Angry Staff Officer is a first lieutenant in the Army National Guard. He commissioned as an engineer officer after spending time as an enlisted infantryman. He has done one tour in Afghanistan as part of U.S. and Coalition retrograde operations. With a BA and an MA in history, he currently serves as a full-time Army Historian. The opinions expressed are his alone, and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Angry Staff Officer is a first lieutenant in the Army National Guard. He commissioned as an engineer officer after spending time as an enlisted infantryman. He has done one tour in Afghanistan as part of U.S. and Coalition retrograde operations. With a BA and an MA in history, he currently serves as a full-time Army Historian. The opinions expressed are his alone, and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

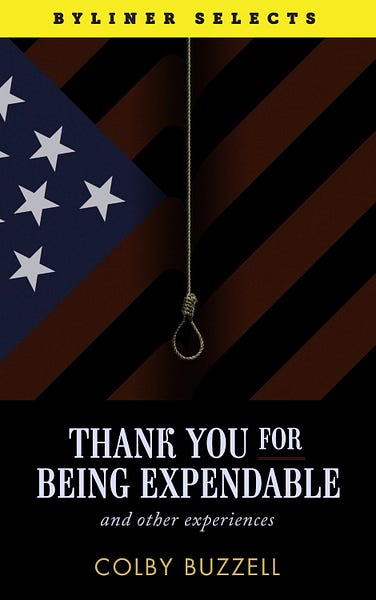

In the Army, there is a term called the “E-4 Mafia.” This refers to those who hold the rank of Specialist and who are, for better or worse, the barometer of a unit’s climate. They are sometimes team leaders or hold positions of more authority in the enlisted ranks. Most E-4’s have the particular quality of excelling at their given tasks while at the same time viewing the entire system of the military through a sardonic and skeptical lens. If non-commissioned officers are the backbone of the Army, the E-4’s are the legs. And if there actually was an “E-4 Mafia,” Colby Buzzell would be the Godfather.

From the get-go, this collection of essays might be entitled, “An E-4’s War,” because Buzzell brings the close-to-the pavement, profane, sardonic, nicotine-tinged, caffeine-fueled viewpoint that is familiar to all those in the military as the purview of the Specialist. It is a viewpoint that is often lacking in the myriad of memoirs and biographies that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan has produced. Which is a shame, because it is the E-4 who bears the brunt of the fighting. Caught in the nebulous world between lowered enlisted and junior non-commissioned officers, the Army Specialist is both incredibly proficient and incredibly jaded. Buzzell is the eternal Specialist and brings that particular mix of qualities to the page as he writes. His style is engaging, gut-wrenching, heart-wrenchingly open, thought-provoking, and tinged with rebellion. And it is impossible to put down.

Buzzell begins by explaining how he began writing, for to understand Buzzell, you first have to understand his drive to write. Writing is catharsis for him, although he does engage in other cathartic activities that involve controlled substances, as he makes amply clear. From being unemployed after 9/11 with a fear of becoming lost in “an oblivion of nothingness” to enlisting in the Army and deploying to Iraq (“If an IED exploded on Route Tampa in Mosul and nobody hears it, does it make a sound?”) to his subsequent stints as a journalist and struggles with post traumatic stress, Buzzell brings us in close and makes us one with the narrative.

…if there actually was an “E-4 Mafia,” Colby Buzzell would be the Godfather.

His topics are engaging at the personal level, and can sometimes hit home in unexpected ways. For example, he was an infantryman serving in Mosul, Iraq, and tells of hearing about the explosion inside a coalition dining facility on base, thought to be an enemy rocket. It was actually a suicide bomber, and it struck amongst members of the unit that I deployed with last. Many who survived are my friends now and have vivid memories of the blast and the ensuing chaos where two members of the unit died. It was an unexpected story that struck a nerve for me.

Buzzell does not confine himself to military topics alone; after an introduction detailing his entry, service, and exit in the military, he launches into a description of a trip to China. Then he is on to journalist assignments like chasing graffiti artists in London, traveling the US trying to get the real “state of the Union,” nude photography in the New York City subways, LSD art, and the quest for the origins of the Tamale in the deep South. Buzzell’s vivid writing style keeps the reader at his side through each piece. It is his persistence to experience life and his understanding of human nature that keeps the reader engaged.

From there, Buzzell details his up-and-down battle with post traumatic stress, living in the run-down and sometimes dangerous region of Los Angeles known as “Tenderloin.” Alcohol was his weapon as well as his enemy, as Buzzell details the struggle all too familiar to many service members. It reads painfully, and it is meant to. His work is not without bitterness, although it is tempered by Buzzell’s overpowering desire to experience life. He enjoys the experience and likes to continue to experience. It is this that drives him and makes him an incredibly sympathetic while also courageous character.

Alcohol was his weapon as well as his enemy, as Buzzell details the struggle all too familiar to many service members.

The last essays from Buzzell relate how he overcame his post traumatic stress, attended school, and became more of his whole self. He delves into how it felt for him to watch the so-called Islamic State invade Iraq and commit mass atrocities against the people he once served along with and among in Mosul. He speaks for thousands of veterans of Operation Iraqi Freedom as he remembers the interpreters who braved death to serve with the Americans, and wonders where they are now.

His conclusion brings the narrative full circle: his powerful first-person account of 9/11 at Ground Zero in Manhattan. As we again watch as the towers topple, we realize how this event will change Buzzell’s life profoundly. Without this one moment, he would not have enlisted in the Army, would not have seen combat in Iraq, would not have been burdened by post traumatic stress. It forces the reader to ask, “Was it all worth it? After seeing what happened to this one man, was it all worth it?” It is a perfect placement and conclusion to the collection.

No comments:

Post a Comment