by DARIEN CAVANAUGH

The Cuban dictator tried to breed super cows — and the CIA failed to poison his milkshake

Former Cuban dictator Fidel Castro loves milk, and especially ice cream. You could say it does a revolution good.

“One Sunday, letting himself go, [Castro] finished off a good-sized lunch with 18 scoops of ice cream,” famed novelist Gabriel Garcia Márquez wrote in his essay A Personal Portrait of Fidel.

The writer was a longtime friend and supporter of the dictator. He would occasionally recall the anecdote in interviews. Sometimes Castro ate 26 scoops, and other times it was 28. Which would sound ridiculous, if not for all the other strange stories about Castro’s love of the creamy treat.

Biographies about Castro are full of curious anecdotes, awkward diplomatic confrontations and bizarre schemes involving cows, milk and an array of other dairy products.

The dictator’s dairy crush led him to argue with a French ambassador about cheese, breed a race of super cows and on at least one occasion … it was nearly the death of him.

When Castro lived in the Havana Libre Hotel in the early ’60s, he would often enjoy a chocolate milkshake from the hotel’s lunch counter. But in 1961, the CIA hired Mafia assassins to poison the dictator’s milky meal.

Richard Bissell, then the CIA deputy director for plans, arranged to offer Sam Giancana and Santo Trafficante, Jr.— heads of the Chicago and Tampa crime families — $150,000 to help assassinate Castro with a poison pill.

Trafficante and Giancana held grudges against the dictator because he shut down Havana’s casinos, which had been lucrative businesses for them prior to Castro’s ouster of U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959.

A waiter at the hotel planned to slip one of the pills into Castro’s milkshake. Legend suggests the pill contained arsenic, but the CIA opted for a slower-acting botulinum toxin to allow the would-be assassin enough time to escape, according to CIA documents declassified in 2007.

But the waiter stored the pill in the hotel kitchen’s freezer, and it froze to the freezer’s interior lining. When the waiter tried to remove the pill, it split open and its poisonous contents spilled out.

The failed assassin abandoned the operation.

Above — the french cheese Cuba aimed to best. NJGJ photo via Wikimedia. At top — Fidel Castro treats U.S. Sen. George McGovern to ice cream in the milk-producing town of Jibacoa on May 8, 1975. Charles Tasnadi/AP photo

Above — the french cheese Cuba aimed to best. NJGJ photo via Wikimedia. At top — Fidel Castro treats U.S. Sen. George McGovern to ice cream in the milk-producing town of Jibacoa on May 8, 1975. Charles Tasnadi/AP photo

Fidel argues cheese with France

There’s few regimes in the world as invested in dairy as communist Cuba. Milk is a staple of the Cuban diet, and its production is a vital industry and relevant economic indicator.

Castro retired from the Cuban presidency in 2008, handing the reigns over to his brother, Pres. Raúl Castro. But throughout Fidel’s reign, his interest in leche betrayed both personal and political motives that he often couched in Cold War rhetoric.

For him, Cuban dairy was a symbol of the country’s “ongoing revolution” in opposition to Western and capitalist interests.

When Castro seized power in 1959, he implemented a series of economic, industrial and agricultural reforms. He oversaw many of them himself, and salvaging Cuba’s troubled milk and cattle industries became top priorities.

One of his first pet projects was to produce a superior Camembert cheese. The soft, creamy cheese is an iconic French food … and Castro wanted to do better.

When French agronomist and diplomat Andre Voisin visited Cuba in 1964, Castro urged him to confess that the new “Cuban Camembert” cheese produced on the island was superior to France’s own.

Biographer Robert Quirk summarized the exchange between Castro and Voisin in his book Fidel Castro. According to Quirk, Castro implored Voisin to try some of the new “Cuban Camembert.” Voisin complied.

“Not too bad,” the diplomat said.

This failed to satisfy Castro, and he pushed Voisin further, comparing the Cuban version to the French. Voisin agreed that it was a Camembert “in the French style” and that it was “not bad.”

“It’s like the French,” the diplomat added reluctantly.

Castro pushed further, insisting that Voisin acknowledge it was in factbetter than French Camembert. This was too much for Voisin. He slammed his fist down on the counter. “Better? Never!” he exclaimed.

Next, he reached over and pulled a cigar from Castro’s pocket. “Will you agree that there is a better cigar in the world than this?” Voisin asked. “You can’t beat tradition. My cheese and your cigars have centuries of experience behind them.”

Quirk concluded that while Castro was “pacified” for the moment, the dictator remained certain that “with intense effort and revolutionary awareness, the Cubans could surpass any country in the world in any field of endeavor.”

But the efforts to outdo the French Camembert quickly faded, and Castro focused his attention on another front — making sure Cuba had more flavors of ice cream than America.

Inside Havana’s Coppelia ice cream parlor. BitBoy/Flickr photo

Inside Havana’s Coppelia ice cream parlor. BitBoy/Flickr photo

Ice cream dream

The CIA’s failed assassination attempt did little to curb Castro’s sweet tooth. The dictator once ordered his ambassador to Canada “to ship him 28 containers of Howard Johnson’s ice cream, one of each flavor.”

After he had tasted them all, Castro declared that the “Cuban revolution must produce a quality ice cream of its own.”

Castro put Celia Sánchez — his private secretary and close companion since their days as guerrillas — in charge of opening an ice cream parlor to best Howard Johnson’s. They named it Coppelia, after Sánchez’s favorite ballet, and it opened on June 4, 1966.

Journalist Georgie Anne Geyer recalled visiting Coppelia with Castro soon after it opened in her book Buying the Night Flight: The Autobiography of a Woman Foreign Correspondent. “Castro was indeed a marvelous interview,” she recalled. “You never had to ask him a question — he began, and seven hours later, or eight, he stopped.”

She noted “one curious pause” in the conversation at around 1:30 a.m. when Castro took a breather and said, “Let’s get some ice cream.”

The two-story Coppelia, which Geyer described as “an enormous, super-modern ice cream parlor,” stood right across the street from the hotel lobby where she and Castro had met.

“We now have 28 flavors,” Castro boasted. “That’s more than Howard Johnson’s has.”

Geyer “sensed it represented more than a taste for ice cream” because “it took in a full city block, was the only modern building about and was tied to the earth by none other than flying buttresses.”

The comparison perplexed Geyer who was “astonished” and “confused” by the scene. “Was I in Communist Cuba,” she asked herself. “Or was I in Alice in Wonderland?”

“Before the revolution, the Cuban people loved Howard Johnson’s ice cream,” Castro told her. “This is our way of showing we can do everything better than the Americans.”

The parlor fit the socialist monumental style. In its heyday, Coppelia’s 414 employees served 4,250 gallons of ice cream to 35,000 patrons from 10:45 a.m. to 1:45 a.m. every day. It had four indoor salons, four outdoor cafes and one outdoor bar.

Today, Coppelia usually only offers one or two flavors, but patrons still start lining up at 10 a.m., and sometimes wait for hours to enjoy the ice cream.

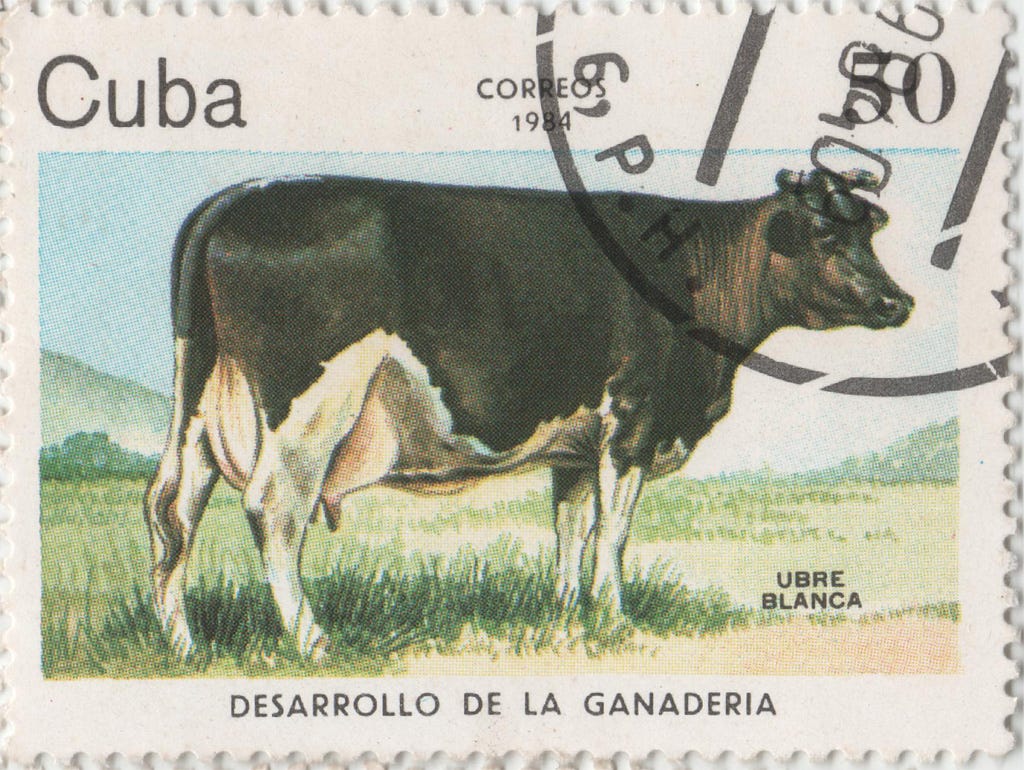

Cuba’s genetic super cow gracing a stamp. Photo via Radio y Televisión Martí

Cuba’s genetic super cow gracing a stamp. Photo via Radio y Televisión Martí

Cow of the people

After testing the waters of the dairy industry with Cuban Camembert and ice cream, Castro worked on trying to overhaul the nation’s entire dairy industry.

First, he attempted to import Holstein cows from Canada to replace Cuba’s domestic herds. When that failed, Fidel tried to breed a “super cow” that would surpass all others in milk and meat production.

In the days before the revolution, Cuba had millions of cattle, but mostwere Creoles — a breed dating back to the Spanish colonial era — and Zebus from India. Both breeds were well adapted to the steamy tropical climate of Cuba, but both were also notoriously poor milk producers.

Holsteins, on the other hand, are famed for their milk production. But the few Holsteins on the island fared poorly during the hot dry seasons, losing considerable weight and yielding substantially less milk.

Because improving milk production was necessary to the revolution, money was no object.

Cuba would simply buy several thousand expensive Holstein bulls and cows from Canada and house them in the air-conditioned facilities — such as the Nina Bonita experimental breeding farm in Cangrejeras — just outside Havana.

Nearly a third of the Holsteins purchased from Canada died in the first few weeks. Even with Soviet subsidies, trying to provide climate-controlled facilities for the nation’s entire dairy industry would be impossible.

The Holstein plan was a bust. But for Castro, the solution was obvious and simple — crossbreed Holstein or Brown Swiss cows with Zebu cows to produce a super cow that could endure the climate and produce greater quantities of milk.

Havana named the first generation of cows the F-1, the second generation F-2 … and so on. But Castro later began collectively referring to the cows as “Tropical Holsteins.”

Castro pushed on with the program throughout the ’70s and ’80s, but the numbers were against him.

The U.S. Office of Research and Policy’s 1998 Cuba Annual Report stated that while livestock numbers had briefly increased the first decade Castro was in power, they began to slowly and steadily decrease in the early ’70s.

Thousands of dairy cattle perished each year due to malnutrition and poor living conditions. But Castro’s genetic tinkering was not without small victories. For example, there was the famous cow known as Ubre Blanca, or White Udder.

Ubre Blanca was one of Cuba’s Holstein hybrids born around 1972. By all accounts, she was a giver.

The Guinness Book of Records documented the cow as producing 110 liters of milk in a single day in 1982, and 24,268.9 liters in a 305-day lactation cycle ending that same year, breaking the previous word record in both categories.

Castro seized the opportunity to appear on TV with the cow to brag about how it had achieved something no American cow could.

To be sure, Ubre Blanca was an isolated success, but she became a symbol of national pride. The communist party newspaper Granma published daily updates on her health and productivity, and featured her on its front page.

When she died in 1985, Granma ran a full obituary. “She gave her all for the people,” wrote Pastor Ponce, an agronomist with Cuba’s National Cattle Health Center.

Castro commissioned a marble statue of Ubre Blanca, ordered geneticists to take her eggs and preserve tissue samples at the country’s Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology. Had her stuffed and put on permanent display at the National Cattle Health Center near Havana.

Her statue still stands in the rural town of Nuevo Gerona, her hometown, near a spot where she once grazed.

A Dexter breed mini-cow in the style Castro wanted. David Merrett photo via Wikimedia

A Dexter breed mini-cow in the style Castro wanted. David Merrett photo via Wikimedia

Mini-cow in every closet

After the death of Ubre Blanca, the rest of the Tropical Holsteins continuedproducing modest quantities of milk. But none of Ubre Blanca’s seven offspring were prodigious. The program lingered, and excessive numbers of Cuban dairy cattle continued to die each year.

Castro often attributed these failures to the United States. He blamed the U.S. trade embargo, and spun theories that an American chemical and biological attack was responsible for the declining cattle.

Embargoes and theories of biological warfare aside, the revolutionary government realized they needed new ideas. If super cows wouldn’t work, then perhaps they could go in another direction.

In 1987, Castro asked his scientists to produce mini cows “the size of dogs.”

Boris Luis Garcia — a scientist who worked on the project — told The Wall Street Journal that the plan called for breeding cows small enough to keep inside an apartment, yet productive enough to provide milk for an entire family.

The mini cows would feed on grass grown in drawers under fluorescent lights. “That was what Castro had planned for us,” Garcia explained.

Nothing came of the mini-cow scheme, but Castro still had one last trick up his sleeve for solving Cuba’s milk crisis.

Inspired by the successful cloning of Dolly the Sheep in Scotland, he ordered his scientists to take Ubre Blanca’s preserved tissue samples and clone her.

“If we discover a technique — if another Ubre Blanca is found, or a prodigious descendant of Ubre Blanca — what can prevent us from immediately applying this practice everywhere across the country, to all the cows of Cuba?” Castro said in a 1987 speech.

“We’re very close … we have big things coming,” Jose Morales, the director of the cloning project, said in 2002. “This project is very important toComandante Castro.”

Today, Cuba still suffers from milk shortages. An army of cloned cows is nowhere on the horizon.

But U.S.-Cuba relations have improved. In 2000, Pres. Bill Clinton reformed agricultural trade relations with Havana. America is now one of the biggest suppliers of food and cattle to Cuba.

In December, Pres. Barack Obama and Cuban Pres. Raul Castro announced the two countries would begin normalizing relations. Meanwhile, Fidel still lives — as does his milk obsession. Anecdotes about his bizarre lactose fixation persist.

In the early 1970s, Chilean envoy Jorge Edwards traveled to Cuba. While he was there, Castro forced him to try milks from many different cows. The dictator insisted he could discern the finer differences between each creature’s output.

“It was impossible to determine to which cow … the milk had come from,” Edwards explained in the documentary The Last Communist.

“To top it off, in some jugs, milk from different cows had been mixed up. And so we had a sort of very strange orgy of drinking milk.”

No comments:

Post a Comment