This post was provided by Steven Foster, an officer in the U.S. Army. He holds a Master of Public Policy degree from George Mason University’s School of Policy Government and International Affairs, and is currently attending the Army’s Basic Strategic Art Program. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army, the DoD, or the U.S. Government.

“No one is more professional than I…”

“…I will not only seek continually to improve my knowledge and practice of my profession…,”

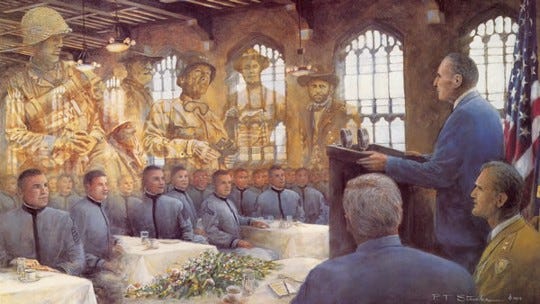

These excerpts from the NCO and Officer Creeds both highlight an important word, one that has been debated and discussed for several years. Recently on Twitter, the question was asked, “Is the military a profession?” This is not a new question by any means, but how could this question still be asked when in 1962 GEN Douglas MacArthur told the cadets at West Point, “Yours is a profession of arms”?

If you ask many senior leaders this question, particularly those familiar with the Center for the Army Profession and Ethic(CAPE), you would in most cases receive an unequivocal “yes”. For around seven years CAPE, and its predecessor the Army Center of Excellence for Professional Military Ethic (ACPME), have carried the torch for the mission of serving, “as the proponent for the Army Profession, the Army Ethic and Character Development of Army Professionals to reinforce Trust within the profession and with the American people.”[i] This brings back to light not only the original question posed above, but more importantly “If we are a profession, why do we need to be told that we are,” and, “Has this drive to build professionalism in the Army for the last seven years achieved its desired effect?”

To effectively determine if the Profession of Arms campaign has truly been successful, it is important to remember that words matter. A simple Google search of “what is a professional” will bring up myriad different articles of varying degrees of veracity. More definitions fall along the lines of, “(a person) engaged in a specified activity as one’s main paid occupation rather than as a pastime,” or, “having or showing the skill appropriate to a professional person; competent or skillful.” Simple enough. One article from the Harvard Business Review begins with a poignant caution, that it’s “easy to fall back into the ‘I’ll know it when I see it’ argument.”[ii] This is true when evaluating the professionalism of the military, especially when so many of us wear our resume on our chest (or often on the back window of our car).

Other results bring up simple tasks that are expected of even our most junior Soldiers: be on time, be reliable, be flexible, and speak up when something is wrong.[iii] Again, not a boilerplate definition of professionalism. In 1977 as the military was shifting to an all-volunteer force, Dr. Charles C. Moskos posed a similar debate in an article forParameters.[iv] In it, he examined three models of the military’s sociological construct, one of which was the professional model. Moskos cautioned that the term profession brings a specific connotation, one that brings with it the potential to segregate personnel in a way that is damaging to military cohesion.[v] Again, words matter.

Of course, we are evaluating our own professionalism, so we must hold it against or own defined standard. According to CAPE, and Army Doctrinal Reference Publication 1, a profession has five dimensions, or aspects: [vi]

Professions provide a unique and vital service to the society served, one it cannot provide itself.

Professions provide this service by applying expert knowledge and practice.

Professions earn the trust of the society because of effective and ethical application of their expertise.

Professions self-regulate; they police the practice of their members to ensure it is effective and ethical. This includes the responsibility for educating and certifying professionals.

Professions are therefore granted significant autonomy and discretion in their practice of expertise on behalf of the society.

Looking at these dimensions, the Army highlighted several areas for improvement in its CY2011 Annual Report. This report was the result of a year-long effort consisting of discussion and evaluation across the force. While the recommended initiatives resulting from that the Annual Report are still in progress, we can nonetheless see that there is work to be done, much of which we can do without the Army’s direction.[vii] Another way to look at this question beyond the contents of that report is to drive the unit of analysis down to the individual level. In the five aspects of a profession, replace “professions” with “professionals,” and ask, “Am I (are we) professional(s),” does the answer change? It shouldn’t, but it may.

Expertise is built through effective training, education, and significant self-development, an important component that is often overlooked.

The Army does provide a unique and vital service to the United States. As the proponent for the application of sustained strategic landpower in the armed forces, no one else can match this ability. To do so, the Army must lead, and be led, by experts in the application of land-based combat operations. Expertise is built through effective training, education, and significant self-development, an important component that is often overlooked. A professional should, as Machiavelli says in The Prince, “read histories and consider in them the actions of excellent men, should see how they conducted themselves in wars, should examine the causes of their victories and losses, so as to be able to avoid the latter and imitate the former.”[viii] This no doubt occurs frequently at various levels of Professional Military Education (PME), but not enough, as Major Matt Cavanaugh points out in his 2014 article in Foreign Policy, “The Decay in the Profession of Arms.”[ix] While not quite the “sky is falling” cry that came when William S. Lind lambasted the officer corps, it is a relevant call to self-reflection nonetheless.[x] There is still a disheartening lack of focus on the intellectual side of professionalism, which cripples leader development and stifles innovative thought at all levels.

This leads to self-regulation. Rather than decry the problem, Cavanaugh and others have chosen to be part of the solution.The War Council, The Bridge,The Military Leader, and theCCLKOW discussion series with King’s College London are just a few great examples of mid-grade officers working outside their day to day duties to enhance professional development opportunities for themselves and others. Moreover, the increase in the use of military blogs has led many young officers to branch into professional writing, as well as guided reading and historical discussion programs. While some have learned some difficult lessons (a certain promotable First Lieutenant comes to mind), it is nevertheless a promising sign that many of our officers see the seriousness of self-study, personal accountability for development, and policing our own. There is no reason these innovative development initiatives cannot be implemented within individual units, to enhance learning for leaders of all levels.

We see encouraging examples of professionalism in our ranks every day, but we still have work to do.

As management expert Edgar Schein says in Organizational Culture and Leadership, “cultural forces are powerful because they operate outside our awareness…Most importantly, understanding cultural forces enables us to understand ourselves better.”[xi] Looking at the Army through this lens, we must embrace the fact that as a Profession of Arms, we are all subject to the effects of the cultural dynamics in which we are operating, and all too often we need to be reminded of this fact. The expectation is that those who wear the uniform at all levels have become a part of the Profession of Arms, and likewise should exhibit the level of expertise, conduct, and stewardship commensurate with their rank, role, and responsibility. We see encouraging examples of professionalism in our ranks every day, but we still have work to do. The Army is at a key inflection point as it moves through this period of transition both in size and in its mission set. After seven years of APCME/CAPE, and nearly twice that amount of time in a long-term conflict, we must continue look for ways to advance professionalism in our ranks.

[i] “Mission & Intent | CAPE,” accessed January 8, 2015,http://cape.army.mil/mission.php.

[ii] “What Does Professionalism Look Like? — HBR,” Harvard Business Review, accessed January 8, 2015, https://hbr.org/2014/03/what-does-professionalism-look-like.

[iii] “What Does It Mean to Be Professional at Work? — US News,” US News & World Report, accessed January 8, 2015,http://money.usnews.com/money/blogs/outside-voices-careers/2013/07/22/what-does-it-mean-to-be-professional-at-work.

[iv] Charles C. Moskos, “The All-Volunteer Military: Calling, Profession, or Occupation?,” Parameters 7, no. 1 (1977): 2–9.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] “Doctrine & Policy | Center for the Army Profession and Ethic | CAPE,” accessed January 8, 2015, http://cape.army.mil/doctrine.php.

[vii] Doctrine Command, “US Army Profession Campaign,” US Army, 2012,http://oai.dtic.mil/oai/oai?verb=getRecord&metadataPrefix=html&identifier=ADA566839.

[viii] Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985).

[ix] “The Decay of the Profession of Arms,” Foreign Policy, accessed January 8, 2015, http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/01/08/the-decay-of-the-profession-of-arms/.

[x] William S. Lind, “An Officer Corps That Can’t Score,” The American Conservative, accessed January 8, 2015,http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/an-officer-corps-that-cant-score/comment-page-1/.

[xi] Edgar H. Schein, Organizational Culture and Leadership, 4th ed.., Jossey-Bass Business & Management Series ; 2 (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010).

No comments:

Post a Comment