9 December 2015

Military strategist, classical scholar, cattle rancher – and an adviser to presidents, prime ministers, and the Dalai Lama. Just who is Edward Luttwak? And why do very powerful people pay vast sums for his advice?

Military strategist, classical scholar, cattle rancher – and an adviser to presidents, prime ministers, and the Dalai Lama. Just who is Edward Luttwak? And why do very powerful people pay vast sums for his advice?

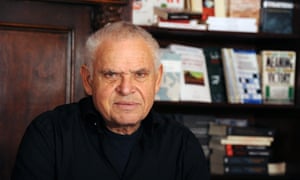

Edward Luttwak earns $1m a year advising governments and writing books. Photograph: Jocelyn Augustino/Commissioned for The Guardian

People contact Edward Luttwak with unusual requests. The prime minister of Kazakhstan wants to find a way to remove ethnic Russians from a city on his northern border; a major Asian government wants a plan to train its new intelligence services; an Italian chemical company wants help settling an asbestos lawsuit with a local commune; a citizens’ group in Tonga wants to scare away Japanese dolphin poachers from its shores; the London Review of Books wants a piece on the Armenian genocide; a woman is having a custody battle over her children in Washington DC – can Luttwak “reason” with her husband? And that is just in the last 12 months.

Luttwak is a self-proclaimed “grand strategist”, who makes a healthy living dispensing his insights around the globe. He believes that the guiding principles of the market are antithetical to what he calls “the logic of strategy”, which usually involves doing the least efficient thing possible in order to gain the upper hand over your enemy by confusing them. If your tank battalion has the choice of a good highway or a bad road, take the bad road, says Luttwak. If you can divide your fighter squadrons onto two aircraft carriers instead of one, then waste the fuel and do it. And if two of your enemies are squaring off in Syria, sit back and toast your good fortune.

Read more Luttwak believes that the logic of strategy contains truths that apply to all times and places. His books and articles have devoted followings among academics, journalists, businessmen, military officers and prime ministers. His 1987 book Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace is a set text at universities and military academies across the world. His official – and unofficial – advisory work for the US government has been praised by generals and secretaries of state. He is a familiar figure at government ministries, in the pages of leading journals and on Italian television.

But his work is not limited to armchair theorising. Readers who have been treated to Luttwak’s counterintuitive provocations on the op-ed page of the New York Times might be surprised to know that he considers writing an extra-curricular activity. For the past 30 years, Luttwak has run his own strategic consultancy – a sort of one-man security firm – that provides bespoke “solutions” to some very intractable problems. In his long career, Luttwak has been asked by the president of Mexico to help eliminate a street gang that was burning tourist buses in the city of Mexicali; the Dalai Lama has consulted him about relations with China, European governments have hired him to root out al-Qaida operatives, and the US army has commissioned him to update its counterinsurgency manual. He earns around $1m a year from his “jobs”. “It’s always important to get paid,” he likes to insist. “It protects you from the liberal problem of good intentions and from being called an intriguer.”

It is tempting to imagine Luttwak as a man exiled to the wrong place and time, whose fate, like a character in Nabokov, has been reduced from old-world brilliance to something less grand in 21st-century America. It is not hard, after all, to picture him conniving at the Congress of Vienna, or plotting murders in the Medici court. He has the air of the seasoned counsellor to the prince who is dispatched to deal with the Mongols and returns alone, on horseback, clutching advantageous terms on parchment.

But only in America was the career of Edward Luttwak possible. The perpetually renewable reservoir of naivety at the highest levels of the US government has been good for business. During the cold war, Luttwak was often identified as a peculiar American species known as the “defence intellectual”. These were academics who served power, who were often impatient with democratic procedure, and who enraptured audiences – from thinktanks to military academies – with their elaborate projector-slide frescoes of nuclear apocalypse.

When he testified before Congress in the 1980s, Luttwak seemed to be the latest heir in the line of saturnine visionaries – from Herman Kahn to Henry Kissinger – who were sure about which way the world was going. “Most defence intellectuals are three-fourths defence and one-fourth intellectual,” says Leon Wieseltier, the Washington fixture and literary impresario, who first met Luttwak during the Reagan years. “But Edward was this figure out of a Werner Herzog film. He was not some person who had read a bit of Tacitus and now worked at the Pentagon. He knew all the languages, the geographies, the cultures, the histories. He is the most bizarre humanist I have ever met.”

Outside of Washington, Luttwak is best known for his writing. His reputation still rests on his 1968 book Coup d’Etat: A Practical Guide, published when Luttwak was 26. It is a tongue-in-cheek pastiche of a military manual that he wrote while working as an oil consultant in London. The book explains in clinical detail how to seize power in various types of states. It comes with elaborate charts and a typology of victorious communiques (“the Romantic/Lyrical”, “the Messianic”, “the Unprepared”) drawn from successful African coups.

The book was praised by John le Carré and warmly reviewed by critics on the left and the right. “One suspects that, like Machiavelli himself, he enjoys truth not only because it is true but also because it shocks the naive,” wrote Eric Hobsbawm. But for Luttwak the best notice came in 1972, when General Mohammad Oufkir was assassinated during an attempted coup against King Hassan in Morocco; it was rumoured, to Luttwak’s delight, that a blood-spattered copy of Coup d’Etat was found on the general’s corpse.

Luttwak is less a grand political theorist in the tradition of Machiavelli or Hobbes than a skilled bricoleur of historical strategic insights. But he is sometimes mentioned in the same breath as legendary military strategists. “He’s a hell of a lot smarter than Clausewitz,” says Merrill McPeak, the former chief of staff of the US air force, who sought Luttwak’s advice in 1990 while planning the bombing of Iraq during the first Gulf war. “His main asset is just knowing more than everyone else.” Other acquaintances are more circumspect. “When I think of Ed Luttwak,” Zbigniew Brzezinski, who served as national security adviser to president Jimmy Carter, told me, “I think of a strong intellectual, inclined towards categorical assertions, penetrating in many of their insights, but occasionally undermined by the desire to have a shock effect on listeners. Nonetheless, he’s almost always worth listening to.”

In a world where almost every national government now makes use of “strategic consultants”, Luttwak’s services have only increased in value. The rise of a governing culture that does its best to mimic the “best practices” of the business world has been of great benefit to his business. The peculiar type of counter-intuition he offers seems to have never been more in demand. His provocative public persona only contributes to the sense, among the many world leaders, military commanders and others who purchase his services, that with Luttwak they are not dealing with a business school graduate tapping into a database, but something more deliciously old-fashioned. Luttwak sweats savoir faire. He projects the image of a wise man in intimate contact with a deeper, hidden level of reality. Listening to Luttwak discuss his clients, one has the impression that he is passed around from government to government like some pleasurable, illicit stimulant.

One has the impression that he is passed around from government to government like some pleasurable, illicit stimulant But what makes Luttwak unusual is the fact that so many powerful people hire him in the first place. What does a 72-year-old Romanian emigre in the Washington suburbs provide that they cannot get elsewhere?

Outside Luttwak’s house in Chevy Chase, Maryland, stands a tall metal statue of the would-be Hitler assassin Claus von Stauffenberg; a large wooden totem of Nietzsche stares out from a bay window. When I visited this spring, a helmeted figure appeared to be assembling something with industrial welding equipment through a basement window. The figure was Luttwak’s elegant wife, Dalya, who greeted me at the door while Luttwak finished shearing the bushes outside. “I do sometimes worry that when I see a car moving slowly outside the house that someone has finally come to finish us off,” she said. Dalya was preparing for a show in New York City, and the floor of her sculpture studio was strewn with tools and the steel rods she shapes into giant root-like structures.

Luttwak first came to Washington in 1969. After graduating from LSE, he followed his roommate Richard Perle – the neoconservative eminence grise and adviser to Ronald Reagan and George W Bush, known in the press as the “Prince of Darkness” – to work for a cold war thinktank called the Committee to Maintain a Prudence Defense Policy. Chaired by the former US secretary of state Dean Acheson, the committee was dedicated to wrapping rabid strategic proposals in the language of security and necessity. Luttwak now finds Washington to be a “pleasantly innocuous” town, but he hated it when he first arrived: “I remember going to Kissinger’s favourite restaurant, Sans Souci, and eating food that would have been rejected by Italian PoWs.”

Luttwak could never fully bend to the orthodoxies of the Beltway. “He has a way of thinking outside of the box, but it’s so far outside of the box that you have to put a filter on it,” says Paul Wolfowitz, another Iraq war architect who was also a member of Acheson’s committee. “If you had asked Edward if he would have liked to be secretary of state, he would not have said no,” says Perle, “but he didn’t want to rise as a bureaucrat. He wanted access to power without going up ladders.” Luttwak’s relations with both men have cooled in recent decades. “In Washington you are considered frivolous if you write books,” he said. “Wolfowitz and Perle were always supposed to be writing these great works, but they never did. I was considered unserious for knowing things.”

Today, Luttwak’s home office contains the better part of the Loeb classical library on its shelves, interspersed ostentatiously with helmets, pistols and stray pieces of artillery. A certificate congratulating him for his contribution to the design of the Israeli Merkava tank rests above a photo of his daughter, a former Israeli soldier, driving the same tank. Luttwak spends much of his time at the computer. He follows the news closely and interprets it as an ongoing comedy. At the time of my visit, Yemen’s Houthi insurgents had just invaded the port city of Aden. “It’s as if Scottish Highlanders were walking around with guns in Mayfair,” he said.

“You know, I never gave George W Bush enough credit for what he’s done in the Middle East,” Luttwak continued. “I failed to appreciate at the time that he was a strategic genius far beyond Bismarck. He ignited a religious war between Shi’ites and Sunnis that will occupy the region for the next 1,000 years. It was a pure stroke of brilliance!”

Luttwak at home in Maryland in front of some of the books he has written and translated. Photograph: Jocelyn Augustino for the Guardian Luttwak is square-jawed and has a close crew cut of grey hair. He is in remarkably good shape for a man in his 70s, which he attributes to a new sugarless diet. He has a mild, Mitteleuropean accent, which he supplements with a wide repertoire of gestures that call to mind the movements of an embattled crab: the fey flick of the index finger, the four-fingered pinch-of-salt jab, the fist-grenade that periodically explodes at chest level to punctuate a point.

He is the sort of man who is not satisfied with simply making an impression; he wants to mark his listener for life. As we walked through the house, he pulled 15th-century Byzantine-bound manuscripts, which he treats like paperbacks, from the shelves. He started to simmer every time Dalya took the reins of the conversation. “She started out so promisingly,” he said as we reviewed her sculptures. “I met her when she was a 19-year-old Israeli prison guard, and she’s the best driver of a Jeep I know.” Next to the sculptures was a giant welding machine. “It’s illegal to have that in a residential area,” he said.

After we entered his office, Luttwak became momentarily absorbed by a YouTube video of a gaur, the largest bovine on earth. A young Yorkshire filmmaker appeared in the side of the frame. “It’s a wild Indian gaur,” he frantically whispered into the camera, “Every now and then it looks at me … But if I get any closer he might get really annoyed so I’m going to be very careful.”

Luttwak jabbed childishly at the screen, emitting his standard derisive guttural – “Ah! Ah! Ah!” – and pointed to his desktop background, a picture of himself feeding and petting an enormous gaur in the Indian state of Nagaland. “I have an acute interest in bovines,” he said with an impish smile. He went back to typing on his computer, pecking sharply at the keyboard. For a moment, I thought I could see a gun strap through his T-shirt, but it turned out to be the white braces that Luttwak always wears. “I was born without a bottom,” he explained, a bit mournfully.

“The cow is the most complex machine on Earth,” Luttwak told me when I met him one morning in February, at El Trompillo airport in Santa Cruz, the largest and wealthiest city in Bolivia. “It converts cellulose into bone, meat and hoof. My cows are closer to gazelles. You will see how they leap and jump. We are not like American farmers. We don’t give them drugs and the alfalfa that makes them sick in order to get marbled meat. And we don’t kill them early. Indians worship cows because of the way they congregate at the edge of the river in the evening. It is an undeniably mystical thing and it makes sense to worship it.”

Luttwak first set his sights on Bolivia in 1998, when he convinced three wealthy partners that a recently signed South American free-trade agreement would make Bolivian land on the Brazilian border as valuable as that of its richer neighbour. Together they bought 19,000 hectares in a north-eastern province known as the Beni. Luttwak went on to buy cattle to graze the land. He now owns a herd of 3,000.

An expert who can explain the ballistic capabilities of a Tomahawk missile to a prime minister is one thing; but a man who can also debate bull-rearing methods with a hardened Bolivian cowboys in natural latex ponchos is something else. The combination of scholarly prowess and machismo is a much sought-after alloy in many high offices of the world, where extreme masculinity is still the coin of the realm. (In moments that threaten to be dull, Luttwak makes a habit of looking around for lethal objects. “This chopstick is perfect, for instance,” he told me later at a hotel restaurant. “But you must remember to thrust it deep enough into the eye socket so that it punctures the frontal cortex.”)

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Edward Luttwak with Bolivian cowboys dressed in their natural latex ponchos. Photograph: Thomas Meaney The Beni is a stubbornly defiant place of dense jungle and lowland plains that make it vulnerable to severe flooding. “You can’t do anything without danger in the Beni,” said Luttwak as we waited to board the hour-long turbo-prop flight north to the regional capital of Trinidad, the first stop on our way to Luttwak’s farm. “The people are the true macho. Not the fake macho of Argentina and Texas. A wife in the Beni thinks nothing of knocking a jaguar out with a frying pan. A man will casually mention that he lost a finger that morning, but no bother.” There are also several thousand Mennonite farmers in the Beni – descendents of German-speaking anabaptists exiled from Russia – whose antiquated farming techniques and pioneer grit Luttwak particularly admires.

In the Beni, politics belongs to the narco traffickers who work the border with Brazil, the new urban business class of the cities, and the cattlemen of the plains. It was one of the most powerful of these cattlemen, Winston Rodriguez Araya, that Luttwak had come to see. The previous year, Don Winston, as Luttwak calls him, lost hundreds of cattle to flooding, and had made arrangements to rent Luttwak’s herd to replenish his own. But a misunderstanding had arisen. Don Winston had delayed returning the animals to Luttwak. Luttwak was coming to get his cows back.

After landing in Trinidad, we drove six hours further north, deeper into the Amazon basin, to San Joaquin, the closest town to Luttwak’s farm. There were matters requiring immediate attention when we arrived. News of the terrorist attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo had broken when Luttwak landed in Bolivia, and the last TV reports we had seen had included grainy footage of the gunmen. “It was done with AK-47s, which are very hard to get a hold of in Paris,” Luttwak kept insisting during the long drive, though we knew almost nothing about the attacks. “In Poland you can get new AK-47s complete with the little oil canister for $800, but they are nearly impossible to get in Paris. These people have connections.”

Luttwak wanted to write a piece about the future of Muslims in Europe. True to form, he wanted to infuriate liberals with the argument that western leaders, with their “fairytale collegiate view” of Islam, were in fact betraying the hard-working parents from the Middle East and Africa who had immigrated to the US and Europe in order to save their children from Islam. But there was no internet in town. We drove to the local military outpost. Luttwak entered the headquarters of the newly stationed commander and introduced himself. There was no internet. The colonel explained that in the Beni the army mostly concerns itself with protecting people from floods. “The problem is of course predicting when the floods will happen,” he said. “If you had the internet,” replied Luttwak, “that might be less of a problem.”

The soldier at the checkpoint of the camp asked about the white letters on Luttwak’s blue cap. He was wearing a NYPD cap – in “solidarity”, he said, with US police after the killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. “I would really enjoy wearing this on a stroll through Manhattan,” he told me. “The great stupidity of the Michael Brown trial was that they announced the verdict late at night, which was begging for riots. They should have announced it early the next morning when they could have been more prepared.”

Later that day, after an exchange of greetings and gifts at the home of Luttwak’s trusted friends and business partners Don and Donna Mandy, local ranchers who live in a red adobe Jesuit house off San Joaquin’s main square, Luttwak and I huddled into their bedroom, where the Paris attacks followed reports on local political corruption and the weather as the fourth item on the Bolivian nightly news. Armed with these findings, Luttwak retired to the dining table, and wrote his dispatch in less than two hours. (When we reconnected to the internet three days later, he sent off the article. A few days after that, it appeared on the home page of Le Monde.)

Donna Mandy then prepared a dinner of paku fish and maize cakes, followed by a round of the Bolivian spirit singani, which Luttwak barely touched. Sitting at the table, he examined the medical instructions that came with the growth hormone tablets that Don Mandy’s son, Alex Martinez, had set aside for his two adolescent daughters (they were healthy, but he wanted them to be taller). Stretching out the tiny paper of medical instructions like an accordion, Luttwak quickly reached a verdict. “Alex, you cannot give these drugs to the girls. The chance of cancer is too great. The effects of the growth protein is just too risky.” This was Luttwak’s specialism on display: the sudden flex of expertise, the pinpoint detail lanced across the room.

There is a passage in his 2009 book The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire where Luttwak shows off this skill to the extreme. He digresses for 14 pages about the special weapon used across ancient central Asia called the “composite-reflex bow” – which he believes unlocks one of the mysteries of Homer’s Odyssey. When Odysseus returns home to Ithaca to kill the suitors who have designs on his wife, he shoots them with a bow that none of them have been able to use out of what would appear to be a lack of strength. But Luttwak identifies it as a composite reflex bow that Odysseus presumably picked up on his foreign travels, and which only he knows how to string properly:

“The Ithaca provincials had tried to string the bow with brute strength, by forcing it to curve enough to receive the string – easy to do if one has at least three hands, two to pull back the limbs into position, one to tie or loop the string on each ear – but impossible to do with only two. Odysseus knew how to string reflex bows such as his own.”

Translate this kind of scholarly detail into other areas – Indian national security, the Argentinian air force, Iraqi ground targets – and you can see the source of appeal in receiving a memo from Luttwak. If Luttwak had been present at the crucifixion of Christ, he would have begun his report with a note on the type of nails that were used. He brings literary flourish to fields that would seem the most resistant to them. The performance is partly contained in the rhetoric: in order to understand the Odyssey, you cannot go to museums, or consult academic commentaries, or trust your own judgment – instead you must go to Luttwak.

If Luttwak had been present at the crucifixion of Christ, he would have noted the type of nails that were used Luttwak’s idiosyncratic historical work often commands respect from academic experts. “Edward broke open a new academic field about the Roman frontier,” the eminent classicist GW Bowersock told me, referring to Luttwak’s book The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire, which began life as his Johns Hopkins political science dissertation. “What makes him a great scholar is that his practical work and his scholarship constantly nourish each other.” Bowersock is right, but there is an additional element. If there is one thing that separates Luttwak from other writers on strategy it is not only his ability to move between typically disconnected realms, but also his way of flattering the customer: he can make a head of state feel like an intellectual, the academic feel like a man of action, and the Bolivian rancher that they are in the presence of a man with terrifyingly powerful connections.

Luttwak has written 14 other books, ranging from studies of American capitalism to the Israeli Army. Kazakhstan: An Alphabetic Guide – drawn from the notes for a recent consultancy project for the country – will appear as soon as it is cleared by Kazakhstani censors. Another study, tentatively entitled The Marriage of Genghis Khan and Anna Karenina – about the way vast distances have determined Russian forms of rule – is currently under way. Luttwak is perhaps even better known for his journalistic insurgencies. For Prospect magazine, he once argued that the Middle East had no strategic importance and its “backward societies” should be ignored; in the New York Times, he advised savouring the onset of war in Syria, since America’s sworn enemies were fighting each other.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Luttwak with some of the 3,000 cattle he owns in Bolivia. Photograph: Thomas Meaney The morning after our dinner at Don and Donna Mandy’s, we drove out to Luttwak’s farm for a cattle roundup. Into two giant troughs, we dumped bags of salt that summoned the herd. “These are Indian cattle – the Portuguese brought them here from Goa,” said Luttwak, as the cows approached. “They are not stupid. They instinctively sense that eventually we want to kill them.” Dozens of cattle were now in a circle around Luttwak. He was elated. He massaged their heads, he whispered to them, but just as quickly he seemed to grow bored with them, as if disappointed that they had nothing to say.

Luttwak’s earliest memory is of being carried, aged three, on the shoulders of a Red Army soldier who was billeted at his parents’ villa in the region of Romania known as the Banat, where his father was a prominent merchant. Though the Banat was close to the epicentre of the second world war, it was never directly occupied by the Germans. Luttwak grew up speaking Romanian, Vlach and French, but his mother tongue, as was common among the Jewish population of the region, was German. He remembers his parents as courageous: “They were the sort of people who, if they saw water they liked, dove in without checking the depth.”

Yet it was the Russians, not the Germans, who posed the greater threat to the Luttwaks as the war came to a close. As a businessman with capital, Luttwak’s father stood to lose everything. The family shipped itself south in Luttwak & Co box cars and boarded one of the last ferries to Sicily, where Luttwak’s father entered the orange export business, and successfully warded off the local mafia.

After Sicily, the Luttwaks moved to Milan, where Edward was miserable and got into fights at school. The magical childhood in Palermo had been abruptly replaced by adolescence in a city that celebrated stolidly efficient industrialists. “There was nowhere to play. The parks were a disgrace. I lost all my friends from Palermo. I found myself amid a bunch of very bourgeois kids,” Luttwak once told the intellectual historian Corey Robin. Luttwak’s parents decided to send him away to a Jewish boarding school, Carmel College, in Oxfordshire. (He got into fights at Carmel too, “but the English had a different attitude toward fighting; they not only tolerated it, but respected you if you held your own.”)

In 1957, at the age of 15, he quit school, temporarily cut off contacts with his parents, and moved to London, where he worked in a teashop in Piccadilly and enlisted in the Honourable Artillery Company, a territorial regiment quartered in London. Luttwak claims to have first seen military action in 1958, as 16-year-old in the jungles of North Borneo, where a small British force was sent in a clandestine operation to prop up the native Dayaks against Chinese communists. But then, according to Luttwak, the world would be a very different place without him: he claims a significant hand in a large proportion of the most momentous events of the postwar era: from the decision to throw molotov cocktails at Soviet tanks in the Prague Spring, to Iran’s 1981 release of American hostages, to the existence of the Toyota Prius.

Luttwak’s talent for mythomania relies on his sensual appetite for detail, but it also gestures towards something beyond it. He tirelessly buffs the edges of his own legend; he is competitively interesting. When confronted by anyone who threatens to second-guess him, Luttwak responds either by burying them in a welter of technical detail, or crushing them with timeless, prophetic generalities. The result is that he is nearly invincible in conversation. Everything he has ever read or heard is ready for rapid deployment.

Luttwak’s antagonisms, charms, and provocations are also a way for him to ward off his greatest fear: boredom. During the eight days I spent with him, in moments where nothing was happening, or when the focus of a conversation momentarily deserted him, Luttwak appeared almost in pain. But his war on boredom is more than a personal crusade. His mortal enemies are those who wish to rationalise the world, who want to make militaries and states and intelligence agencies run like businesses. This puts him at odds with many of the American conservatives who have, over the years, been his chief patrons in the form of thinktanks and military contractors. “I believe that one ought to have only as much market efficiency as one needs,” Luttwak told Robin. “Because everything that we value in human life is within the realm of inefficiency – love, family, attachment, community, culture, old habits, comfortable old shoes.”

Luttwak’s antagonisms, charms, and provocations are also a way for him to ward off his greatest fear: boredom. During the eight days I spent with him, in moments where nothing was happening, or when the focus of a conversation momentarily deserted him, Luttwak appeared almost in pain. But his war on boredom is more than a personal crusade. His mortal enemies are those who wish to rationalise the world, who want to make militaries and states and intelligence agencies run like businesses. This puts him at odds with many of the American conservatives who have, over the years, been his chief patrons in the form of thinktanks and military contractors. “I believe that one ought to have only as much market efficiency as one needs,” Luttwak told Robin. “Because everything that we value in human life is within the realm of inefficiency – love, family, attachment, community, culture, old habits, comfortable old shoes.”

The Luttwak family in Palermo when Edward was a small child Photograph: Edward Luttwak For Luttwak, capitalism is synonymous with boring adulthood: ledgers, marginal returns and the expectation that the world will fundamentally remain the same. As a strategist, Luttwak sees the presumption of predictability as a damning vulnerability. As a historian of the ancient world, he is too alive to the prospect of civilisational ruin to put any faith in the idea that capitalism contains its own solution. Now that he is rich, making money for Luttwak has become a kind of pastime, and raising cattle is his attempt to make it in the least dreary, most archaic way possible. More and more it seemed we had come to the Amazon to provide Luttwak with another chance to “raise a thirst”, and it was understood that I was there to experience an endangered sanctuary based on values such as honour and daring, in which Luttwak prowled around as a Homeric hero. “Take as many pictures as possible,” he repeatedly told me. “Note everything down.”

On our third day in the Amazon, we drove out to check on the cattle that Luttwak had lent to Don Winston. There were traces of Don Winston’s empire – dairies, cattle, tenant farms – along the road for miles before we arrived at the ranch. “The man has more land than Belgium,” Luttwak said. His elaborate descriptions of Don Winston’s past exploits as a local kingpin had the effect, presumably intended, of making me slightly wary of meeting him.

Cowboys were rounding up the herd as we pulled up to the estate. Outside a white McMansion in a field of bright green, encircled by corrals, Don Winston ambled into vision: black slab of hair flattened back, obligatory moustache, shirt unbuttoned almost all the way in the Beni style, revealing a generous triangle of cured flesh.

Luttwak’s negotiations with Don Winston started around a small kitchen table with Nescafes and farm milk. They sat at opposite ends of the room, surrounded by members of Don Winston’s household. Crossbeams of sweat rapidly appeared on everyone’s backs. Their opening statements were stage-whispered through cupped hands, as if they were loudly passing on secret information.

“Eduardo we would like a bit more time for the cattle.”

“I want them today.”

“We lost many in flooding and the cold chills last year, and we can give you calves right now.”

“Not the pregnant cows?”

“We would like to amend the contract again,” said Don Winston’s son, Pito.

Luttwak made an elaborate grimace of disappointment and stood up and left the room, apparently to take a self-guided tour of the house. Together we walked to the veranda through Don Winston’s bedroom. Luttwak took a picture off the wall. It was an old photo of Don Winston riding a horse, and below it were a series of exclamations: Courage! Honour! Perseverance!

“Don Winston, this is a wonderful picture of you riding!”

“Thank you, Eduardo!”

“Don Winston, I will be forced to steal your wife if you don’t return my cattle by tomorrow!”, Luttwak said with theatrical menace.

“We will try, Eduardo,” said Don Winston, with theatrical penitence.

It was hard to tell how much of this performance was for my benefit, why Luttwak badly needed the cows now, and what the effect of walking around Don Winston’s house had been. But something had registered. It was agreed that the cattle would be returned in a week. We moved back to the veranda in less tense spirits.

We had reached the denouement. Luttwak mock-threatened to steal Don Winston’s wife once more. We exited the room. Outside the house, Luttwak pointed out a Mitsubishi Triton pick-up truck parked outside, which he cited as evidence of the company’s fresh gains in Bolivia. A brief discussion about the merits of the Triton followed. Everyone started petting the truck. Luttwak said he would inform the board of Toyota about this unexpected threat to their business in South America.

“I don’t particularly like serving states,” Luttwak told me over dinner in the main square of Trinidad two days later. “I prefer peoples and clans to states. But after 9/11, I wanted to do something again for America.” That opportunity did not arise. Instead, Luttwak continued, “I got a call from Nicolo Pollari” – the former head of Italy’s military intelligence agency. “He said, ‘Edward, I know what we’re doing – but I want you to do what we’re not doing.” According to Luttwak, the Swiss government had helped fund an Italian security operation to keep al-Qaida operatives from entering western Europe. And the Italians wanted Luttwak’s help.

Luttwak told me that he began by identifying the main entry points for al-Qaida members coming to Europe. In each of these locations, he put into action a carefully tailored plan. To deal with the operatives coming into Sicily by boat, Luttwak conducted town-hall-style meetings in cinemas near the harbours. Accompanied by his closest friend from childhood, the politician Calogero Mannino, Luttwak arranged a series of meetings with boat skippers, in which he explained they would not get into any kind of trouble – neither with the mafia nor the government – for following his instructions. “I told the ship captains that they would have to turn everyone in [who seemed suspicious]. I said, ‘You’ll know who they are because they will be young men, they won’t have trouble paying, and they’ll be less flea-bitten than the others.’” As part of his work for the Italians, Luttwak also claims to have conducted operations in Trieste and the Austrian city of Klagenfurt. In the Italian port city of Bari, Luttwak says his work included helping the police fight off the local mafia, who were helping Albanian smugglers deliver rafts that included al-Qaida operatives onto the country’s shores.

Luttwak enlisted another old friend, a scholar of Arabic at the Catholic University in Milan, to conduct the interrogations of the captured suspects. “She could tell the accents of the men, search out the obvious lies, and determine their true origins,” he said. “No one was tortured,” Luttwak reassured me several times. “Instead we gave them speeches: ‘We’re going to take you out of solitary and put you in the main prison. You know Italian prisoners were very moved by September 11. Some of them cried while watching the towers go down. So they’re going to rape you several times before they kill you.’” Luttwak claims his intelligence operation was spectacularly successful. “The Italians are frivolous about many things,” he told me, “but not about counter-terrorism.”

A couple of days later, we began the long return journey. The flight back to Santa Cruz was rocky. “The problem is that the pilots don’t use radios with each other so you never quite know when you’re going to get crashed into by another plane,” said Luttwak, with his impish smile. On the flight he carefully paged through two back issues of the Times Literary Supplement, which he carries with him everywhere (he finds the London Review of Books is “too bulky”). “Why is Warnie Lewis ‘the much maligned brother of CS Lewis?’” he asked me in the middle of some turbulence. “Why ‘much-maligned’?”

From Santa Cruz, Luttwak was flying to Zurich, where he has a regular job advising the local police and a firm he did not want to make public. In the passport line, I found him standing with a Swiss man employed in the fast-food business. “This man works in an industry that has yet to have its Nuremberg trials,” Luttwak declared. The Swiss man smiled weakly. “He’s a chicken nugget consultant! If there’s one point on which I agree with the leftist weaklings, it’s 1) that McDonald’s must go and 2) that American citizens should be forced en masse to take a course in phenomenology, so that they can develop the proper philosophical disposition necessary for understanding the incarnate evil of the chicken nugget.” The Swiss man was flustered, trying to calculate to what degree he had just been insulted.

This man works in an industry that has yet to have its Nuremberg trials. He’s a chicken nugget consultant!

Edward Luttwak

“Most people live such pointless lives,” said Luttwak as we walked toward his gate. “Not desperate lives – they have cable television – but pointless. For politicians, it’s not pointless, but it always ends in disappointment and bitterness. But meaningful? Their lives are not as meaningful as the Mennonites. The Mennonites are free in the Hegelian sense – they are self-consciously free. And they have unintentionally revealed the ongoing fraud of American agriculture. They don’t destroy the land, they don’t drug animals to death – they make vast profits using 18th-century technology. Personally, I cannot live that life, but I want it to flourish. I relate with Ulysses because I demand an interesting life. I demand it.” And with that, Luttwak boarded his flight.

In April, two months after his trips to Bolivia and Switzerland and a stopover in Asia to help design a new intelligence agency for an Asian country that he insisted I refer to only as “the Asian country” whenever we were in public, Luttwak drove to New York to help prepare for his wife’s art opening at a gallery in Chelsea. Don Winston still owed him eight mules, and Luttwak was in negotiations with a Mennonite colony in the Beni to sell a large chunk of his land. I met him at a small television studio on West 30th Street, where he was appearing on the popular Italian political talk show Servizio Pubblico. Luttwak sat in a black room at a small table in a dark grey suit, as a young woman applied makeup and a technician wired him up.

The segment was devoted to the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean. Four days earlier, another migrant boat had sunk off the coast of Libya, killing roughly 800 asylum seekers. The commentators on the show spoke about how it was a terrible tragedy and how Italy needed to do more. Luttwak’s eyebrows raised in a mute appeal for mercy from this do-gooding nonsense. “This is what makes Italian leftists so vulnerable,” he said to the room in New York between live segments. “English or French leftists would come on with coherent arguments and rebuttals prepared. But in Italy everyone just wants to be considered buonista – morally pure – so they’re just easy to quash. I’ve said before that the Italians must destroy the boats before people board them on the Libya coast. You attach limpet mines to the hulls. The Renzi government is taking up my idea.”

Afterwards, as we walked to Dalya’s opening, I asked Luttwak once more why he was interested in strategy. “You seemed bored in there,” I said. “Isn’t it tiring to spend your day turning conventions on their head?”

“No,” said Luttwak, “strategy is about looking for turning points. Politics is too predictable. Look at Hillary. She is an empty carapace with ambition rattling inside. You can predict everything she does. Strategy is about being unpredictable.”

“But doesn’t that unpredictability become predictable?” I asked. “What happens when every army in the world abides by strategic logic?”

“But they never will,” said Luttwak, “because most people cannot master their emotions. Above all, strategy is about mastering your emotions.” And the emotions of others, he might have added. For all of this commitment to the concrete, Luttwak sells something extremely abstract: a form of self-realisation that gives his clients the fleeting sense that they, and the agencies under their command, have achieved mastery not only of their emotions, but of the vicissitudes of their historical moment. Like psychoanalysts who identify meaningful patterns in their patients’ idle chatter, Luttwak sees glaring chances for strategic mastery in the dullest bureaucratic reports and inventories.

In my time with Luttwak, it became clear that he didn’t simply embody his own ideas, he overfilled them; his provocations and factual barrages were the spider’s web he wrapped around his helpless listeners. But even his exaggerations – the “categorical assertions” that ruffle the likes of Brzezinski and Wolfowitz – contained something beyond strategic value: they advanced the sense that Luttwak was more daring than they were; that others have traded excitement for power, that they have traded the machete for the desk, whereas Luttwak has kept hold of both in a world that would not seem to tolerate such people, much less make them rich.

We were nearly at the gallery. Luttwak stopped to tie the laces of his black sneakers on a fire hydrant. “If I were starting out again now I would be a biologist,” he said. “I would be a student of bacteria. Every second there is an Iliad unfolding in our intestines. The variables are infinite compared to strategy or politics.”

When we reached the gallery, Dalya and Luttwak embraced. The room filled with more than 60 people. Family and friends and some art dealers arrived. Luttwak walked in circles around the room, providing a running commentary on the assembled guests. “This man’s father was a graduate of the gulag and taught me everything about forgery,” said Luttwak of one. “But he never came to anything.”

Stories and lore flowed electrically around Luttwak, but for the moment he was resisting the current. He was on good behaviour. Tonight was about his wife. An old Israeli friend sidled up to him. “How are you holding up, Edward?”

“I’ll be fine until peace breaks out.”

• Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, or sign up to the long read weekly email here.

This article was amended on 9 December. An earlier version of the piece referred to a certificate congratulating Edward Luttwak for his contribution to the design of the Israeli M-47 tank. The tank in question was, in fact, the Merkava.

This article was amended on 14 December 2015. It originally included a quote about moving to Milan from a 2001 interview with Luttwak, and stated that the quote had come from the writer’s interviews with Luttwak. The quote was actually from an interview with Corey Robin, and was mistakenly used instead of one from the writer’s own interviews with Luttwak about his childhood. The attribution has been corrected.

No comments:

Post a Comment