2 August 1990

I was not yet twenty one, had big metal-band-era hair and acid washed jeans, along with a night job that left a little time for watching cable television, when I met a guy named Wolf Blitzer narrating the opening of what would become the First Gulf War. I have many friends and colleagues who were part of Operation Desert Storm as military personnel; their reflections and recollections are fascinating and much different than mine. In this post remembering the 25th anniversary of Operation Desert Storm, I wanted to reflect on my personal impressions as a college student and civilian, to ask questions about the legacy of this conflict in terms of how civilians now view war, and the implications for the military-civilian culture gap. As a military ethicist now reflecting on those experiences, it is clear to me that this short conflict had profound impact on expectations of current and future conflicts, often in problematic ways that need to be directly addressed moving forward.

It looked exactly as I imagined that modern war in the computer age ought to look, narrated by a young, cool guy named Wolf.

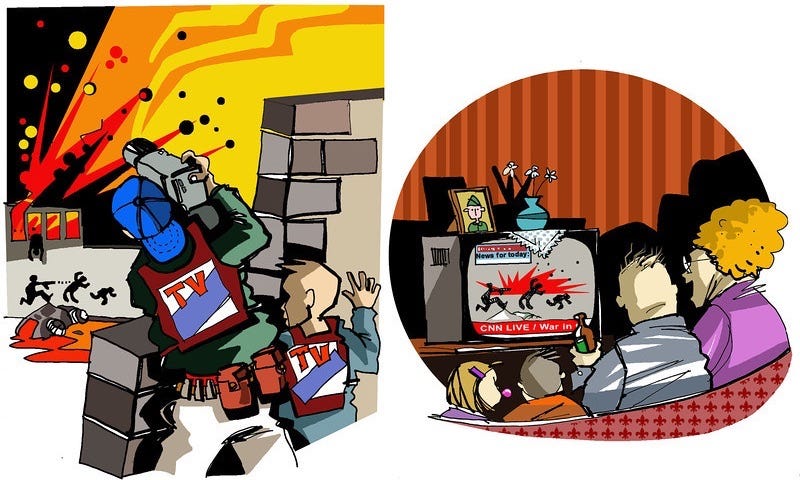

As a college student majoring in philosophy and international relations (but no clear sense about the intersection of these areas), I was drawn to what was effectively the first CNN conflict. The run up to the war included breathless commentary and comparisons to Hitler and World War II, featured what seemed to be a broad “coalition of the willing” engaged in a response to a clear cut case of aggression. Once the conflict began, there were impressive visuals of the air war and ‘sorties,’ which growing up as the child of an Air Force NCO provided a chance to bond with my father and reflected the aesthetic of my generation who cut their teeth on Star Wars movies and space invader video games. It looked exactly as I imagined that modern war in the computer age ought to look, narrated by a young, cool guy named Wolf.

In a way, it was an epic, movie-like presentation of American military and political triumphalism that was moment by successful moment erasing the imagery of the Vietnam War and its perceived failures.

“The Luckiest Man in Iraq” — General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, Jr.

In preparation for the ground conflict, there was a parade of former generals and other military boosters showing off the latest military technologies and extolling the professional acumen, character and superiority of American military technology and personnel. These presentations were firmly optimistic and positive, with clear characterizations of possible damage to the enemy (who was presumed to be weak and not capable of much resistance), with little discussion of messy things like collateral damage and non-combatant harms; these weapons were capable of precision and would be used in surgical strikes resulting in a swift victory. There was very little critical questioning from the press (continued in the highly choreographed daily military briefings from General Norman Schwarzkopf among others), even as I was vaguely aware of arguments that this was about oil and not about Kuwait’s sovereignty.

Coalition Troops Killed by Country in Operation Desert Storm (Wikimedia Commons)

In a way, it was an epic, movie-like presentation of American military and political triumphalism that was moment by successful moment erasing the imagery of the Vietnam War and its perceived failures. There were 200,000 Iraqi casualties, but little of these were seen on CNN while the couple hundred US casualties were trumpeted as some kind of contemporary Agincourt. From my perspective in front of a TV screen in Fargo, North Dakota it was all beautiful, clean and precise and over before I had time to become bored or to question the narrative and imagery presented. And we won. The victory was decisive and impressive, credited to the superior technology and moral superiority of the US military forces. Vietnam had been banished and American exceptionalism vindicated on TV with great visuals, a superb narrator and compelling cast of characters.

…these reflections demonstrate a certain civilian experience of war that, in my view, was not entirely uncommon and still profoundly shapes how civilians in the US experience and think about contemporary conflicts…

Of course, these are but my own hazy personal reflections from twenty-five years ago. This is not to say that this what the experience of war was like from either the coalition or Iraqi military sides; it is to say that these reflections demonstrate a certain civilian experience of war that, in my view, was not entirely uncommon and still profoundly shapes how civilians in the US experience and think about contemporary conflicts like Iraq, Afghanistan and the emerging conflict against ISIS.

1991 Topps Desert Storm Trading Card featuring President George H.W. Bush (The Cardboard Connection)

Saddam-Hitler postcard distributed in Great Britain and the United States by the Free Kuwait Campaign. The backside of the postcard stated: “On the morning of 2 August 1990, the independent, sovereign state of Kuwait was subjected to an unprovoked invasion by Iraqi forces. Following the invasion, Iraqi troops committed brutal atrocities against the population. This attack, contrary to all fundamental principal of International law, and in total breech of the Charter of United Nations, has been condemned by all the civilized nations of the world as a naked act of aggression. Your voice and vote can make a difference. STOP Iraqi aggression and prevent further atrocities. Please write to your government representative for action. Oppose Iraqi aggression now.” (Muna al-Mousa & Michael Lorrigan via Psywarrior.com)

The first thing to note was the stark moral clarity (or so it seemed) reflected in the moral consensus as evidenced by the “coalition of the willing” and President George H.W. Bush’s explicit invocation of the jus ad bellum criteria of the Just War Tradition in his speech asking to go to war.[1] There was a clear narrative of Last Resort, supported by diplomatic efforts, UN resolutions and public conversations about how to deal with Saddam Hussein’s actions. There was also Just Cause in the violation of Kuwaiti sovereignty and the threat to the international community and peace complete with the Saddam is Hitler imagery invoking World War II. The fact that Kuwait was a much smaller country and that Saddam had engaged in a long war with Iran only seemed to fit the narrative and make clear that collective military force was necessary to stop him and redress the injustices committed.

A Brigade of the U.S. 3rd Armored Division masses in northern Saudi Arabia in preparation for the invasion of Iraq during the Gulf War, February 1991. (Wikimedia Commons)

Second, this conflict seemed to fit nicely into the conventional war paradigm of air power and ground troops and vehicles that seemed in many ways a throwback to World War II only with newer, shinier technology. Unlike World War II, this one was very short and from the US perspective, relatively bloodless. There were precision, surgical strikes and sorties flown with images of destruction of physical things, but very few pictures of the human toll, of blood, pain and suffering that inevitably goes with war and its effects. It was clean, scientific and technological in an era when Americans (as they still do) think of technology as a way to make life easier, to clear up messiness and as an engine for progress.

…controlling the narrative and keeping the conflict short and decisive was the perfect recipe for a successful war.

This fit perfectly with the birth of the 24/7 news cycle mentality and the shrinking of the national attention span with greater and greater cultural emphasis on immediacy and convenience. War had now become yet another good to consume and be tweaked according to our expectations and preferences. This perception was enhanced by the degree to which the military controlled the narrative (in reaction to the view by some that the press lost the war in Vietnam and undermined the support on the home front); controlling the narrative and keeping the conflict short and decisive was the perfect recipe for a successful war.

Third, this conflict was experienced by many civilians (and perhaps the military as well) as the antidote for and repudiation of the Vietnam syndrome. Vietnam had been a long, indecisive conflict fought with unconventional/asymmetric tactics against an elusive and changing enemy; the cause was eventually viewed as morally murky and from the civilian perspective ended with a retreat and defeat of sorts. The Gulf War was a decisive victory, fought with conventional tactics with no question as to who the enemy was and where to find him. From the civilian point of view, this redeemed the Vietnam experience; there was no question about the competency and moral character of the US troops and we won battles which settled the war.

Implications

Given these points, what are we to conclude about the implications of Operation Desert Storm for contemporary and future conflicts?

Failure is simply not an option.

U.S. soldiers on a search-and-destroy patrol in Phuoc Tuy province, South Vietnam, June 1966 (U.S. Army Photo)

U.S. soldiers on a search-and-destroy patrol in Phuoc Tuy province, South Vietnam, June 1966 (U.S. Army Photo)

Failure is simply not an option. Patton famously observed that Americans will not tolerate a loser, and this is especially true with respect to military matters and war.[2] We see this risk aversion in the increased use of unmanned systems (including drones and robots), a concerted focus on force protection and resistance on the part of political leaders in committing ground troops to conflicts. When we do so, there is the inevitable demand for an exit strategy before the conflict even begins, with the admonition that we do not want another Vietnam.

Americans have a short attention span and focus when it comes to war.

A child walks near the wreckage of an American helicopter in Mogadishu, Somalia on October 14, 1993. (Scott Peterson/Liaison, Getty)

A child walks near the wreckage of an American helicopter in Mogadishu, Somalia on October 14, 1993. (Scott Peterson/Liaison, Getty)

Connected to the risk aversion is the short attention span and low tolerance for drawn out conflicts. Americans have a short attention span and focus when it comes to war. Only a short time after the success of this conflict, a perception of debacle in Somalia was followed by public demands for withdrawal, followed a few years later by President Clinton promising not to commit ground troops to deal with ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia and no military action in regards to an in progress genocide in Rwanda.

There is also the problem with a perceived lack of moral clarity in asymmetric conflicts.

There is also the problem with a perceived lack of moral clarity in asymmetric conflicts. The initial phase of Afghanistan was tied to 9/11, which seemed to provide a measure of moral clarity, but as the conflict dragged on, this justification became muddied. The 2003 intervention in Iraq was infamous for the contrived (and highly controversial at the time) moral clarity, that evaporated very quickly. Meanwhile resistance to interventions in Syria, and later Iraq again (to deal with the threat from ISIS), various locations in Africa experiencing various degrees of genocidal and ethnic cleansing issues, not to mention the crisis in the Ukraine all demonstrate the struggle with a civilian perspective with this issue of moral clarity, which many civilians see as a pre-requisite to going to war.

Finally, there is the worship of war as primarily a technological enterprise — clean, instant results, precise and bloodless.

Finally, there is the worship of war as primarily a technological enterprise — clean, instant results, precise and bloodless. The visuals and narrative of this conflict firmly established in the mind of the civilian public the idea that technology was responsible for the swift, decisive victory with very low US causalities. This sets the norms and the expectations for future conflicts; this is what war is.

I would argue, as an ethicist, that these are serious issues to engage in the public discourse on war, but all are rooted in a manufactured and unrealistic image of war as a limited, controllable enterprise in isolation from social and political factors. We hear this in the call to bomb nuclear facilities in Iran, as if this act were purely a matter of military technology. [3] This kind of call is regularly repeated every time there is some crisis or difficulty — from the civilian standpoint, we can just bomb, we can send drones or worst case send in Special Forces or other elite forces who will ‘take care of it’ and get out. It is the First Gulf War more than any other factor that shaped the idea in the mind of the US civilian population that this is possible and desirable. After all, we saw it on CNN.

Dr. Pauline Shanks-Kaurin holds a Ph.D. in Philosophy from Temple University, Philadelphia and is a specialist in military ethics, just war theory, social and political philosophy, and applied ethics. She is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, WA and teaches courses in military ethics, warfare, business ethics, and history of philosophy.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by hitting the green “Recommend” button below and sharing it on social media.

[1] The Gulf War Reader: History, Documents, Opinions. Eds. Micah L. Sifry and Christopher Cerf. (New York: Times Books, 1991), p. 228–30; 307–311.

[2] See the opening monologue on the 1970 film, Patton, starring George C. Scott.

[3] See Kenneth L. Vaux’s reflections on this in regard to the Gulf War inEthics and the Gulf War: Religion, Rhetoric and Righteousness. (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1992), p. 31.

No comments:

Post a Comment