PETER DÖRRIE

On the morning of Jan. 17, two suicide attackers detonated car bombs outside the United Nations base in Kidal, Mali. One bomber blew himself up at the base’s entrance—but failed to kill any peacekeepers.

About a kilometer away, another attacker detonated himself at a U.N. checkpoint, killing a Malian peacekeeper and wounding five others. Eight rockets also landed inside the base, destroying some of its structures.

About a kilometer away, another attacker detonated himself at a U.N. checkpoint, killing a Malian peacekeeper and wounding five others. Eight rockets also landed inside the base, destroying some of its structures.

It was a coordinated assault that had all the hallmarks of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb.

The January attacks boost to 44 the number of peacekeepers killed in Mali since the mission began nearly two years ago.

This makes it the bloodiest peacekeeping mission in the world.

Other U.N. missions have suffered greater total losses, sometimes due to natural disasters like the 2010 Haiti earthquake, or because civilians who work for the U.N. become targets.

But for military personnel, no mission is currently more likely to get you killed than the Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali, or MINSUMA for short.

The 9,494 soldiers and police from 40 countries in MINUSMA have the highest average yearly fatality rate for all peacekeeping missions, according to U.N. figures. At least 109 peacekeepers have sustained injuries in addition to the 44 fatalities.

The U.N. force took over from an African Union contingent in April 2013. Its goal is to stabilize Mali after the West African country underwent a 2011 coup, an almost-successful takeover by jihadi groups and a French intervention.

Chadian troops in particular bear the brunt of the risk.

Insurgents plant improvised explosive devices, detonating them in surprise attacks. Suicide bombers steer cars rigged to explode into checkpoints and base fortifications. MINUSMA’s leadership also seems to have a hard time adjusting to the tactics employed by their enemies.

Most attacks on peacekeepers in Mali are the work of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, and its affiliate groups.

And MINUSMA isn’t the only target.

There are frequent attacks on members of the Malian armed forces and French troops stationed in the country, although the death toll among the French is considerably lower, because they rarely expose their troops on a day-to-day basis—as MINUSMA has to in order fulfill its mandate.

Attacks on these allied forces have increased during the last two years, both in number and resulting casualties, pointing to a worsening security situation in Mali’s north.

The high death toll also raises questions whether the U.N. is doing enough to protect its peacekeepers from these types of asymmetric attacks, both in terms of equipment, and tactics.

The peacekeepers often ride in the open-bed pickup trucks, which are not secured in any way against IEDs or ambushes.

In 2014, the U.N. bought 16 Puma armored vehicles—which have sloped underbodies set high off the ground to protect against explosions—from South African arms firm OTT Technologies.

The deal was for private military contractor DynCorp to ship components from South Africa to OTT’s plant in Mozambique. But when the components arrived, the Mozambican government seized the components, alleging OTT violated tax and customs laws.

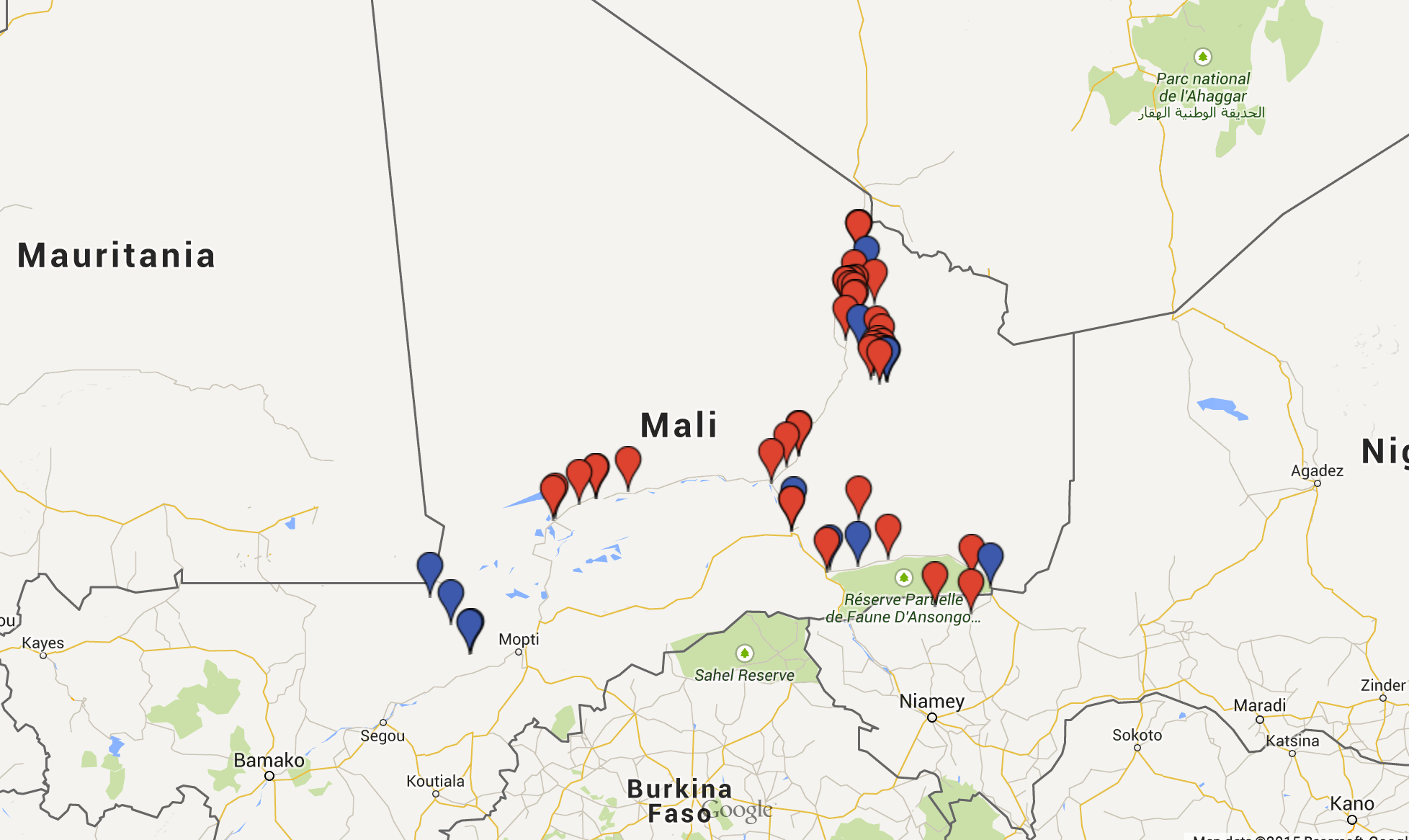

Al Qaeda-linked attacks, with those in 2014 marked in red and 2015 marked in blue. Long War Journal map

Al Qaeda-linked attacks, with those in 2014 marked in red and 2015 marked in blue. Long War Journal map

Nor are the political circumstances in Mali making the troops any safer. To be sure, peacekeepers in Mali try to act as a neutral party, but Al Qaeda very much perceives them as enemies.

The U.N. integrated the Chadian contingent relatively recently—after the experienced Chadians served as shock troops alongside the French during the January 2013 intervention to dislodge Al Qaeda from their strongholds.

Operation Serval quickly pushed Islamist forces out of the cities. But the war has since mutated, with the U.N. now facing an insurgent force that blends into the population.

At the same time, Mali’s army isn’t ready to take on the remaining militants by itself. The armed forces still haven’t recovered from their virtually complete disintegration after Mali’s civil war in 2011, despite a European training mission.

Making matters worse, the government is still embroiled in a frozen conflict with Tuareg rebels. The Tuaregs cooperate with French forces, but deny Malian troops full access to the north.

The latest round of negotiations between the Tuaregs and the government ended without any hint of a possible compromise. Which means it looks like U.N. peacekeepers will continue picking up the slack—and standing in harm’s way—for some time.

No comments:

Post a Comment