of Stratfor.

No comments:

Post a Comment