Stratfor, 6 June 2016

Summary: Japan was the first nation to enter a period of secular stagnation, deflationary tendencies, and fertility collapse. Now Europe and America are following (in our own ways). Decades of extreme monetary and fiscal stimulus have stabilized the economy, but at the cost of falling incomes for many of its people. Since we are on the same path, watch Japan to see the challenges we’ll face in the future. Abenomics’ failure gives Japan’s leaders nothing but harsh choices, but they appear paralyzed.

Summary: Japan was the first nation to enter a period of secular stagnation, deflationary tendencies, and fertility collapse. Now Europe and America are following (in our own ways). Decades of extreme monetary and fiscal stimulus have stabilized the economy, but at the cost of falling incomes for many of its people. Since we are on the same path, watch Japan to see the challenges we’ll face in the future. Abenomics’ failure gives Japan’s leaders nothing but harsh choices, but they appear paralyzed.

Political and economic constraints at home and abroad have brought Japan’s government to a standstill, unable to enact the policies it needs. This paralysis reflects, in part, the limited options available to solve the country’s endemic economic problems. But it also is driven by the interests of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s administration to bolster his ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in July elections for the upper house of the Diet. Those factors have prompted a series of delays and avoidance of policy decisions that underscore the difficulties in tackling Japan’s economic woes in a charged political environment.

Analysis

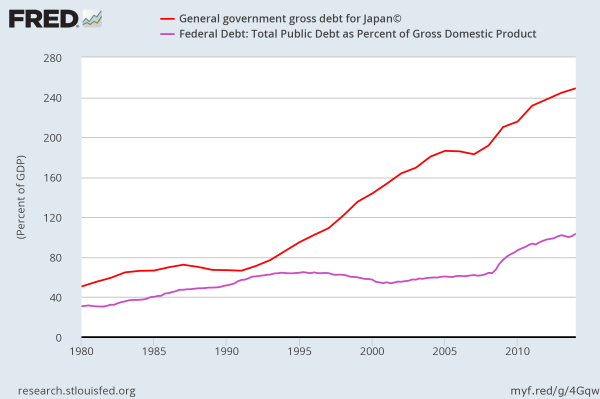

Political and economic considerations played a part in the decision, announced May 31, to delay plans to increase the consumption tax from 8% to 10%. Authorities had planned to implement this tax increase in April 2017 but will now do so in October 2019. In the past, Abe stressed the need for Japan to push ahead with the hike — barring major financial crisis or natural disaster — to address the country’s high national debt (around 245% of gross domestic product). But growing political opposition to the tax increase, not to mention economic indicators showing that the hike could push Japan’s sluggish economy into recession, left Abe with few options.

Comparing government debt/gdp ratios of Japan and US (Federal)

The policy paralysis also stems from domestic economic weakness driven in part by lackluster global economic growth and the slowdown of the Chinese economy. It forms a part of Japan’s decades long saga of seeking to break cycles of persistently weak economic growth and to increase consumption, wages, inflation and productivity levels by overcoming structural deficiencies in its economy.

Economic data for April released May 31 showed weak industrial production and a drop in household spending, in part affected by a series of earthquakes in April. The economic damage from the tremors was not as extensive as expected, but the data refocused the debate on short-term measures to stimulate economic growth and informed the decision to delay the tax hike. Though expedient in the short term, the delay will complicate plans to tackle debt and rein in the budget deficit, forecast to reach 9.56 trillion yen ($89.7 billion) by the end of 2016, not to mention the goal of achieving a budget surplus by 2020.

Growth of GDP (nominal, not after inflation)

“Abenomics,” the prime minister’s strategy to stimulate economic growth through a mix of monetary and fiscal policies as well as structural reforms, has seemingly run its course. The experiment has failed to produce results at least in part because of economic headwinds from abroad. Japan, which barely avoided a recession in the first quarter of 2016, has seen anemic economic growth continue as weak global growth has dragged down Japan’s export revenue and limited foreign direct investment, all as Tokyo struggles to rein in the ballooning public debt. Meanwhile, the structural reform pillar of Abenomics, if successful, will take time to bear fruit — bad news for Japan in the short term.

The Abe administration’s experiments with negative interest rates have thus far been a failure. The administration is now looking to shift its policy focus on fiscal stimulus and is reportedly considering spending as much as 9.6 trillion yen to stimulate growth, a move that will further strain the fiscal system. Japan’s central bank did not introduce negative interest rates in April despite widespread speculation that it would do so.

The previous cut in rates in January failed to produce the desired levels of credit demand, business investment and private spending. Deeper cuts would have presumably helped increase credit growth, but the timing in April was seen as too risky. Not only would deeper rate cuts threaten to undermine support for the administration ahead of the polls, but if the cuts again failed to stimulate business activity, they would have reinforced the already bleak perception of the effectiveness of the administration’s monetary policy. In fact, in its recently released platform for the July 10 elections, the LDP does not make any reference to monetary policy, further suggesting that the policy has run its course.

Meanwhile, debate over the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) has been put off. The LDP and Komeito parties agreed April 25 to sideline deliberations on the trade pact until after the election. This will not have much of an effect on the overall status of the deal, however, since the United States, which is going through its own election cycle, is unlikely to ratify the TPP soon. Without this incentive, Tokyo can focus on electioneering as well as stimulating economic growth. Rather than forcing the TTP issue now, if Abe’s party performs well in upcoming elections, it could use its stronger position to give added weight to future discussions on the trade pact.

The decisions to delay or avoid policies go beyond the short-term imperatives of maneuvering ahead of the polls. They reflect the predicament for an administration that is forced to attempt to enact controversial policies or experiment with new ones to find a way out of Japan’s economic morass — only to realize that no easy solutions exist. Japan’s failure to effectively tackle its economic challenges has undermined its efforts to assume a more robust regional security role, an impetus driven by Tokyo’s desire to counter Chinese economic and military activities and the United States’ yielding of a greater share of the regional security burden to its allies.

As Japan looks beyond elections, the challenge remains: How can the administration give itself more room to maneuver on domestic policy decisions while operating under challenging global economic conditions? The answer, at least in the near and medium term, is clear: There is little it can do to reverse Japan’s economic course. This state of policy paralysis, temporary and expedient as it may be, mirrors Japan’s long-term economic struggles. Unfortunately, there is no easy way out.

“A State of Paralysis in Japan” is republished with permission of Stratfor.

Founded in 1996, Stratfor provides strategic analysis and forecasting to individuals and organizations around the world. By placing global events in a geopolitical framework, we help customers anticipate opportunities and better understand international developments. They believe that transformative world events are not random and are, indeed, predictable. See their About Page for more information.

To understand Japan’s underlying problem, I recommend reading The Enigma of Japanese Power: People and Politics in a Stateless Nation by Karl van Wolferen. Published just before its economy collapsed in 1989, he describes a Japan governed by businessmen and bureaucrats, supported by a public that fears hostile powers threatening their economy, culture, and purity of their race. Japan’s diffuse power structure prevent effective action today, as it did during WWII.

by Karl van Wolferen. Published just before its economy collapsed in 1989, he describes a Japan governed by businessmen and bureaucrats, supported by a public that fears hostile powers threatening their economy, culture, and purity of their race. Japan’s diffuse power structure prevent effective action today, as it did during WWII.

by Karl van Wolferen. Published just before its economy collapsed in 1989, he describes a Japan governed by businessmen and bureaucrats, supported by a public that fears hostile powers threatening their economy, culture, and purity of their race. Japan’s diffuse power structure prevent effective action today, as it did during WWII.

by Karl van Wolferen. Published just before its economy collapsed in 1989, he describes a Japan governed by businessmen and bureaucrats, supported by a public that fears hostile powers threatening their economy, culture, and purity of their race. Japan’s diffuse power structure prevent effective action today, as it did during WWII.

If you liked this post, like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter. See all posts about Japan, and especially these…

As Japan sails into the shadows, let’s wish them well and wave good-by, 2009 — Long stagnation, no signs of a cure.

Japan can again become the land of the rising sun. We should watch and learn from them., 2012 — Falling population & faster automation are great for Japan.

Must our population always grow to ensure prosperity?, 2013 — More about the benefits of a shrinking population & automation.

No comments:

Post a Comment