If ever the famous aphorism, dating back a century or more, about generals always fighting the last war rings true, it is in the war against cybercrime.

The essence of the venerable line is we may well learn from the last battle but we don’t appreciate the same lessons won’t apply in the next one. The lessons of trench warfare didn’t apply when conflict shifted to the air.

With cybercrime, it is the essence of the threat that it constantly changes. The threat is always evolving, changing shape, and defences designed to defeat last week’s breach may not work next week.

It is with this reality firmly in mind that the Basel-based global regulator, the Bank for International Settlements, has had a committee looking at cyber resilience for financial market infrastructures.

The project, under the auspices of the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and the Board of the International Organisation of Securities Commissions, has just released submissions by major market players in response to itsposition paper of November 2015.

The project aims at not just building resilience against crime but against other systemic issues, such as technology failures or seemingly random events like ‘flash crashes’.

ULTIMATE DEFENCE

The sobering reality is there is no ultimate defence against intrusion. Those in the industry have a version of another famous aphorism, the poker one, which says if you don’t know who the patsy in the game is, it’s you.

In financial services the line runs if you think you haven’t suffered a breach that just means it’s happened and you don’t know.

Hence the BIS is perfectly correct in focussing on resilience, not prevention.

The work focusses on financial market infrastructures (FMIs), noting “FMIs can be sources of financial shocks, such as liquidity dislocations and credit losses, or a major channel through which these shocks are transmitted across domestic and international financial markets.”

“In this context, the level of operational resilience of FMIs, including cyber resilience, can be a decisive factor in the overall resilience of the financial system and the broader economy.”

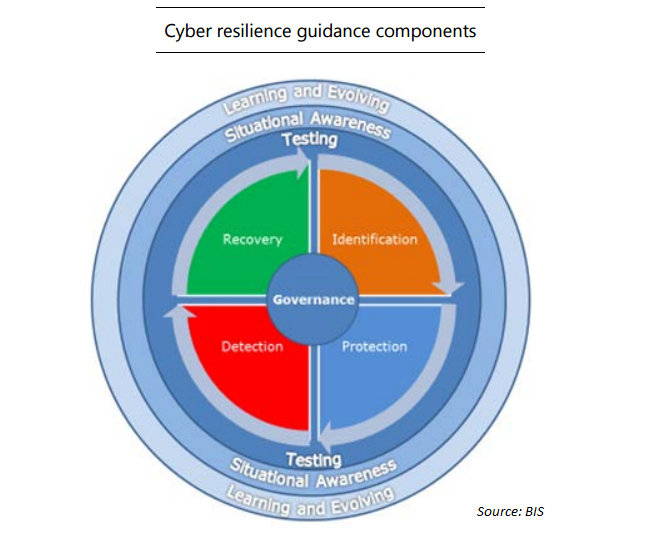

To understand and respond to cyber threats, the BIS committees have broken down resilience into categories and practices.

“The risk management categories are: governance; identification; protection; detection; and response and recovery,” theconsultative report says. “The overarching components are: testing; situational awareness; and learning and evolving.”

The two dozen responses to the document released over the weekend, from government bodies, regulators, market operators and infrastructure providers, reveal general agreement with the principles. But they also highlight the challenges markets face.

For example, ASX, the Australian market operator, notes it has four FMIs in its corporate group.

“We believe that the most practical approach for an organisation with multiple FMIs is for the group’s parent entity or Board (or Board Committee) to have ultimate responsibility for cyber resilience matters,” the ASX said.

“Clearly documented governance arrangements could set out the arrangements for responsibility of cyber resilience matters for the entire group. ASX further believes that duplication of individual cyber resilience strategies and/or frameworks for each FMI under a group arrangement would be inefficient and thus supports a combined approach.”

Now that makes sense - in theory. The challenge will be for sufficient, efficient communication for each operating market to both be subordinate to its head board but have the flexibility to move rapidly when a threat is detected.

ASX also pointed out the FMIs are not closed eco-systems. This has been particularly evident in recent breaches, for example one involving the central bank of Bangladesh, the global SWIFT financial messaging system and the banking system of the Philippines.

NOT CLEAR

While the final details are not yet clear, it seems likely the breach was an internal one in Bangladesh, which meant SWIFT didn’t recognise the fraudulent transfer of money (because it came from an authorised account) but once the money ended up in the Philippines tracking it back was almost impossible.

As the ASX noted in general “there are limitations to the extent that an FMI can control or influence the cyber risks borne by other participants in that ecosystem and therefore believes that an FMI’s responsibility should amount to management of their own risks, while communicating with other stakeholders in the ecosystem, as appropriate”.

The German Bundesbank made a similar point: “It should be noted that there are limitations to getting information related to cyber resilience from the ecosystem especially e.g. from ancillary industry such as Microsoft.”

Several respondents, including ASX, argued arbitrary time frames to resume operations didn’t properly recognise reality. Resuming in two hours, as suggested, seems fraught.

SWIFT said there are “scenarios for which this recovery time objective is unrealistic, particularly in complex cyber scenarios where the detection of the problem can, on average, take 200 days, according to industry statistics. In some instances it may even be an undesirable objective, as reopening service too quickly could promulgate a cyber issue though the financial system”.

The specifics of responsibility are also a challenge. The global payments platform Visa noted it “sees the benefit in clearly defining the remit of the responsibilities in organisations for those who are involved in the key processes in a cyber-resilience framework.”

“However, [Visa] believes that accountability for cyber resilience is a shared organisational issue, requiring each area of the business to be accountable and responsible for various aspects of cyber resilience,” it said.

“For instance, compliance with cyber resilience may be enforceable by the area of the organisation principally managing risk, whereas the legalities of cyber resilience policies may be checked by the legal department.”

CLEAR LESSON

These are all valid points. Meanwhile cyber threats continue to mount and thousands of breaches, from the minor to potentially major, occur in markets daily.

The clear lesson is market operators, regulators and ancillary providers need to behave more like the criminals: constantly evolving, constantly testing and probing, constantly revisiting protocols.

‘Agile’ methodologies, the current fad in project management, do actually encapsulate how organisations need to be organised: rapidly responding, learning from each iteration, being prepared for unpredictability.

While the practice of war is constantly changing, the motivations behind wars have barely changed through human history. So too the motivations of cyber criminals in financial markets. The American bank robber Willie Sutton (perhaps apocryphally) summed it up when asked why he robbed banks: “Because that’s where the money is”.

Today he would be armed not with guns but a keyboard and stolen data.

Andrew Cornell is managing editor at BlueNotes

No comments:

Post a Comment