Summary: Here Stratfor looks at a seldom-mentioned aspect of the Paris attacks. Their roots lie deep in France’s history, allowing large-scale immigration from its colonies to provide cheap labor for its corporations. Just as American has done. But as Frances’s Jews discovered, France has little ability to assimilate foreigners. Its slow economic growth makes this even more difficult. Paris was a result.

The governor of the colony, William Bradford, abolished this system and gave each household a parcel of land. With private property to call their own, the Pilgrims were suddenly very industrious and found themselves with more corn than they knew what to do with. So they invited the Indians over to celebrate. (In some other versions, the first Thanksgiving is not a feast but a brief respite from famine. But the moral is always the same: socialism doesn’t work.) The same commune-to-capitalism, famine-to-feast story is told of Jamestown, the first English settlement, in 1607.

It’s a sad story, showing how we have come to believe stories that are almost an inversion of the truth — told to us for tawdry political actors. Annual debunkings by journalists and historians have had little effect.

Some attempt direct attacks on the liars, such as

this by Ben Norton at Salon: “Rush Limbaugh’s ‘

The True Story of Thanksgiving‘ is a lie-filled load of stuffing that turns villains into victims” — “Tea Party Thanksgiving mythology bludgeons socialism with lies while covering up capitalists’ genocide of Natives.”

Some do rebuttal with detailed narratives, like the Charles C. Mann’s superbly told account tin the Smithsonian Magazine; “

Native Intelligence” (December 2005). Some articles attempt to shock us into awareness, telling the facts in an entertaining way from another perspective. The best of these I’ve seen is Scott Alexander’s brilliant “

The Story Of Thanksgiving Is A Science-Fiction Story” (2013).

Domestic Concerns

From France’s perspective, the most immediate concern the Paris attacks raise is that French citizens were killed. Any government that fails to protect its citizenry risks being replaced, meaning that officials must work quickly to neutralize the attackers before doing the same for any accomplices who were directly involved. Then the government must try to prevent similar attacks from taking place in the future. The first two of these actions are already well underway, and progress toward the third is evident. Hollande has asked to extend emergency powers for three months, to deploy an extra 5,000 police officers over the course of two years, and to amend the constitution to broaden surveillance powers. By all appearances, France seems to be on the verge of becoming a closely watched state in the coming years — much like the United Kingdom, which has one surveillance camera in place for every 11 Britons.

The Nov. 13 attacks also play into domestic politics, and the government will want to be seen avenging its citizens and punishing the offending party for its actions. This appears to be a large part of the motivation behind Paris’ increased bombings of Islamic State targets overseas. Hollande is the leader of the center-left Socialist Party, which traditionally takes a softer line on social, security and privacy issues and is therefore vulnerable to recriminations from the public that it has not done enough to protect French citizens. Adding to this problem, France has experienced other terrorist attacks this year, most notably in January when gunmen attacked the offices of the Charlie Hebdo newspaper, and people expected the government to have learned from these experiences in addressing security threats.

Regional elections in December will give voters across the country a chance to show their displeasure with the government’s response, making the situation even more urgent for Hollande. The anti-immigration National Front has enjoyed a surge in support in recent years, with party leader Marine Le Pen polling strongly ahead of the 2017 presidential election. For the more moderate voter, there is also the center-right Republicans party headed by former President Nicolas Sarkozy. The former president has long divided public opinion with his tough stance on immigrants and security, which dates back at least to his time as France’s interior minister in the early to mid-2000s.

Implications for France’s European Ties

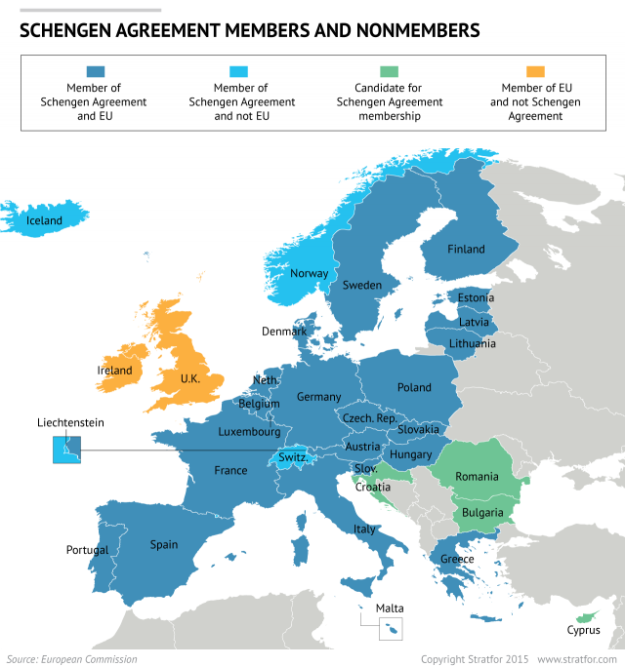

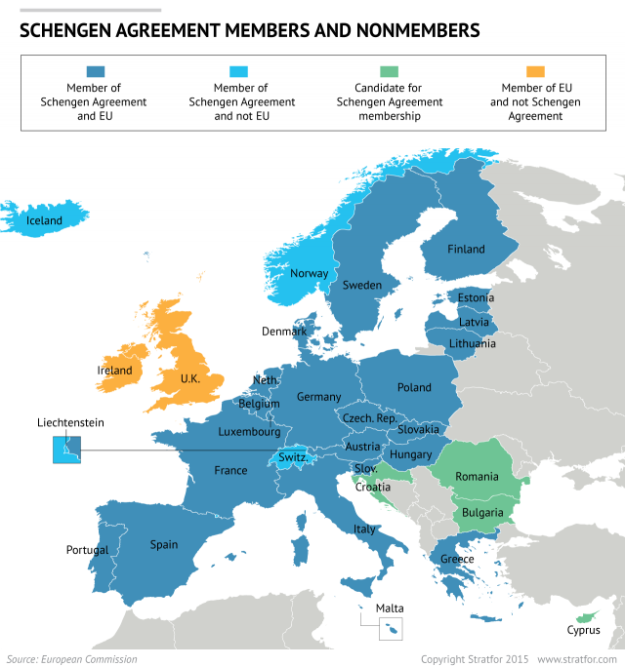

The Paris attacks have also exacerbated problems that have been brewing in France’s relationship with the rest of Europe. A passport found at the scene of the crime appears to be linked to an immigrant who passed through Greece and up through the Balkans to get to France within the past two months. Doubts have since been raised about the authenticity of the passport, but the damage has been done, and many in France are linking the attacks to immigrant flows. As a result, the Schengen Agreement, which allows free travel across borders within member states, is under serious threat.

The immigrant link may or may not prove valid, but an even more damning piece of evidence has arisen against Schengen: the Belgian connection. Belgium has emerged as a key staging point of the attacks, and the perpetrators seem to have done a great deal of their planning in Brussels. Belgium’s connectivity, small size and membership in the Schengen area mean that it is extremely easy to enter several countries from Belgium within a short time. Consequently, many see the Schengen Agreement as a facilitator in the attacks.

The events of Nov. 13 have also altered France’s budgetary situation. In November 2014, France fell afoul of the European Commission for its fiscal laxity, and its 2015 budget wasn’t approved until several months into the year. This time around, the commission has been considerably less strict with its charges for the most part, mainly because of improvements in the overall economic climate, but it is still tasked with maintaining the union’s economic guidelines. Hollande’s Nov. 16 announcement that security concerns trump austerity, and that budgetary requirements will take a back seat since France is at war, cannot have been received well in Brussels, whether true or not.

Aside from the immediate considerations of the commission’s mood, France may still be able to borrow at extremely cheap rates largely because of the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing program, but this will not help its fiscal position. Borrowing to finance France’s heightened spending will layer onto the country’s already high debt levels. As a result, France will become even more firmly enmeshed in the Mediterranean group of eurozone countries with heavy debt burdens, relying on the European Central Bank and the prevailing economic climate to keep interest repayments low. At best, this will increase the chances of friction with Germany, and at worst, it will precipitate a debt crisis.

Older Problems

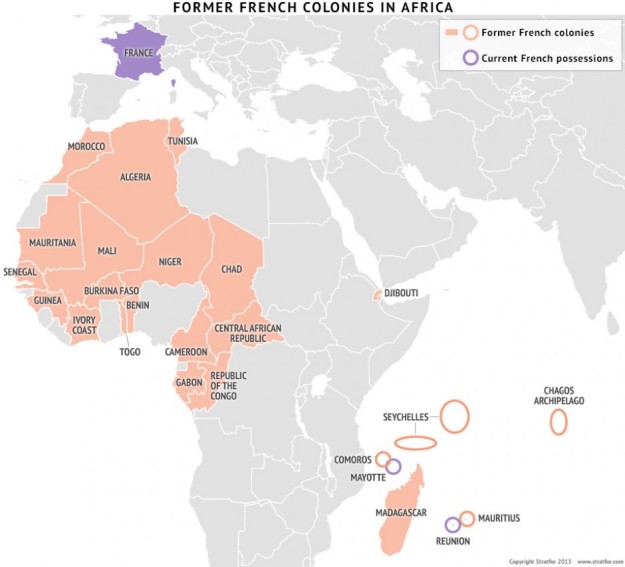

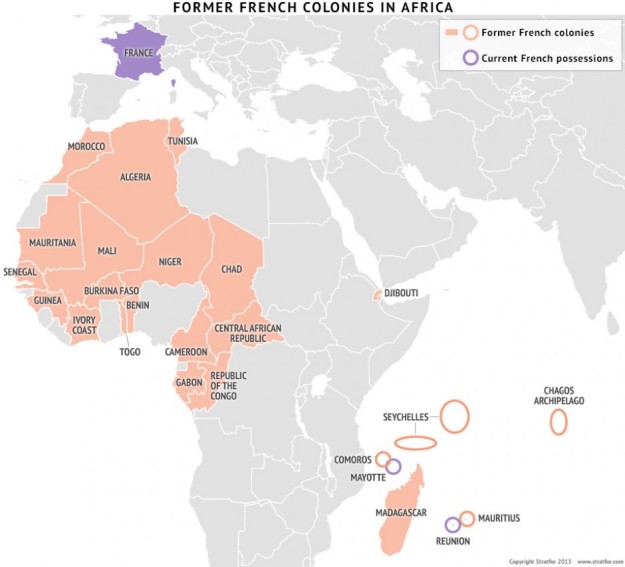

But France’s biggest concerns in the wake of the Paris attacks speak to some of the country’s much more deeply-rooted issues. Half of the attackers were Frenchmen. French law prohibits the inclusion of religious affiliation on national censuses, but estimates suggest that around 7.5 percent of France’s population is Muslim, with a great portion of that group of North African extraction. Most of the recent terrorist incidents in France have stemmed from this part of the population, which tends to be poorer and more isolated than other groups.

The roots of this reality trace back to France’s experiences in colonizing Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and then to the messy independence processes these colonies underwent, particularly Algeria’s War of Independence from 1954 to 1962. Bombings, killings and police brutality on both sides of the Mediterranean created enmity between the two populations, which only continued as growing numbers of Algerians emigrated to France. After World War II, France experienced a significant growth spurt in its “Trente Glorieuses” (“Thirty Glorious Years”) and it needed cheap labor — a need North African emigres helped fill.

The newcomers made homes for themselves around France’s industrial centers, including Paris, Lyon and Marseilles, but their high numbers and low wealth, combined with existing antipathies, inhibited their ability to integrate. The country became dotted with pockets of poor, disaffected and mainly Muslim communities that struggled to find gainful employment and break the cycle of poverty in which they found themselves. It is from these communities that the Islamic State appears to have had some success in recruiting, and it is their problems that France must solve if it hopes to prevent the homegrown threats the Paris attacks brought to light.

“In France, New Attacks Come From Old Problems”

is republished with permission of Stratfor.

————————————————-

About the author

Mark Fleming-Williams follows political economies, trade and financial trends around the world for Stratfor. He joined the company with more than a decade of experience working with the investment banking sector in London. Mr. Fleming-Williams holds a master’s degree in international business from Leeds University Business School and an investment management certificate from the CFA Society of the U.K. He has studied and worked in both Madrid and Australia. He speaks French at an advanced level and has an intermediate command of Spanish.

About Stratfor

the attacks, and the perpetrators seem to have done a great deal of their planning in Brussels. Belgium’s connectivity, small size and membership in the Schengen area mean that it is extremely easy to enter several countries from Belgium within a short time. Consequently, many see the Schengen Agreement as a facilitator in the attacks.

No comments:

Post a Comment