MAY 22, 2016

A paramilitary police officer stands guard in front of the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region, China on November 17, 2015. © 2015 Damir Sagolj /Reuters

We have followed the law in striking out and relentlessly pounding at illegal organizations and key figures, and resolutely followed the law in striking at the illegal organizations and key figures who follow the 14th Dalai Lama clique in carrying out separatist, infiltration, and sabotage activities, knocking out the hidden dangers and soil for undermining Tibet’s stability, and effectively safeguarding the state’s utmost interests [and] society’s overall interests.

This report documents the Chinese government’s detention, prosecution, and conviction of Tibetans for largely peaceful activities from 2013 to 2015. Our research shows diminishing tolerance by authorities for forms of expression and assembly protected under international law. This has been marked by an increase in state control over daily life, increasing criminalization of nonviolent forms of protest, and at times disproportionate responses to local protests. These measures, part of a policy known as weiwen or “stability maintenance,” have led authorities to expand the range of activities and issues targeted for repression in Tibetan areas, particularly in the countryside.

The analysis presented here is based on our assessment of 479 cases for which we were able to obtain credible information. All cases are of Tibetans detained or tried from 2013 to 2015 for political expression or criticism of government policy—“political offenses.”[1]

Our cases paint a detailed picture not available elsewhere. Stringent limitations on access to Tibet and on information flows out of Tibet mean we cannot conclude definitively that our cases are representative of the unknown overall number of political detentions of Tibetans during this period. But they are indicative of the profound impact stability maintenance” policies have had in those areas, and of shifts in the types of protest and protester Chinese authorities are targeting there.

Information on the cases comes from the Chinese government, exile organizations, and foreign media. Of the 479 detainees, 153 were reported to have been sent for trial, convicted, and sentenced to imprisonment. The average sentence they received was 5.7 years in prison. As explained in the methodology section below, the actual number of Tibetans detained and prosecuted during this period for political offenses was likely significantly higher.

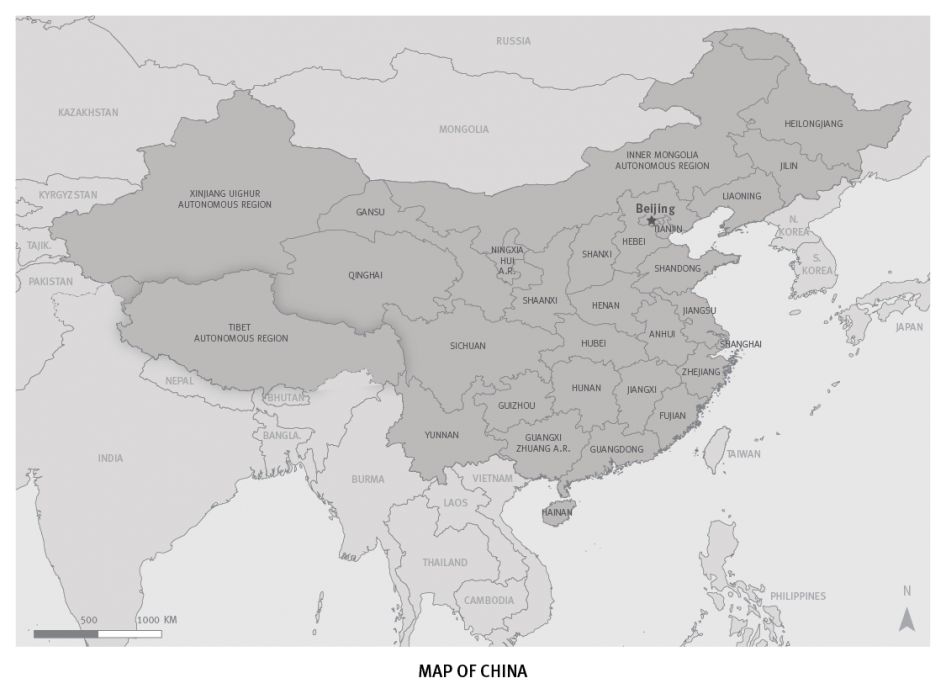

Many detentions documented here were for activities that the Chinese authorities previously considered to be minor offenses or not politically sensitive. Many of those detained came from segments of society not previously associated with dissent. In addition, many of the detentions took place in rural areas where political activity had not previously been reported. From 2008 to 2012, the Tibetan parts of Sichuan province had posted the highest numbers of protests and detentions on the Tibetan plateau, but in 2013 the epicenter of detentions shifted to the central and western areas of the Tibetan plateau, called the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) since 1965, which until 1950 had been under the government of the Dalai Lama.

Our research found that many of those detained and prosecuted were local community leaders, environmental activists, and villagers involved in social and cultural activities, as well as local writers and singers. In the previous three decades, the authorities had rarely accused people from these sectors of Tibetan society of involvement in political unrest. Buddhist monks and nuns, who constituted over 90 percent of political detainees in Tibet in the 1980s, represent less than 40 percent of the 479 cases documented here.

Almost all the protests and detentions identified in this report occurred in small towns or rural townships and villages rather than in cities, where most protests and detentions in prior years were reported to have taken place. This suggests that dissent has increased in rural Tibetan areas, where nearly 80 percent of Tibetans live.

Our data also shows an overall decline in the total number of Tibetans detained for political offenses between 2013 and 2015, though this may be an artifact of the limitations on information, detailed in the methodology section below. Notably, however, the totals for these three years are significantly higher than for the 10 years before 2008 when stability maintenance policies were expanded following major protests centered in Lhasa (Ch.: Lasa), the capital of the TAR.

The changing nature of unrest and politicized detention in Tibet correlates with new phases in the stability maintenance campaign in the TAR and other Tibetan areas. Since 2011, authorities have intensified social control and surveillance at the grassroots level, particularly in the rural areas of the TAR. This has included the transfer of some 21,000 officials to villages and monasteries in the TAR, where they are tasked with implementing new management, security, and propaganda operations, and, more recently, the deployment of nearly 10,000 police in Tibetan villages in Qinghai. This has led to a surge in the creation of local Communist Party organizations, government offices, police posts, security patrols, and political organizations in Tibetan villages and towns, particularly in the TAR.

The implementation of these measures appears to explain many of the new patterns of detention, prosecution, and sentencing documented in this report. It was only after the rural phase of the stability maintenance policy in the TAR was implemented from late 2011 that the number of protests and resulting detentions and convictions increased dramatically in that region.

These detentions, occurring primarily in rural areas, indicate that the stability maintenance policy in the TAR has entered a third phase. The first phase entailed paramilitary operations in the immediate wake of the 2008 protests in Lhasa, when the authorities detained several thousand people suspected of involvement in those protests or associated rioting. The second phase, which began in late 2011 and is ongoing, involved the transfer of officials to run security and propaganda operations in villages, as described above. The third phase, which dates to early 2013, has involved increasing use of the surveillance and security mechanisms established during the second phase in rural villages of the TAR to single out activities deemed to be precursors of unrest. This has meant that formerly anodyne activities have become the focus of state attention and punishment, including social activities by villagers that had not previously been put under sustained scrutiny by the security forces.

In the eastern Tibetan areas—comprising parts of Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu, and Yunnan provinces—politicized detentions also appear to correlate with stability maintenance measures. But in these areas, the government’s measures have been aimed primarily at stopping self-immolations by Tibetans protesting Chinese rule, most of which have taken place in the eastern areas. Beginning in December 2012 the authorities there conducted an intensified drive to end self-immolations among Tibetans that resulted in a sharp increase in detentions and prosecutions of Tibetans for alleged connections to self-immolations, often with tenuous legal basis.

The government’s introduction of grassroots stability maintenance mechanisms in the TAR and of measures against self-immolation in the eastern areas, including in many previously quiet rural areas, has resulted in certain Tibetan localities becoming sites of repeated protests and detentions, producing what could be called protest “cluster sites,” previously unseen in Tibetan areas. These localities saw greater numbers of politicized detentions, recurrent cycles of protest and detention, higher average sentencing rates compared to other areas, and longer sentences for relatively minor offenses.

During 2013-2015, lay and religious leaders of rural communities often received unusually heavy sentences for expressions of dissent, especially if they were from a protest cluster site. Having a sensitive image or text on one’s cellphone or computer could also lead to a long prison sentence, especially though not only if it had been sent to other people. Among those who received the longest sentences were people who tried to assist victims of self-immolations, leaders of protests against mining or government construction projects, and organizers of village opposition to unpopular decisions by local officials. Such activities, most of which were not explicitly political and did not directly challenge the legitimacy of the state, received markedly longer sentences than people shouting slogans or distributing leaflets in support of Tibetan independence.

The incidents described in this report indicate that outbursts of unrest and waves of politicized detentions occurred in specific localities at certain times rather than being evenly dispersed across the Tibetan areas. But the range of locations and the different social levels of protesters involved suggest that political, environmental, and cultural discontent is widespread among Tibetans in many parts of the plateau.

Deaths and ill-health of detainees also continued to be a serious problem in the period covered by this study. Fourteen of those detained, 2.9 percent of the total, were reported to have died in custody or shortly after release, allegedly as a result of mistreatment.

The cases also involve the detention of children, including a 14 and a 15-year-old, both monks, and at least one 11-year-old child detained after his father self-immolated.

The detentions, prosecutions, and convictions documented here reflect the impact of intensive new efforts by officials in Tibetan areas to prevent any repeat of the Tibet-wide protests that occurred in the spring of 2008. Yet the new policies have led to apparently unprecedented cycles of discontent in certain rural areas, and an overall increase in the types of activities that are treated as criminal challenges to the authority of the Communist Party or the Chinese state. The failure of the central government and local authorities to end these abusive policies and roll back intrusive security and surveillance measures raises the prospect of an intensified cycle of repression and resistance in a region already enduring extraordinary restrictions on basic human rights.

No comments:

Post a Comment