This post was provided by Dr. Lawrence Freedman, Emeritus Professor of War Studies King’s College London. His latest book is Strategy: A History.

This note comes in response to a request for observations on the efficacy or otherwise of non-violent strategies. The arguments for strategies that work without resort to violence are self-evident: taking up violence against a stronger opponent often leads to a bloody crackdown; even successful violence can be brutalising and comes with a high human cost; it is much easier to achieve reconciliation if no violence has been used. There is also a moral side to non-violence, reflecting the pacifist origins of some key proponents. The tendency more recently has been to take a more pragmatic approach, and demonstrate that non-violence can really “work”. This view got a boost with the early days of the Arab Spring, although sadly that boost looks less secure now.

We can accept that a non-violent strategy should be followed when facing a non-violent opponent. The challenge comes when facing a strong state apparatus ready to resort to violence to protect its position. In these circumstances following a path of non-violence can be both futile and dangerous. Rather than identify the circumstances in which such a strategy can nonetheless succeed I want to offer a different approach here, which is to accept that in violent situations a readiness to resort to violence in response is an unavoidable part of the equation. There are often competing factions within the same political movement, each pushing a different strategy. A decisive rejection of one strategy may result in splits and dissension.

So the use of violence, as with non-violence, has to be judged with regard to its political effects, which means building bridges with potential allies, isolating opponents and identifying paths forward to a negotiated resolution of a conflict. To accept a role for violence does not necessarily mean pushing a conflict to a bloody conclusion. In this regard Nelson Mandela’s approach to the role of violence in strategy is instructive. He explicitly abandoned non-violence yet managed to orchestrate a relatively peaceful transition to majority rule in South Africa.

The comparison with Martin Luther King is also instructive. In the late 1950s both King and Mandela were rising stars in political movements influenced by Gandhi, dedicated to non-violent struggle against racial oppression. Both eventually could claim some success and saw this marked by the awards of the Nobel Peace Prize. Yet there was an important difference. King never deviated from the path of non-violence though he (like Gandhi) died a violent death, assassinated in 1968. Mandela died peacefully as a revered international leader, yet by 1960 he had turned to armed struggle.

March on Washington, Aug 28, 1963

March on Washington, Aug 28, 1963

King gained his leadership role in part as an extension of his religious position as a Baptist Minister and then had an organisation — the Southern Christian Leadership Conference — created around him. Mandela had to make his way within an established political party — the African National Congress — in which there were a number of strands of opinion. King had a target audience in the US Government who in the end could push aside the Jim Crow laws imposed by the Southern white establishment. Mandela had a much harder task in persuading the Nationalists to relinquish their power. The international community might put pressure on the South African whites but they could not force them to abandon Apartheid. Lastly, during the late 1950s King was chalking up some tangible successes, starting with the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott. Mandela could only see the Apartheid laws tightening, backed by increasing violence.

by acting with dignity and restraint against authorities for whom brutality appeared as a default mode they made their cause appear nobler

For King non-violence was a moral imperative, but its adoption depended on two important strategic advantages. First, against a well-armed opponent it was prudent. In a straight fight his people were likely to lose. Second, by acting with dignity and restraint against authorities for whom brutality appeared as a default mode they made their cause appear nobler. The methods depended on mass mobilisation, with strikes, boycotts and demonstrations — both to show widespread popular support and provoke the authorities. It was often remarked that King’s strategy worked best when there was a brutal local sheriff to provoke. In this respect, as critics observed, the success of the civil rights movement depended on violence, except that rather than inflicting violence it involved presenting peaceful people as victims.

II

King came to non-violence during the course of his early struggles. Mandela inherited it. Gandhi’s first experiments with non-violent civil disobedience had occurred while he was a lawyer in South Africa. His legacy in the country remained strong. The head of the African National Congress, Chief Albert Lutuli was an explicit proponent of non-violent methods. On this basis he was awarded the 1961 Nobel Peace prize. By this time Mandela had abandoned this approach. As an activist he had not questioned the non-violent approach. A far bigger issue for him initially was whether the ANC should be a Black Nationalist organization or should be prepared to forge a popular front with Indians and whites, including communists. In 1951 Mandela, previously a Black Nationalist, did a complete U-turn and accepted that Africans must work with others.

Mandela, however, was aware that white South Africa was more than a small settler community but a large section of the population that would eventually have to be reconciled with majority rule.

The refusal of the ANC to adopt an exclusive approach led to a breakaway movement — the Pan-African Congress. The PAC was more in tune with the anti-colonial movements — and governments — elsewhere in Africa. Mandela, however, was aware that white South Africa was more than a small settler community but a large section of the population that would eventually have to be reconciled with majority rule. This readiness to work with others was a constant in his strategic approach, as was his commitment, from this point, to a democratic and non-racial state.

Yet he also concluded that the ANC must go beyond non-violent civil disobedience, especially in conditions where that was becoming harder to organise and dangerous to execute. In the fevered atmosphere after the March 1960 Sharpeville massacre, when 69 Africans were killed demonstrating against the pass laws and then the ANC and PAC were both banned, any radical group that was reluctant to accept armed struggle of some sort risked being left behind. A number of groups, often without a clear institutional identity, began to meet and conspire. Although the ANC was still officially non-violent, Mandela was the first to go out on a limb publicly. He said that if the government intent was “to crush by naked force our nonviolent struggle, we have to reconsider our tactics. In my mind we are closing a chapter on this question of a nonviolent policy”.

An unlocated photo taken in South Africa in the 1950s shows supporters of the African National Congress (ANC) gathering as part of a civil disobedience campaign to protest the apartheid regime of racial segregation | AFP/Getty Images

An unlocated photo taken in South Africa in the 1950s shows supporters of the African National Congress (ANC) gathering as part of a civil disobedience campaign to protest the apartheid regime of racial segregation | AFP/Getty Images

At his trial in 1964 Mandela explained that one reason why he felt that the ANC had to abandon strict non-violence was to control the violence:

“Unless responsible leadership was given to canalise and control the feelings of our people, there would be outbreaks of terrorism which would produce an intensity of bitterness and hostility between the various races of this country which is not produced even by war.”

To stay ahead of the movement the ANC had to follow the trend. It was about keeping control of the struggle as much as coercing the government. This is not unusual. If the ANC had not done anything the field would have been left open for the PAC or any number of new groups.

By this time it now seems to be the case that Mandela had joined the South African Communist Party and was serving on its central committee. This was always denied for political reasons and remains a bit murky. Recent research tends to confirm his role, and also that the leadership of the party decided during that year to adopt a policy of armed struggle. At the end of 1960 the Central Committee was instructed “to devise a Plan of Action that would involve the use of economic sabotage”. In June 1961 he raised the issue at the ANC Executive and persuaded Chief Luthuli that this was now inevitable. In effect the movement was to be divided into two — a political party with a military wing. The mainstream leadership had to distance itself from any military activity. Thus what came to be called Umkhonto we Sizwe, Zulu for “Spear of the Nation”, known by its abbreviation MK, was to be a separate and independent organ, linked to ANC and under overall ANC control but autonomous. The government was warned that if it did not take steps toward constitutional reform and increase political rights there would be retaliation. MK launched its first guerrilla attacks against government installations on 16 December 1961 with 57 bombings. The plan was to attack economic and government targets while, as much as possible, avoiding loss of life. The presumption was that if these more modest tactics failed then the next step would be to move to guerrilla warfare and terrorism.

Mandela sought a controlled form of violence, to ensure that it served political demands and did not become all-consuming in itself. This explains the initial focus on economic sabotage. Two of those closest to Mandela, Joe Slovo and Walter Sisulu, observed that: “Our mandate was to wage acts of violence against the state — precisely what form those acts would take was yet to be decided. Our intention was to begin with what was least violent to individuals but most damaging to the state.”

“I, who had never been a soldier, who had never fought in battle, who had never fired a gun at an enemy, had been given the task of starting an army.”

It is clear that Mandela had no idea how to lead an armed struggle. “I, who had never been a soldier, who had never fought in battle, who had never fired a gun at an enemy, had been given the task of starting an army.” He needed to act quickly if the ANC was going to exert leadership though the advice from the Chinese and North Vietnamese was that armed struggle took time and appropriate conditions, and that these were probably not in place. Here, not uniquely, Mandela took comfort from the recent Cuban revolution. This was already creating its own mythology about how a relatively small force of brave men — the foco — could itself create the conditions for insurrection without having to wait until they appeared on their own accord. There was at the time some optimism that it was only a matter of time before the edifice of apartheid began to collapse. Colonialism was crumbling in the face of one liberation struggle after another. The regime’s hold on power was assumed to be fragile.

Mandela did all he could. He not only looked at Cuba but also the Boer War, and the tactics of Jewish fighters against the British in Palestine the mid-1940s. (Remember that his white comrades in this struggle were disproportionately Jewish and some had experience in Israel). He read about China. As he thought about targets he examined South Africa’s infrastructure and industrial organisations, its transportation system and communications. He also got training from Algerians. So he learnt how to use weapons and set off explosives. The course was supposed to last six months but after only two he was told to return to South Africa to get things moving.

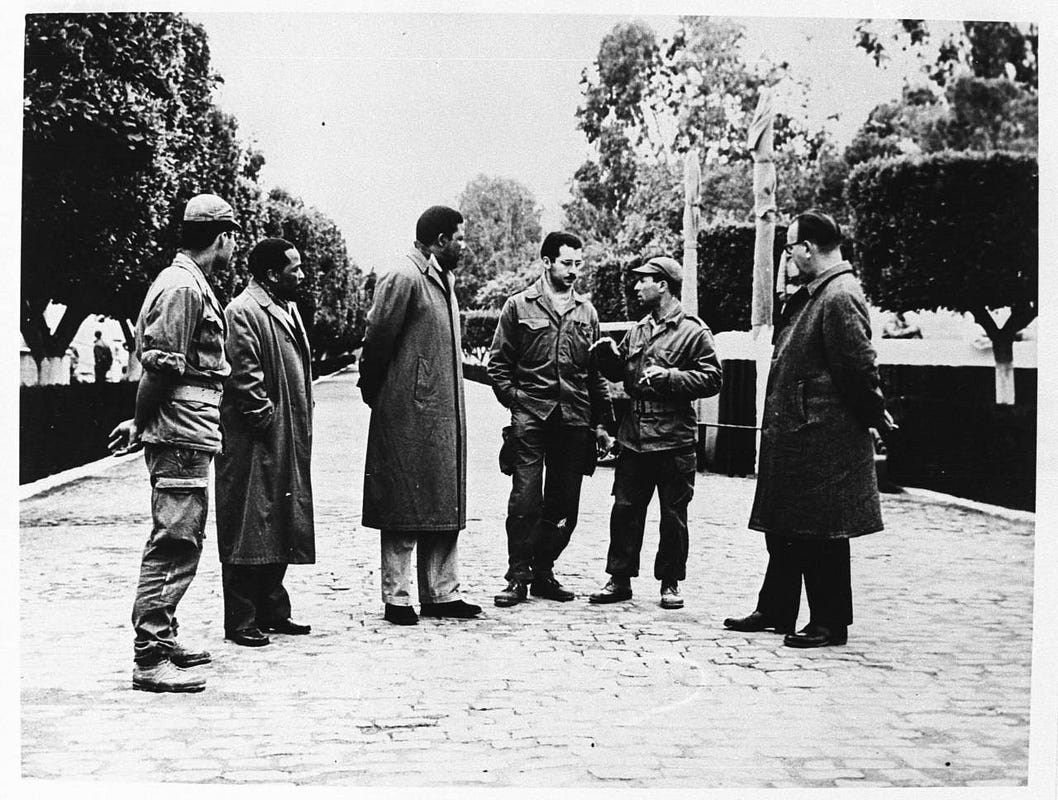

In 1962 Mandela spent time in Morocco and Algeria where he received military training. He also raised money from countries like Egypt, Ethiopia and Tunisia during travels in the Maghreb region in 61–62.

In 1962 Mandela spent time in Morocco and Algeria where he received military training. He also raised money from countries like Egypt, Ethiopia and Tunisia during travels in the Maghreb region in 61–62.

When we read Mandela’s own account of his revolutionary education he appears as an ingénue, excited at meeting people who had been successful in their struggles. At any rate Mandela’s campaign as a revolutionary leader did not last long. The plan was to go for He was arrested on 5 August 1962. There are different reasons for why he was quickly arrested — some blame the CIA but Mandela blames himself for leaving too many clues. It all now looks rushed and amateurish.

The Rivonia trial began on 9 October 1963 with Mandela and his comrades charged with four counts of sabotage and conspiracy to violently overthrow the government. The case was thrown out, but charges reformulated. Witnesses presented from December until February 1964. Mandela and the accused admitted sabotage but denied that they had ever agreed to initiate guerrilla war against the government. They used the trial to highlight their political cause. On 12 June 1964 Mandela and two of his co-accused were found guilty on all four charges, but sentenced to life imprisonment rather than death.

It is at this point worth pausing and contemplate Mandela’s reputation had the expected death penalty been implemented. He would now be remembered as yet another leader cut down in his prime, another Lumumba or Che Guevara, a romantic quasi-Marxist whose enthusiasm outweighed his capacity.

III

Instead, as a result of his trial Mandela had an international as well as a national profile. While clearly the victim of an unjust system he was not actually dead. He was not even the leader of the ANC but clearly a leader in waiting. This was understood at the time — in a way prison would protect him until the time was ripe and he could be released to play the statesmanlike role for which he had been preparing himself. Nobody knew it would take 27 years. Over that period he made no public appearances or speeches. Initially he was barely able to communicate at all. Nobody — other than his closest associates — knew what his views were. As the years passed it was not clear whether he would have much of value to say — did he understand what was going on within South Africa, the political currents at play? How did he relate to a much more radical and bitter younger generation? So over time he became a symbol of a past injustice but also an enigmatic future opportunity.

The most consistent part of his strategy was his belief in coalitions and the goal of a democratic and non-racial South Africa.

Meanwhile, as is often the case when groups of dissidents are gathered in prison, even when they are from opposing factions, they tend to forge new groupings. The prisoners at Robbin Island educated each other and debated topics. Mandela studied Afrikaans — initially to gain respect from his warder. It became another weapon in his armoury. In 1967 prison conditions improved and by 1975 his status had been raised and he had more visitors, studying for LLB and writing his autobiography. By now he was relatively more moderate — critical of the racism as he saw it of the black consciousness movement and of their criticism of anti-apartheid whites. The most consistent part of his strategy was his belief in coalitions and the goal of a democratic and non-racial South Africa.

In 1982, along with other ANC leaders he was moved to Pollsmoor Prison. By now the country was becoming more violent, and the international sanctions campaign was building up. Companies were finding it hard to justify investments in South Africa. In February 1985 President Botha offered him a release from prison if he ‘”unconditionally rejected violence as a political weapon”. Mandela spurned the offer, releasing a statement through his daughter Zindzi stating “What freedom am I being offered while the organisation of the people remains banned? Only free men can negotiate. A prisoner cannot enter into contracts.”

This remained his position, and shows how he understood that the violence did give the ANC a degree of leverage in the situation. He was by now looking for a way forward. In 1985 Mandela after surgery on an enlarged prostate gland and in new solitary quarters on the ground floor at Pollsmoor, he reached an important conclusion. His description of it constitutes a remarkable piece of strategic reasoning and is worth quoting in full from his memoir:

“My solitude gave me a certain liberty, and I resolved to use it to do something I had been pondering for a long while: begin discussions with the government. I had concluded that the time had come when the struggle could best be pushed forward through negotiations. If we did not start a dialogue soon, both sides would be plunged into a dark night of oppression, violence, and war…It simply did not make sense for both sides to lose thousands if not millions of lives in a conflict that was unnecessary. They [the government] must have known this as well. It was time to talk. This would be extremely sensitive. Both sides regarded discussions as a sign of weakness and betrayal. Neither would come to the table until the other made significant concessions…Someone from our side needed to take the first step, and my new isolation gave me both the freedom to do so and the assurance, at least for a while, of the confidentiality of my efforts. I chose to tell no one of what I was about to do. Not my colleagues upstairs or those in Lusaka. The ANC is a collective, but the government had made collectivity in this case impossible. I did not have the security or the time to discuss these issues with my organization. I knew that my colleagues upstairs would condemn my proposal, and that would kill my initiative even before it was born. There are times when a leader must move out ahead of his flock, go off in a new direction, confident that he is leading his people the right way. Finally, my isolation furnished my organization with an excuse in case matters went awry: the old man was alone and completely cut off, and his actions were taken by him as an individual, not a representative of the ANC.”

This deserves to be read as a classic of negotiating strategy. It has a sense of ripe time — a zero-sum conflict is turning into a non-zero sum, in which both can lose or both can win, in this case according to whether the violence can be controlled. The barrier to an agreement is seen to be getting talks started because both sides have come to regard talks as “a sign of weakness and betrayal.” He saw his unique position as one who could take a lead, because he had excuses for not gaining approval from his ANC colleagues. At the same time this lack of approval meant that he could tell the government that he could not make unreasonable concessions and, if the effort failed, could be readily repudiated without damaging the ANC. This strategy worked because Mandela was ready to risk being denounced as a traitor to the cause for which he had devoted his life.

It took almost five years to get to the desired result. Nothing came of this initially except that he now had a contact in the government — Minister of Justice Kobie Coetsee. He saw this contact as an olive branch. From this point on it became a question of how proper negotiations might begin, which took another two years, after which it took yet another two before there were real breakthroughs. Note that when in 1988 an offer was made by the government to release political prisoners and legalise the ANC on condition that it permanently renounced violence, broke links with the Communist Party and did not insist on majority rule, Mandela rejected these conditions. He would only end the armed struggle when the government renounced violence.

He would only end the armed struggle when the government renounced violence.

It is always dangerous to draw general lessons from specific cases — whether the American civil rights movement or the ANC. The Mandela case does show, however, that once non-violence has been abandoned it does not mean that the only option is all-out war. Mandela always understood the limits to violence and sought to contain its effects, but he never doubted that it was an extra source of pressure on an illegitimate government.

Sources

Nelson Mandela, The Long Walk to Freedom (London: Little, Brown & Co, 1994).

Nelson Mandela, Conversations with Myself, (London: Macmillan, 2010).

Anthony Sampson, Mandela: The Authorised Biography, ( London: HarperCollins, 2011).

Stephen Ellis, “The Genesis of the ANC’s Armed Struggle in South Africa 1948–1961.” Journal of Southern African Studies 37 (4), 2011: 657–676.

James Read, “Models of Leadership and Power in Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom”, Paper delivered to the American Political Science Association August 31-Sept. 3, 2006.

No comments:

Post a Comment