Retired General Colin L. Powell, appearing as part of the National Geographic Channel documentary series, “American War Generals”

Every time I read another armchair strategist comment on the irrelevance of Clausewitz in contemporary conflict, I’m left shaking my head. In many ways, reading “On War” is like reading the Bible: literal interpretations of the text often lead readers to misinterpretations of the deeper, often hidden meanings of the passages. Recognizing and understanding the context of the writing is essential to developing an understanding of the concepts within.

Context is everything.

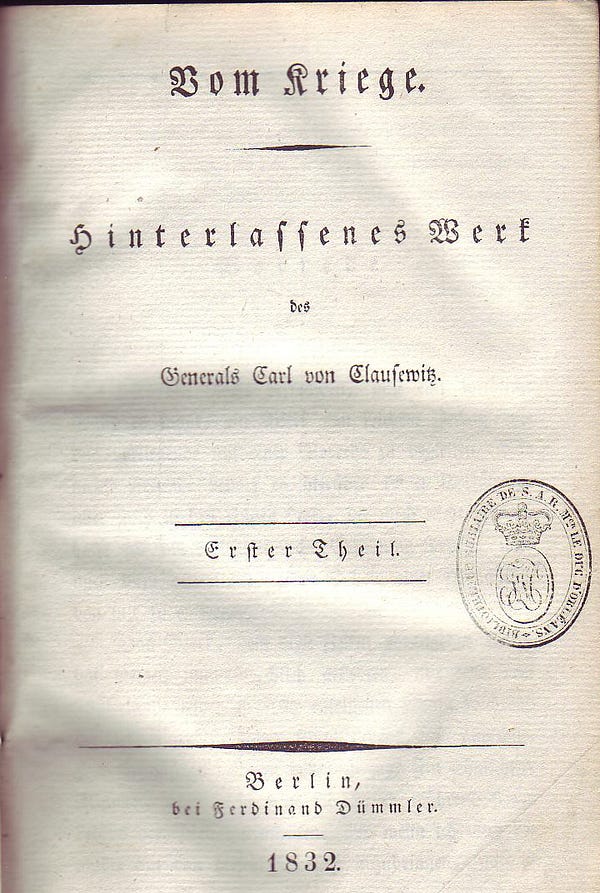

Title page of the original German edition Vom Kriege, published in 1832.

People like to say that Clausewitz is the least read, most quoted of the military theorists. His writing isn’t as pithily quotable as Sun Tzu or as provocatively diabolical as Machiavelli. It is steeped in metaphors, written in the years after the Napoleonic wars as Clausewitz struggled to grasp the elusive taxonomy required to describe complexities of early 19th century maneuver warfare, and war in general. For years, he was on the receiving end of some of the French emperor’s greatest campaigns, the so-called business end of the “tip of the spear,” where lessons often come hard and fast. Yet today, nearly 200 years after its publication in 1832, we’re still studying and debating the merits of On War.

It’s all about the context.

So, it was with some amusement that I read retired Army colonel Philip Lisagor’s post, “Don’t Bring Back the Powell Doctrine,” in Cicero Magazine earlier this week. His interpretation of the Powell Doctrine is quite literal (“The Powell Doctrine sets a standard too high to justify action against the majority of threats America faces today.”), yet he still manages to invoke Clausewitz (“… understanding the nature of the war one is facing is paramount.”). His translation of Powell’s eight “questions” is too simplistic to convey the original intent adequately, sort of like studying a pidgin English interpretation of Clausewitz. Ultimately, his argument against the Powell Doctrine can be summarized in one telling passage:

The problem is that the Powell Doctrine is a pair of zip-lock handcuffs when it comes to dealing with threats such as terrorism and insurgencies today. It sets us up to be either “all in or all out.” We must either commit the full of our national might and energies to a war or we should do nothing at all.

I don’t fault Lisigor’s attempt, I fault his logic. I fault his approach and his analysis. But, to be fair and honest, I carry a fair amount of bias. I have been a long and unapologetic proponent of General Colin Powell’s extrapolation of the originalWeinberger Doctrine, conceived by former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger.

Like On War, the Powell Doctrine demands an understanding of context. The roots of the Powell Doctrine trace back to the American experience in Vietnam, and bear the visible scars of that war. And, like Clausewitz, applying the Powell Doctrine requires the intellectual capacity to overlay the original context onto a contemporary security environment. You have to think broader, deeper, and outside the bounds of the temporal context. Think figuratively, not literally. It is not a checklist, but a menu for critical analysis and strategy formulation.

Everything comes down to context.

Lisagor dismisses the Powell Doctrine. Formulaic. Inflexible. Symmetric. A relic of the Cold War. All of which is true, unfortunately, if you don’t expand your thinking beyond the bounds of the original context. Quite frankly, if you want to apply the Powell Doctrine in a modern context, you have to be able to “extend your game” in time and space. The Powell Doctrine is, in my opinion, a timeless framework for Grand Strategy. It closely mirrors the Design methodology, providing the broad perspective necessary to take the “long view” of a situation and determine how best to apply the full range of instruments of national (and international) power.

Is a vital national security interest threatened? A fair opening question, and one that should always be answered before committing the blood and treasure of the Nation. That doesn’t mean that action won’t be taken if the answer is no, it just provides a foundation for further analysis.

Do we have a clear attainable objective? This is where most thinking goes astray. Clearly defined, attainable objectives are non-negotiable if you ever hope to achieve any degree of success, and they are absolutely sacrosanct if you intend to define success. But objectives are also transitory, meaning they will change over time and will have to be revisited iteratively as the strategic process matures.

Have the risks and costs been fully and frankly analyzed? The Ends-Ways-Means-Risk formula for strategy isn’t a linear equation. It’s a differential equation. If you didn’t make it that far in math, you are probably already out of your league. To apply the Powell Doctrine with success, you have to be able to think and plan across multiple dimensions, and you have to have a grasp of how the balance and interplay across the Ends-Ways-Means-Risk formula ebbs and flows in time and space. This is one principal reason why Grand Strategy seems so elusive: if you can’t master the mental modeling behind the equation, you’ll never have a firm grasp of the risks and costs associated with action.

Have all other non-violent policy means been fully exhausted? Every military theorist from Captain Caveman to Sun Tzu recognized that violence should only be used as a last resort. Never lead with your best punch, dance with your opponent first. To paraphrase strategist Frank Hoffman, I can give you 7,000 current, relevant reasons why this is essential to any effort. Before we commit blood and treasure, every other option must be explored. We owe that to ourselves and to our country.

Is there a plausible exit strategy to avoid endless entanglement? Never enter a hostile room unless you know where all the exits are. An exit strategy isn’t a date on a calendar. It’s a set of conditions, framed with objectives. Those conditions may change over time, but it’s imperative to have a relatively clear view of what “success” looks like (and a plan to get there) before you decide to pull chocks, unass the AO, or di di mau. The rise of ISIS is a cautionary tale of the consequences of confusing a plausible exit strategy with a date on the calendar.

Have the consequences of our action been fully considered? An appreciation for Newton’s Third Law is also important: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. And keep in mind that the reaction you get probably won’t be the reaction you planned for, nor will it occur when you’re expecting it. That’s why extending your thinking in time and space is so important.

Is the action supported by the American people? In our society the link between the people, Congress and the military is irrefutable. If the people don’t support the actions of the military, the political will for action will erode over time. And the attention span of the nation really isn’t all that long, so any extended conflict will increasingly come into question, especially a conflict in which they don’t perceive a threat to national security.

Do we have genuine broad international support? Unilateral action is a lot like farting in church — everyone knows you did it, and nobody likes it. It’s always preferable to bring as many of your friends to the party as you can manage, especially if they’re willing to shoulder a portion of the load. The more the merrier, I say.

The most common criticism of the Powell Doctrine is the “overwhelming force” caveat (if you’re in it, you’re in it to win it). Again, think in terms of context. Just as Clausewitz penned On War before the days of industrial age warfare, the Powell Doctrine was conceived before the advent of digital age (and information age) operations. Force shouldn’t be constrained to mental images of kinetic action, and doing so only limits the available options. But if you’ve committed to military action, overwhelming force (however that is defined) is essential in the inevitable clash of wills. (This could easily lead to a lengthy discussion on the interdependent nature of the principles of war and the fact that they are principles for a reason).

At the end of the day, the Powell Doctrine applies whether you’re planning the invasion of some distant third world power or preparing for the mother of all interventions into terrorist-held territory. It sets the analytical framework necessary for Grand Strategy, ensuring due diligence in the application of the instruments of national power.

With all due respect to the opponents of the Powell Doctrine, free your minds. You can’t compliment Clausewitz and criticize Powell in the same breath, at least not and still maintain any level of credibility. Maybe if Alma Powell had put the finishing touches on the Powell Doctrine, we wouldn’t even be having this discussion.

No comments:

Post a Comment