DAVID AXE

During mock dogfights over the Pacific Ocean in January, a U.S. Air Force F-35 stealth fighter struggled to get a clean gun or missile shot at a 1980s-vintage F-16D, according to an official pilot’s report that War Is Boringobtained.

Turning the tables, the F-16 easily maneuvered behind the bulky F-35, even sneaking up on the radar-evading jet when its test pilot found his rearward view blocked by the plane’s poorly-designed canopy.

The obvious conclusion — America’s brand-new stealth fighter, which is on track to replace almost all of the Pentagon’s current fighters, is dead meat in a close air battle.

The news was shocking, even to observers long attuned to the drumbeat of design problems, test failures and budget overruns that has characterized Lockheed Martin’s 20-year effort to develop the jack-of-all-trades F-35.

But one former aviator-turned-aerospace analyst surely wasn’t surprised at all.

John Stillion predicted the F-35’s dogfight failure seven years ago in a controversial study that, by some accounts, got Stillion fired from a prominent think-tank.

What’s fascinating is not that Stillion anticipated the F-35’s poor air-to-air performance. It’s what Stillion recommended the United States do about it. The iconoclastic analyst urged the Pentagon to abandon fast, maneuverable fighters — and replace them with an entirely new kind of aerial combatant.

It was 2008. The F-35 was still in the middle of its $400-billion development. Costs had been rising and, soon, technical problems would arise that would force the Pentagon to delay the jet’s entry into frontline service by several years to 2015.

Worse — in August 2008, the RAND Corporation, a California think-tank, ran a simulated air war over the Taiwan Strait, pitting the Chinese air force against American F-22s and F-35s flying from Japan and Guam. Stillion — a former Air Force F-4 crewman — oversaw the “Pacific Vision” study along with co-author Harold Scott Perdue.

In the scenario, 72 Chinese jets patrolled the Taiwan Strait. Just 26 American warplanes — the survivors of a missile barrage targeting their airfields — were able to intercept them, including 10 F-22 stealth fighters that quickly fired off all their missiles.

That left 16 of the smaller F-35s to do battle with the Chinese. As they began exchanging fire with the enemy jets, the results were shocking.

The bulky, sluggish F-35s — over-designed in order to meet the demands of the Air Force, Navy and Marines—were no match Beijing’s warplanes. Despite their vaunted ability to evade detection by radar, the F-35s got blown out of the sky.

“The F-35 is double-inferior,” Stillion and Perdue lamented in their written summary of the war game, later leaked to the press. “Inferior acceleration, inferior climb [rate], inferior sustained turn capability,” they continued. “Also has lower top speed. Can’t turn, can’t climb, can’t run.”

Seven years later, the disheartening pilot report from the F-35’s mock battle with the F-16 would back up Stillion and Perdue’s assessment. But in 2008, such a pessimistic view of America’s trillion-dollar fighter program was divisive, to say the least. Stillion soon left RAND — a move that one Australian lawmaker called “abrupt” and “disturbing.”

But get a load of what Stillion did next. Landing at the Center for Strategic and Budget Assessments — a Washington, D.C. think-tank — Stillion authored a report proposing a radical solution to America’s fighter problem.

That is, totally getting rid of fighters as we know them.

Above — X-47B. Northrop Grumman photo. At top — F-35s. U.S. Air Force photo

Above — X-47B. Northrop Grumman photo. At top — F-35s. U.S. Air Force photo

Stillion’s “Trends in Air-to-Air Combat” study, which CSBA published in April 2015, questioned the assumptions underpinning much of the world’s fighter development.

For decades, jet-makers in the United States, Europe, Russia and China have raced to produce faster and faster fighters capable of more and more extreme maneuvers — while also endeavoring to give the planes sensor-dodging stealth qualities, among other attributes.

Those efforts have produced some eye-wateringly powerful Chinese, Russian and European fighters. But in America, the F-35’s designers never managed to strike an elegant balance — the result being a middling performer that, in any serious air battle, would get “gunned every time,”according to one test pilot.

Instead of trying to improve the F-35 or replace it with a faster, nimbler new jet, the Pentagon should rethink its obsession with speed and maneuverability, Stillion insisted. “The goal of aerial combat,” he reminded readers, “is still to achieve a victory, then get or remain outside the effective reach of a potential counterattack.”

And that goal, Stillion continued, doesn’t necessarily require speed and agility. Especially considering the tradeoffs that speed and agility demand.

“Supersonic aircraft are larger, more complex and less fuel-efficient compared to subsonic aircraft with the same range-payload capabilities,” Stillion wrote. For its part, high maneuverability is expensive and adds weight to a combat aircraft, Stillion added.

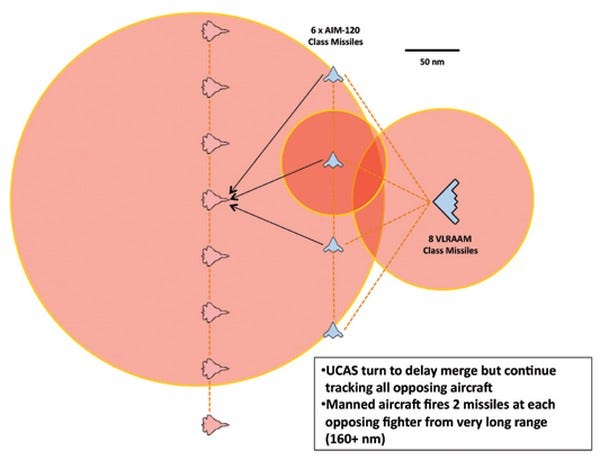

Having analyzed 1,400 air-to-air engagements between 1965 and 2002, Stillion concluded that sensors and missiles are more important than speed and maneuverability.

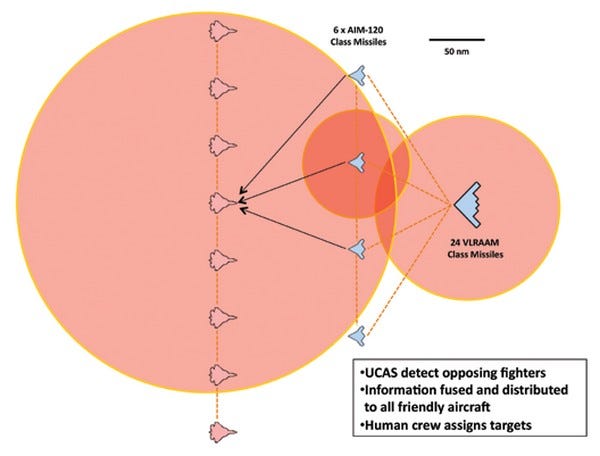

If a plane — perhaps with some drones riding shotgun—could spot its enemies far away and hit them with overwhelming numbers of far-flying missiles, it wouldn’t matter how slow and sluggish that plane was. Especially if its low speed and lack of agility bought design space for those powerful sensors and communications and huge weapons load.

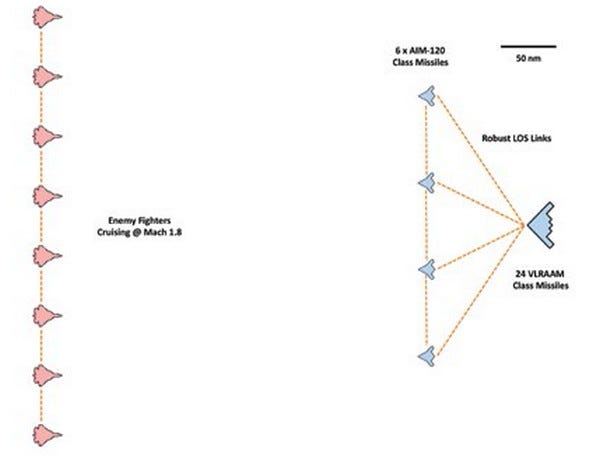

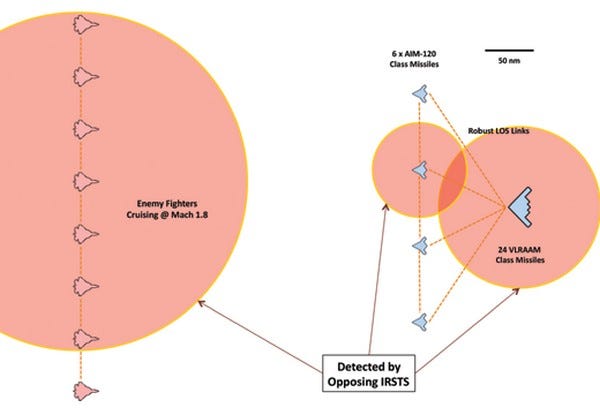

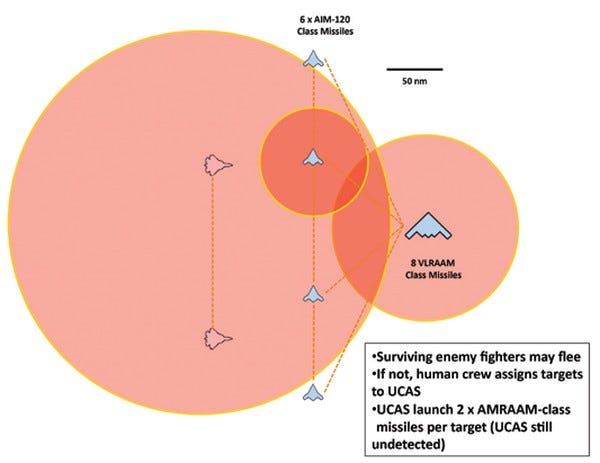

Stillion proposed an air-to-air alternative to the F-35 and other tradition fighters — a team composed of “several long-range unmanned combat air systems optimized to perform as sensor platforms with modest aerial weapon payloads that are coordinated by a human crew on board a stealthy bomber-size aircraft with a robust sensor suite.”

This “sixth-generation” fighter “may even be a modified version of a bomber airframe or the same aircraft with its payload optimized for the air-to-air mission,” Stillion added. Like a B-2 bomber armed with Phoenix missiles, flying amid a swarm of X-47Bs.

His study includes a sequence of illustrations depicting a possible future air battle pitting one of his giant fighters against traditional fast-and-nimble enemies.

Check out those illustrations below. And marvel that the analyst who first called out the F-35’s lack of speed and agility went on to conclude that, in a fighter jet, speed and agility are counter-productive, anyway.

No comments:

Post a Comment