Nathan Wike is an officer and a strategist in the U.S. Army. The opinions expressed are his alone, and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government

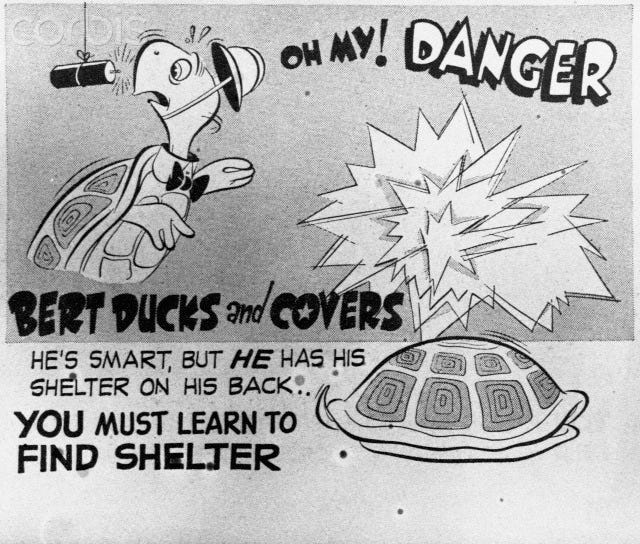

There has been much ado recently about toxic leaders and their immediate effects on their environment. Like the first seconds of a nuclear explosion, witnesses report seeing a blinding flash of incompetence, risk-aversion, or antagonism. They hear a defining roar like a furnace spewing conflicting guidance, vague directives, and unclear intent. The shock wave advances, enveloping impressionable young leaders and experienced older leaders alike. The ground shakes with the coming of the toxic leader as all who are within the blast radius desperately attempt to seek cover by looking busy or disappearing behind a container in the motor pool. Toxic leaders advance through the ranks of the military, leaving destruction in their wake. They could be anyone from the soldier sporting a new set of corporal’s stripes to a commanding general. Oftentimes they do not realize that they are toxic — that their leadership style is what it is and subordinates need to fall into line. Just as frequently they do not realize or appreciate the power of their toxicity, nor the lasting damage they may have on the organization.

The immediate effects of a toxic leader, like a nuclear blast are nothing short of awesome. Victims who are not immediately consumed are left dazed and confused at what just occurred. With just a few words, the toxic leader may have undermined the authority of a platoon leader, usurped the responsibilities of a non-commissioned officer, or eroded the confidence of a soldier. Entire operations, meetings, and briefs grind to a halt. How could any one person be so erroneous, unreasonable, or indecisive? Why did the government allow the creation of weapons capable of such wanton destruction?

But what of the more insidious residual effects? The shock wave has passed — the toxic one has moved on, been relieved, or has disappeared back into their office. Exactly what constitutes toxicity is difficult to define, though it has been well covered in posts by other, much better informed authors. Yet a topic that has only just started to garner notice are the long term effects of a toxic leader on an individual and an organization. As a leader one is expected to be a steward of the profession. But if a leader is toxic, their judgment and their guidance is at best not to be trusted. This brings into question all their decisions, advice, recommendations, and their very legacy. It is a question that may echo through the future across multiple organizations and the careers of multiple individuals. How can one be expected to survive and thrive in the environment they have left in their wake?

The army defines leadership as “the process of influencing people by providing purpose, direction, and motivation to accomplish the mission and improve the organization” (ADP 6–22). It stands to reason then, that a toxic leader fails in one or all of those precepts — they fail to influence effectively, provide little or no purpose, lack direction, are unable to motivate soldiers to accomplish a mission, and fail to improve the organization. Furthermore, by their very nature they are not mentors — and if they believe they are, they are a poor substitute.

They exert influence through intimidation, coercion, and obsequiousness. Deceit and hypocrisy are tools used to further their own ends as they justify their actions to subordinates, peers, and superiors alike. When the boss is around, they may be as suave and charming as a used car salesman. But when there is no oversight, the gloves come off. Toxic leaders rely on soldiers and junior leaders to want to do the right thing — to follow their oaths, creeds, and the army values and obey the orders of those appointed over them. They need for everyone beneath them to believe they are working for the greater good of the organization that speaking out would be disloyal and selfish, and would undermine good order and discipline. Taking advantage of soldiers (of any rank) in this way causes them to become jaded, resentful, and forlorn. Consciously or unconsciously they may begin to learn the wrong ways to exert influence, adapting the techniques of a toxic leader to their own leadership style, thereby running the risk of becoming toxic themselves.

The toxic leader does not provide their unit with a clearly defined end state or a reason to perform well. They either provide no oversight, or micromanage to the point that junior leaders become apathetic or overwhelmed. Because they do not know how to influence, a toxic leader also does not know how to motivate. Both high and low performing individuals are rewarded equally. Soldiers are benumbed by a slew of orders without being provided that critical spark of knowledge that generates understanding, then motivation to accomplish a task in support of a mission. Some of the most talented junior leaders begin to look for greener pastures, in another unit, branch, or in the civilian world and now one sees them slipping and provides an incentive to stay.

Organizations often fail to improve under a toxic leader — if they do improve it is only in fits and starts as the toxic leader mercilessly drives subordinates to complete a task, or gain an achievement. Anything that is gained is quickly lost however as soldiers and leaders become dazed followers, avoiding any semblance of initiative for fear of retaliation or out of a spirit of vengeance. Toxic leaders do not take the time to ingrain a sense of duty and responsibility, or to embody a precept of mission command that soldiers perform the correct actions in the absence of orders. The culture of the organization erodes, and soldiers going forward look back with resentment and reluctance to act due to their traumatizing experience. The hopefully HAZMAT certified follow on leaders must focus all their time cleaning up the toxic leader’s mess, rather than creating a legacy of their own.

Toxic leaders are mentors of dubious quality. They tend lack the requisite knowledge and experience, provide guidance and advice which serves their own interests or that is factually incorrect. The mentor-mentee dynamic becomes a quid pro quo relationship of the worst sort — the toxic mentor takes all the mentored has to give and offers scant reward in return. Or they may not make any sort of effort to be a mentor at all , allowing quality leaders to wither in despair and exit the force, or similarly toxic junior leaders to continue to advance unimpeded. Quality leaders who remain have their development retarded as they do not get the guidance they need to excel. Toxic junior leaders mutate and thrive as their actions are reinforced by lack of direction, or their supervisor’s own example. Perhaps worst of all, any other leader may potentially become warped, turning into the same sort of toxic leader they once despised.

The military has a vested interest in rehabilitating and eliminating toxic leaders as soon as they make themselves known, and it is vital that such leaders become known as soon as possible. Part of this in on subordinates, who should not be afraid to be brutally honest on their command climate surveys, MSAFs, or to utilize the office of the inspector general, a chaplain, or the appropriate open door policy. Another part of this is on peers, who should be comfortable opening a dialogue with a toxic leader and encouraging them to adopt more beneficial methods of leadership and be willing to take concerns to the next level of command. But the preponderance of the responsibility for phasing out toxicity in the military is split between the individual and their supervisors.

A toxic leader’s supervisor should not hesitate to provide honest, candid feedback. Supervisors should record the performance of a toxic leader, or lack thereof and warn them as they stray from the path. As painful as it is, keeping the long term benefits of the force in mind, a supervisor must be prepared to write an appropriate evaluation that either stops a career in its tracks or shakes it to the point where change is forced. It is doubtful that any individual consciously wants to be toxic —again it may be they do not know they are toxic. Yet once they are made aware, they should make every effort to change. This means reading, soliciting feedback, utilizing free tools such as the coaching offered on the MSAF website, or removing themselves to positions where they cannot poison the force. Regardless of what it takes, a toxic leader must realize that their toxicity has no place in the military.

For various reasons, toxic individuals are allowed to assume the mantle of leadership and become responsible for soldiers, NCOs, and officers, and for fostering the next generation of leaders. If allowed to remain, they spread toxicity like a cancer, infecting others and creating an inhospitable environment for all. No one wants to work for a toxic leader, and if they work for one they say “never again”. Toxic leaders are more than just a problem for the moment — their residual effects poison the future and poses a danger to the credibility and values of the entire force. Good units, when a new leader arrives, should always give that person the benefit of the doubt. If and when that person begins to exhibit symptoms of toxicity, it is the obligation of everyone in the kill zone to stop the blast before it occurs and thereby avoid the inevitable fallout.

No comments:

Post a Comment