AUG 7, 2015

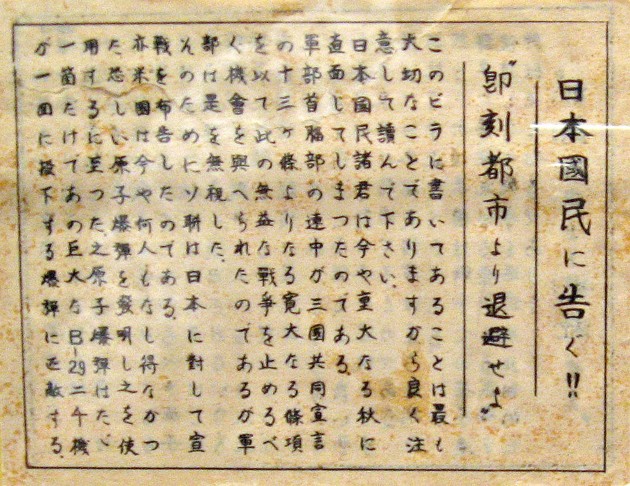

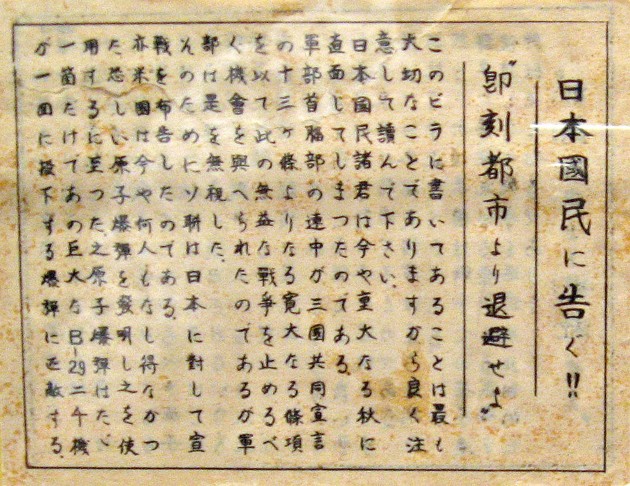

Seventy years ago, on the morning of August 6, 1945, a B-29 Superfortress named Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. A short time later, other B-29s began dropping leaflets on Tokyo. “Because your military leaders have rejected the 13-part surrender declaration,” the leaflets said, “we have employed our atomic bomb. ... Before we use this bomb again and again to destroy every resource of the military by which they are prolonging this useless war, petition the emperor now to end the war.”

There was no way that Japanese civilians could petition Emperor Hirohito to accept the terms of the July 26 Potsdam Declaration outlining the Allies’ surrender demands—among them the complete disarmament of Japanese forces and the elimination “for all time the authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest.” But the leaflets reflected reality: Only the emperor could end the war. To do that, though, he would have to defy his military leaders, knowing that his call for peace would almost certainly inspire a military coup.

When news of the Nagasaki bombing came on August 9, the Supreme War Direction Council reacted not by moving toward peace but by declaring martial law throughout Japan. With the cabinet unable to reach a consensus on whether to accept the surrender terms, and War Minister Korechika Anami leading the opposition, its members finally turned to the emperor for a decision.

Shortly before midnight, Hirohito, a weary, sad-eyed man, walked into the hot, humid air-raid shelter 60 feet below the Imperial Library where his 11-member cabinet was gathered. He sat in a straight-backed chair and wore a field marshal’s uniform, ill-fitting because tailors were not allowed to touch this man revered as a god. The gathering itself was an extraordinary event known as a gozen kaigin—“a meeting in the imperial presence.” Hirohito had been emperor since 1926 and, as commander in chief of the Japanese armed forces, had often been photographed in his uniform astride his white horse during the war. But U.S. propaganda portrayed him as a figurehead and blamed the generals for prolonging the war.

Hirohito patiently listened as each cabinet member presented his argument. At 2 a.m. on Friday, August 10, Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki did something that no prime minister had ever done: He asked Hirohito for an imperial command—known as the Voice of the Crane since the sacred bird could be heard even when it flew unseen.

Speaking softly, Hirohito said he did not believe that his nation could continue to fight a war. There is no transcript of his address, but historians have pieced together accounts of his rambling words. He concluded: “The time has come when we must bear the unbearable. ... I swallow my own tears and give my sanction to the proposal to accept the Allied proclamation.”

On August 10, the Japanese Foreign Ministry transmitted a response to the Allies, offering to accept the terms of the Potsdam declaration with the understandingthat those terms did not “comprise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a Sovereign Ruler.” By August 11, Japan had received the Allied reply, including the U.S. insistence that “the authority of the Emperor and the Japanese Government to rule the state shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied powers who will take such steps as he deems proper to effectuate the surrender terms.”

In America, most people believed that peace had come. “Japan Offers to Surrender,” bannered The New York Times; another Times story was headlined “GI’s in Pacific Go Wild With Joy ‘Let ‘Em Keep Emperor’ They Say.” In Japan, however, the war went on. The Japanese offer of surrender, and the Allied reply, were known only to high government officials. Morning newspapers in Japan on August 11 carried a statement in the name of General Anami and addressed to the army: “The only thing for us to do is fight doggedly to the end ... though it may mean chewing grass, eating dirt, and sleeping in the field.”“I desire the cabinet to prepare as soon as possible an imperial rescript announcing the termination of the war.”

But on the morning of August 14, another blizzard of leaflets swirled over Tokyo and other cities, and this time they contained news of the messages exchanged between Japan and the Allies. Marquis Koichi Kido, Hirohito’s closest advisor, later recorded in his diary that seeing one “caused me to be stricken with consternation” over the possibility that some leaflets could “fall into the hands of the troops and enrage them,” making a military coup d’état “inevitable.”

A coup, in fact, was already underway. If Anami were to give his support to the plot, much of the Japanese Army—a million soldiers in the Home Islands—would almost certainly rise against the cabinet with the claim that the emperor had been duped by cowardly civilians. If Anami resigned from the cabinet, it would fall and Japan would fight on.

At Kido’s frantic urging, the emperor declared another gozen kaigin in the air-raid shelter, where he issued an imperial command: “I desire the cabinet to prepare as soon as possible an imperial rescript announcing the termination of the war.” Hirohito knew that publication of the rescript—a proclamation of the gravest import—would not be enough. He decided to be a true Voice of the Crane. He would step before a microphone and read the rescript to his people, who had never before heard him speak.

That night, the emperor’s offer to surrender reached Allied governments, and the designated Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, Army General Douglas MacArthur, began the formalities. About the same time, Anami’s brother-in-law, Lieutenant Colonel Masahiko Takeshita, was urging Anami to lead a coup. Anami refused.

Kido and other aides to the emperor started hurriedly arranging for the imperial broadcast with stunned directors of the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK). The chairman of NHK brought a recording team to the palace complex to capture Hirohito’s words. That afternoon, Kido recorded in his diary, a visitor noticed that far more soldiers than usual were on the palace grounds. “I am afraid of what may be happening at the Imperial Guards Division,” he said, referring to the elite soldiers who guarded the emperor and the palace.

The NHK staff waited while cabinet members haggled over the wording of the rescript. At about 8 p.m., copyists were finally given a scrawled, heavily edited manuscript. But as they began transcribing it into classic calligraphy, they were given more changes. To their aesthetic horror, the copyists had to make corrections on tiny pieces of paper and paste them in. A leaflet dropped from a B-29 plane after the bombing of Hiroshima, announcing American plans to drop another bomb (Wikimedia)

A leaflet dropped from a B-29 plane after the bombing of Hiroshima, announcing American plans to drop another bomb (Wikimedia)

A leaflet dropped from a B-29 plane after the bombing of Hiroshima, announcing American plans to drop another bomb (Wikimedia)

A leaflet dropped from a B-29 plane after the bombing of Hiroshima, announcing American plans to drop another bomb (Wikimedia)

During the regular 9 p.m. Japanese radio news, listeners were told that an important broadcast would be made at noon the next day. Mimeographed copies of the final text went to newspapers, with a publication embargo until after the emperor’s broadcast.

At 11 p.m., Hirohito was driven the short distance across the palace grounds from his living quarters to the blacked-out building of the Household Ministry, which ran the affairs of the imperial family. In the audience hall on the second floor, the NHK technicians bowed to the emperor. Hirohito, looking perplexed, stepped before the microphone and asked, “How loudly should I speak?” Hesitatingly, an engineer respectfully suggested that he speak in his normal voice. He began:

To our good and loyal subjects: After pondering deeply the general trends of the world and the actual conditions obtaining in our empire today, we have decided to effect a settlement of the present situation. ... Let the entire nation continue as one family from generation to generation, ever firm in its faith in the imperishability of its sacred land.

When he finished, he asked, “Was it all right?”

The chief engineer stammered: “There were no technical errors, but a few words were not entirely clear.”

The emperor read the rescript again, tears in his eyes—and soon in the eyes of others in the room.

Each reading was only four and a half minutes long, but the speech spanned two records. The technicians picked the first set of records for the broadcast, but they kept all four, putting them in metal cases and then into khaki bags. The technicians, like everyone else in the palace, had heard rumors of a coup. They decided to stay there that night rather than attempt a return to the NHK broadcasting studio, out of fear that army mutineers would attempt to steal and destroy the recordings. A chamberlain placed the records in a safe in a small office used by a member of the empress’s retinue, a room normally off-limits to men. Then he hid the safe with a pile of papers.

In the early hours of August 15, Major Kenji Hatanaka, a fiery-eyed zealot, and Army Air Force Captain Shigetaro Uehara burst into the office of Lieutenant General Takeshi Mori, commander of the Imperial Guards Division. Hatanaka fatally shot and slashed Mori, and Uehara beheaded another officer. Hatanaka affixed Mori’s private seal to a false order directing the Imperial Guards to occupy the palace and its grounds, sever communications with the palace except through Division Headquarters, occupy NHK, and prohibit all broadcasts.

Meanwhile, Major Hidemasa Koga, a staff officer with the Imperial Guards, was trying to recruit other officers into the plot. At the palace, soldiers supporting the coup, with bayonets affixed to their rifles, rounded up the radio technicians and imprisoned them in a barracks. Wearing white bands across their chests to distinguish themselves from guards loyal to the emperor, they stormed the palace and began cutting telephone wires.“The war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage. Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb.”

Koga, hoping to find and destroy what he thought was the single record of the emperor’s message, ordered a radio technician to find it. The technician, unfamiliar with the palace, led several soldiers into the labyrinth. Soldiers roamed palace buildings, kicking in doors, flinging contents of chests onto the polished floors. The emperor remained in his quarters and watched through a slit in the steel shutters protecting his windows.

Lieutenant Colonel Takeshita, meanwhile, tried again to bring Anami into the plot. Anami once more declined. Instead, with Takeshita in the room, Anami knelt on a mat, drove a dagger into his stomach, and drew it across his waist. Bleeding profusely, he then removed the knife and thrust it into his neck; Takeshita pushed the knife deeper until Anami finally died.

Rebellious soldiers swarmed into the NHK building, locked employees in a studio, and demanded assistance so they could go on the air and urge the nation to fight on. Shortly before 5 a.m. on August 15, Hatanaka walked into Studio 2, put a pistol to the head of Morio Tateno, an announcer, and said he was taking over the 5 o’clock news show.

Tateno refused to let him near the microphone. Hatanaka, who had just killed an army general, cocked his pistol but, impressed by Tateno’s courage, lowered the gun. An engineer, meanwhile, had disconnected the building from the broadcasting tower. If Hatanaka had spoken into the microphone, his words would have gone nowhere.

It took most of the night for troops loyal to the emperor to round up the rebels. At dawn, they finally removed the mutineers from the palace grounds. Now judging it safe to leave, the NHK engineers brought the emperor’s records to the radio station in separate cars using different routes. They hid one set in an underground studio, and prepared to play the other. At 7:21 a.m. Tateno went on the air and, without recounting the adventures of the night before, announced, “His Majesty the emperor has issued a rescript. It will be broadcast at noon today. Let us all respectfully listen to the voice of the emperor. ... Power will be specially transmitted to those districts where it is not usually available during daylight hours. Receivers should be prepared and ready at all railroad stations, postal departments, and offices both government and private.”

At noon, throughout Japan, as the emperor’s voice was heard, people sobbed. “It was a sudden mass hysteria on a national scale,” Kazuo Kawai, editor of Nippon Times, later wrote. The emperor spoke in classical language not readily understandable to most Japanese people. The “war situation,” he said, “has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage, while the general trends of the world have turned against her interest. Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb. ... We have resolved to pave the way for a grand peace for all the generations to come by enduring the unendurable and suffering what is insufferable.” He never used the words “defeat” or “surrender.”

After the broadcast, Hatanaka ended his mutiny standing outside the palace gates, trying to hand out leaflets that called on civilians to “join with us to fight for the preservation of our country and the elimination of the traitors around the emperor.” No one took the leaflets. Hatanaka shot himself in the head.

In the days that followed the emperor’s radio address, at least eight generals killed themselves. On one afternoon, Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki, commander of the Fifth Air Fleet on the island of Kyushu, drank a farewell cup of sake with his staff and drove to an airfield where 11 D4Y Suisei dive-bombers were lined up, engines roaring. Before him stood 22 young men, each wearing a white headband emblazoned with a red rising sun.

Ugaki climbed onto a platform and, gazing down on them, asked, “Will all of you go with me?”

“Yes, sir!” they all shouted, raising their right hands in the air.

“Many thanks to all of you,” he said. He climbed down from the stand, got into his plane, and took off. The other planes followed him into the sky.

Aloft, he sent back a message: “I am going to proceed to Okinawa, where our men lost their lives like cherry blossoms, and ram into the arrogant American ships, displaying the real spirit of a Japanese warrior.”

Ugaki’s kamikazes flew off toward the expected location of the American fleet. They were never heard from again.

The end finally came on September 2. The emperor was secure in his palace. His voice—the voice of the crane—had been heard throughout the land. Nearby, on the deck of the U.S. battleship Missouri, moored in Tokyo Bay, Japan surrendered to the Allies while a thousand U.S. carrier planes and B-29 bombers flew over. General MacArthur, after presiding over the surrender ceremony, was now the de facto emperor of Japan.

No comments:

Post a Comment