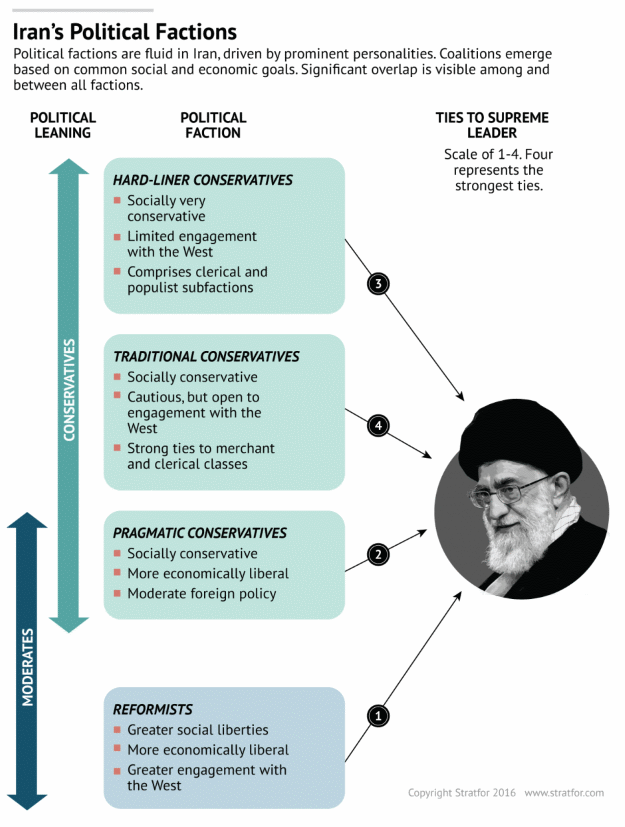

Summary: We tend to see the complex politics of America but assume Iran’s mullahs rule a tyranny. Last week’s elections prove otherwise. Here Stratfor describes Iran’s politics and the election’s results. The new leadership team will have to sail through these troubled waters. Iran’s fragile economy is under incredible pressure from the collapse of oil prices — while the military struggle continues for dominance in the region and the agreement with Obama gives Iran new opportunities.

Summary: We tend to see the complex politics of America but assume Iran’s mullahs rule a tyranny. Last week’s elections prove otherwise. Here Stratfor describes Iran’s politics and the election’s results. The new leadership team will have to sail through these troubled waters. Iran’s fragile economy is under incredible pressure from the collapse of oil prices — while the military struggle continues for dominance in the region and the agreement with Obama gives Iran new opportunities.

Stratfor, 1 March 2016

Over the weekend, 33 million Iranians went to the polls to vote in historic dual elections, and the results suggest that an important change is underway in Iranian politics. According to the latest reports, the country’s parliamentary elections yielded a rough three-way split among reformists, moderate conservatives and hard-liners. Of the 285 seats up for grabs, 70 will be contested in a runoff vote in April. Meanwhile, the Assembly of Experts elections resulted in a landslide victory for allies of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, as moderate politicians walked away with 15 of Tehran’s 16 district seats.

For Iran’s hard-liners, these results are discouraging. Hard-line politicians lost ground in both the parliament and the Assembly of Experts. Moreover, substantial wins by reformists and pragmatic conservatives in both elections suggest that moderate candidates’ strategy of cooperating across the ideological spectrum has proved successful. But with no guarantee that unity among Iran’s moderate factions will hold once the final votes have been tallied, the outcome says more about what Iranian voters want than about what the newly elected bodies can actually deliver.

Analysis

While Iran’s Interior Ministry has yet to release the official voter turnout, it is no surprise that many polling locations had to extend their hours to accommodate long lines of voters in this round of elections. Iran’s reformist factions, which comprise secular and Islamist politicians promising to adapt to an ever-changing world, typically capture many votes, especially in urban areas. However, these factions boycotted elections in 2004 and 2008 in response to the clerical Guardian Council’s disqualification of hundreds of their peers from the elections. As a result, voter turnout was much lower in both years than it was on Feb. 26.

In the face of potential disqualification and tight controls by the highly conservative Guardian and Expediency councils, Iranian politicians tend to form coalitions and secure endorsements before the elections are held to try to ensure seats. However, these marriages of convenience do not always hold up once the vote is over. Before the reformist-moderate coalition can be considered a newly cemented political force that will lead Iran toward pragmatic change, it is important to consider the issues dividing it and the challenges that lie ahead for the country as a whole.

2009 protest in Iran’s Green revolution, genesis of this victory for the reformers.

High Expectations From Iranian Voters

The latest elections made it clear that much of the Iranian public wants what moderate candidates are offering. For pragmatic conservatives such as Rouhani, this means a healthy economy, safer public spaces for women and better opportunities for international investors; for reformists, it means social liberalization, media freedom and a cautious but assertive foreign policy. But with another round of elections fast approaching in 2017, the candidates voted into office will need to show tangible results quickly if they want to keep public sentiment from souring toward them.

However, effecting change is easier said than done, and a number of obstacles will stand in the newly elected officials’ way. First, economic growth — at least the kind that Rouhani promised during his presidential campaign — will be virtually impossible to bring about. Based on current market conditions, it is unlikely that Iran will be able to boost its oil exports to 2.5 million barrels per day, as Rouhani had hoped. Even if the country managed to raise its exports to a more realistic goal of 0.5 million bpd by the end of 2016 and oil prices rebounded to $40 a barrel, energy revenues would still be far lower than Rouhani could have ever predicted in 2013.

Officials could try to bolster other areas of Iran’s economy, whether through the $7 billion stimulus plan Tehran announced in October 2015 or with the billions of dollars’ worth of manufacturing deals it has signed with European investors. But these efforts may not yield the tangible results Iranians demand quickly enough. Though inflation has declined significantly since Rouhani took office, youth unemployment remains high at around 25 percent. This issue is very important to Iranians, especially the young voters who flocked to the polls in the latest elections and who will undoubtedly return for the 2017 vote.

If Rouhani and his moderate allies fail to deliver the economic progress their constituents are hoping for, they will need to make good on their promised social reforms to keep their momentum ahead of the 2017 presidential vote. But this, too, will be difficult to achieve. The factions within the moderate coalition do not hold the same views on social freedoms. For instance, female lawmakers enjoyed their biggest wins yet during the Feb. 26 elections, but several prominent members on the same moderate ticket as the female victors have adopted conservative stances toward women. In particular, Ali Motahari, who garnered the second-most votes in the Tehran district, has labeled leggings to be detrimental to public space and believes headscarves should be compulsory. Furthermore, Ali Larijani, the powerful speaker of Iran’s parliament, strongly supports Rouhani’s economic policy but has declined to comment on the president’s social liberalization efforts.

Despite the consensus among most moderates and some conservatives that Iran should open up its economy, reformists, pragmatic conservatives and traditionalist conservatives embrace social reform to different degrees. Though young voters demand greater social freedoms for men and women alike, the members of the coalition now ruling the Iranian parliament apparently do not see eye to eye on implementing many of those measures. The same is true of the media freedoms advocated by reformists, which have polarized the moderate conservative factions. It comes as no surprise, then, that Rouhani has been unable (or perhaps unwilling) to follow through with his pledge to release politicians of the banned Green Movement, even though the move would be popular among many Iranians.

In the end, security may be the only realm in which the agendas of all Iran’s political groups fully align. Iran will maintain an active ballistic missile program regardless of whether a hard-liner, reformist or pragmatic conservative government is in place. This program is a critical component of Tehran’s national security strategy, and no political leaders are pushing to dismantle it, despite the fact that it violates certain U.N. sanctions. The country’s nuclear program will be similarly protected, an enduring source of tension between Iran and other members of the international community. Though reformists espouse greater engagement with the West, moderates and conservatives alike stand firmly behind the nuclear program, regardless of what impact it has on the country’s relationships abroad.

Taken together, these points of contention suggest that despite the strong showing moderates had in the latest elections, economic and social change will be slow to follow. Rouhani and his allies have by no means cinched the next presidency. After all, many of the hard-liners who lost in the Feb. 26 elections did not lose by much, and several hard-liners remain popular, especially outside of Iran’s densely populated cities. If Iran’s new leaders cannot fulfill their mandate, and quickly, the tables may turn on them before the next electoral race even begins.

is republished with permission of Stratfor.

No comments:

Post a Comment