Summary: How China wields its growing power will help shape the geopolitical world of the 21st century. Here Stratfor looks at China and speculates at what it might become. {1st of 2 posts today.}

What Kind of Power Will China Become?

Stratfor, 3 February 2016

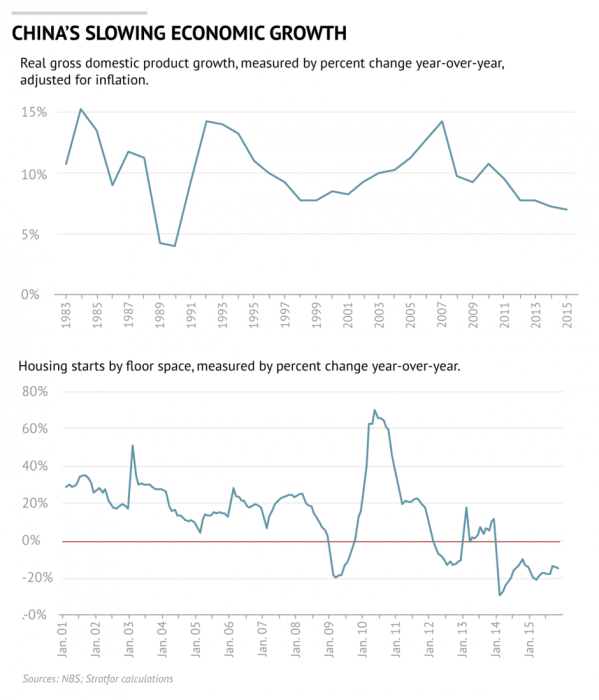

These are grim times for the Chinese economy. In the two years since property markets peaked and subsequently began to slow in most cities across China, it has become abundantly clear that the approach to economic management that sustained double-digit annual growth for two decades has exhausted itself. The unprecedented stock market volatility of the past year, along with signs of spreading unemployment and labor unrest in many regions, are important reminders that the transition to new foundations of national economic growth will in all likelihood be bitter, slow and unnervingly uncertain.

These are grim times for the Chinese economy. In the two years since property markets peaked and subsequently began to slow in most cities across China, it has become abundantly clear that the approach to economic management that sustained double-digit annual growth for two decades has exhausted itself. The unprecedented stock market volatility of the past year, along with signs of spreading unemployment and labor unrest in many regions, are important reminders that the transition to new foundations of national economic growth will in all likelihood be bitter, slow and unnervingly uncertain.

In times like these, it is tempting to embrace visions of irreversible decline — just as it was easy, in the expansive years of consistently high growth, to view China’s rise as straightforward and inevitable. As Stratfor pointed out well before the 2008-09 global financial crisis, which set in motion many of the policies and processes that underlie China’s current woes, the only certainty in the high-growth years was that they would someday end. Their ending, we predicted, would unleash tremendous and potentially destabilizing social pressures long kept at bay by the promise of universal employment and rising material prosperity. At the least, this process would slow China’s political, military and economic rise as the decade ends. At worst, it would send China into a more debilitating and longer-lasting period of crisis and fragmentation.

It is crucial to remember that international politics, defined as it is by the rise and fall of great powers, follows rhythms very different from and often far slower than those of international markets and media. The rise of great powers is never a clear-cut process, as the vicissitudes of European politics from the Treaty of Westphalia to the Paris Peace Conference make clear. Even for the United States — as inevitable a modern great power as any — the path to international pre-eminence was pockmarked by numerous economic crises and profound domestic social and political tension.

It is crucial to remember that international politics, defined as it is by the rise and fall of great powers, follows rhythms very different from and often far slower than those of international markets and media. The rise of great powers is never a clear-cut process, as the vicissitudes of European politics from the Treaty of Westphalia to the Paris Peace Conference make clear. Even for the United States — as inevitable a modern great power as any — the path to international pre-eminence was pockmarked by numerous economic crises and profound domestic social and political tension.

In this installment in our occasional series on China’s evolving role in and relationship to the international system, we step back and look at China’s trajectory in the early 21st century. While we can anticipate with some certainty that the coming years will be difficult for China’s economy and political system, the question remains: What kind of power will China be if and when it emerges on the other side of its current troubles? After all, there are many reasons to expect that in 10 or 15 years, China will be a greater, not a lesser, power than it is today: It has the world’s largest (and still growing) consumer market, an increasingly urbanized and educated workforce more than twice the size of the United States’ total population, an industrial sector pushing ever closer to the world technological frontier, a large (if insufficient) domestic natural resource base, and powerful and sophisticated governing institutions.

What Kind of Great Power?

The question is what kind of great power China will be. Will it become, to use Henry Kissinger’s term, a revolutionary power bent on overturning the regional and global political status quo? Will it be forced by the systemic uncertainty of an anarchic international order to go on the offensive in maximizing its share of world power — a process that, as the political scientist John J. Mearsheimer argues, will inevitably bring it into conflict with the United States? Or will China, as many in the tradition of “defensive realism” rooted in the ideas of Kenneth Waltz argue, strive only for enough power to ensure adequate security and thereafter adopt a defensive stance? Needless to say, how we answer these questions will in large part determine how we view the future of international politics, in East Asia and globally.

The aim of this essay is not to provide a definitive judgment on China’s trajectory but rather to weigh the forces — both material and ideological — that will shape how China’s leaders view and act within their evolving geopolitical environment. To gather clues to the kind of power China might become, we first look to China’s past — to the Sinocentric world order over which it predominated until the mid-19th century and to the strategies with which successive dynasties built and maintained that order. Having established the kind of power China was before its entry into the modern international system, we can better judge whether and to what extent the worldview and strategies adopted by its dynastic rulers can function in a world characterized by very different pressures, both systemic and domestic.

The Sinocentric World Order

China is unique among historical great powers in having presided over a legitimate and remarkably stable regional order for nearly two millennia. If the defining features of modern international politics are the persistence of anarchy — that is, absence of world government — and the dynamic of “balance of power” generated by this anarchy, then the Chinese dynastic world order was marked, first and foremost, by strong elements of anarchy’s structural obverse: hierarchy.

Thanks in large part to its overwhelming demographic heft, its technological and bureaucratic sophistication, and often but not always its military superiority, China was the unquestioned center of gravity in East Asia for most of the period from 221 B.C. to A.D. 1842. This material superabundance relative to that of other regional powers was, in turn, powerfully reinforced by the pull of China’s civilizational pre-eminence. So great was China’s power and influence relative to all other premodern East Asian polities that even when invaded by outsiders — such as the Mongols in 1271, the Manchu in 1644 and, unsuccessfully, the Japanese in 1592 — China remained central. Beijing, not the ancestral lands of Genghis Khan or of the Manchurian leader Nurhaci, served as the political capital for the Yuan and Qing dynasties.

In Western Europe, the relative parity in economic and military power among Spain, Britain, Austria, France and later Germany ultimately gave way to an international system grounded in the formal equality and mutually recognized sovereignty of independent nation-states. By contrast, Sinocentric East Asia was formally unequal, with the autonomy of lesser states (especially those closest, culturally and geographically, to China) often contingent on their acceptance of Chinese supremacy.

Just as Confucianism, the dominant political philosophy in dynastic China, envisioned domestic society as a more or less rigid hierarchy of asymmetric social roles — emperor and vassal, husband and wife, father and son — so China’s rulers saw themselves as sitting at the apex of a world order (tianxia, literally “all under heaven”), in which non-Chinese states were merely extensions of the emperor’s heavenly mandate. That China viewed its world and external relations not in terms of anarchy and sovereign competition but of hierarchy and filial harmony is most clearly seen in the system of “tribute” through which it managed interstate trade. Growing out of an earlier program of direct taxes on defeated neighboring polities, the tribute system imagined international trade as simply the exchange of gifts between the emperor, as world sovereign, and his many kingly vassals.

What is most striking about this highly inegalitarian order, from the perspective of modern world politics, is how persuasive and stable it proved. To be sure, China’s history is littered with war and devastation. But most of this devastation resulted from internal political upheaval and civil war, not from foreign invasion.

Likewise, it must be emphasized that in periods of dynastic decline within China, tributary relations — and the acknowledgement of Chinese supremacy that underpinned them — often became mere glosses on what was, in substance, international trade among autonomous states. Even so, the periodic superficiality of China’s regional authority notwithstanding, it is noteworthy that for hundreds of years, non-Chinese states conducted their business with China as well as independent of China in the language and terms of the Sinocentric tribute system. The historical record suggests that for long periods, the states of Korea and Vietnam, and to a lesser extent Japan and polities in Central and Southeast Asia, often accepted, however grudgingly, their place as subordinate cogs in a Sinocentric order.

All of which begs the question: How did successive dynasties maintain the coherence and stability of the Chinese world order?

The overwhelming impression given by the bulk of historical scholarship on pre-modern China’s foreign relations, as well as by official dynastic histories, is that generally the Chinese empire sustained its regional pre-eminence through civilizational and economic “soft power,” while adopting a defensive military posture and conservative grand strategy. Rather than move aggressively to expand control over neighboring states, this traditional interpretation holds that the Chinese empire sustained its pride of place primarily through its civilizational and commercial pull.

Sheer demographic and economic size made China an invaluable market for foreign traders, access to which was contingent on the recognition of China’s primacy. Meanwhile, its sophisticated bureaucratic and philosophical-literary traditions naturally made China a model to be emulated by smaller, weaker states. Together, these advantages meant that China only rarely had to resort to force to secure its interests — and then only to rectify morally degraded, illegitimate or renegade regimes. Not surprisingly, this interpretation coheres closely with Confucianism’s systematic denigration of military aggression and celebration of the more “pacific” arts of the civilian scholar-official.

However, alongside Confucian China’s peaceful and defensive orientation ran another strand of decidedly more assertive strategic behavior. Consider, for example, several episodes in the external relations of Ming China, the last Chinese-ruled dynasty and by most accounts one of the most consciously Confucian of China’s imperial houses. In the century and a half after coming to power, Ming China invaded and annexed Vietnam, led a series of large-scale punitive campaigns deep into inner Asia to pre-empt any future threats to its northern border, and launched several waves of “treasure fleets” throughout Southeast and South Asia in calculated and often openly coercive displays of Chinese military might. On at least three occasions, these fleets — loaded with upward of 27,000 soldiers — were used to forcibly remove local kings perceived to have disobeyed Ming authority.

Such assertions of military and political might are by no means unique to the Ming. Nor was it China’s most expansive dynasty, militarily speaking. Indeed, Ming China is perhaps best known for building the current Great Wall — that potent symbol of traditional China’s purportedly defensive and stabilizing strategic posture. It would be wrong to deny that for much of its history — especially but not only during times of relative military weakness or dynastic decline — China has behaved defensively, working to bolster the status quo rather than to destabilize it. After all, China never seriously sought to expand far beyond what are today its recognized borders, despite manifold opportunities to do so. Nonetheless, it is clear that despite successive dynasties’ efforts to write pacifism and “virtue” into China’s foreign relations, China has often — especially during times of military and political dominance over neighboring states — behaved in ways that belie its pacifist self-image.

From Sinocentrism to Chinese Exceptionalism

It is possible, but not likely, that these twin legacies — the conservative and defensive versus the assertive and expansive — will have no bearing on China’s foreign policy in years to come, as the country’s deepening global economic integration and expanding international interests compel it to adopt a more proactive diplomatic and military posture. Material capabilities, combined with the disposing and constraining forces of the international system, may be the key determinants of whether a great power is more or less active on the world stage. But while these factors tell us what kinds of pressures great powers face and give us some sense of how able they are to overcome those pressures, they do not tell us the means by which great powers will strive to do so. Ideas about the world matter: They shape how political and military elite filter, interpret and make sense of the ever-shifting inputs on which they base their decisions. In a country as intensely aware of its own oracular history as China, the effect of inherited ideas on contemporary foreign policy cannot be discounted.

It is possible, but not likely, that these twin legacies — the conservative and defensive versus the assertive and expansive — will have no bearing on China’s foreign policy in years to come, as the country’s deepening global economic integration and expanding international interests compel it to adopt a more proactive diplomatic and military posture. Material capabilities, combined with the disposing and constraining forces of the international system, may be the key determinants of whether a great power is more or less active on the world stage. But while these factors tell us what kinds of pressures great powers face and give us some sense of how able they are to overcome those pressures, they do not tell us the means by which great powers will strive to do so. Ideas about the world matter: They shape how political and military elite filter, interpret and make sense of the ever-shifting inputs on which they base their decisions. In a country as intensely aware of its own oracular history as China, the effect of inherited ideas on contemporary foreign policy cannot be discounted.

With this in mind, it is worth noting the emergence in recent years of an active, if still somewhat nascent, discourse of exceptionalism among Chinese policy elite. Invocations of China’s “difference” and “singularity” (to use Kissinger’s term) move in multiple directions, sometimes referring to the incomparable magnitude of China’s domestic economic challenges or the uniqueness of its particular social and political fissures. More often than not, however, and especially when evoked by Chinese leaders, this sense of exceptionalism is explicitly tied to the notion of China’s peaceful rise. More pointedly, it is drawn on to express the idea that China, thanks to its legacy as a benign and inclusive rather than aggressively expansionist hegemon in pre-modern East Asia, will not seek, as so many other modern great powers have, to remake the status quo in its own favor. China, they contend, is an exception to the modern international rule that as great powers rise, they invariably seek to impose their will on the international system, as well as on the individual states that compose it.

Whether China’s future leaders can make good on this promise remains to be seen. The fact is that until relatively recently, China has lacked the sort of thickly interwoven international interests and dependencies that might necessitate a more far-reaching, assertive foreign policy. More to the point, it has lacked the military capabilities and political wherewithal to act to protect, in any systematic manner, its international interests. On both fronts, this is beginning to change. So, too, is China’s understanding of its external interests and responsibilities, at least as reflected in recent moves to assert its territorial claims in the South and East China seas and early efforts to built blue water-capable naval forces.

But even if China’s long history of defensive and status quo-promoting behavior fails to preclude it from acting like a more conventional great power in the years to come, this does not, in itself, render that legacy meaningless. In this respect, it is instructive to consider the role that ideas have played in shaping the foreign policy of another heir to a vivid exceptionalist discourse: the United States. Far from a mere cover for power-political interests, the idea of the United States as exceptional — whether as an exemplar for other countries or as an active agent in the spread of democracy worldwide — has played an important role in shaping how the nation wielded material resources.

As China’s wealth and military power grow, as they likely will in the long run, the anarchic structure of the international system will push China to use this power to improve its security and the safety of its increasingly far-flung interests and assets. The question is not whether China will be forced to respond to these systemic pressures, but how it will attempt to adapt the lessons of its history to cope with the risks and uncertainties of a very different kind of world order from that it so long dominated.

No comments:

Post a Comment