20 Questions with Tim Kane

Talent. We’re not always sure what it is, but we know we want some. But do we truly value talent? How well do we manage it? Do we really manage talent at all?

Talent. We’re not always sure what it is, but we know we want some. But do we truly value talent? How well do we manage it? Do we really manage talent at all?

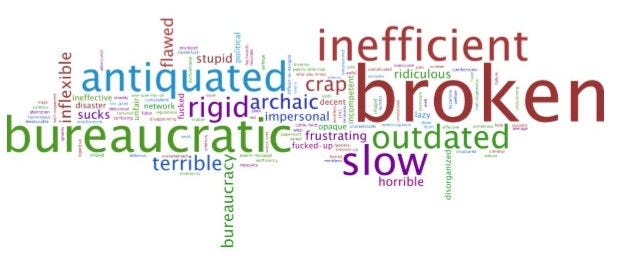

Several months ago, I sat in a very crowded conference room as some of the Army’s most senior leaders discussed talent management. Recognizing that the challenges of the 21st century don’t lend themselves well to a Cold War personnel management model, the discussion focused on how to “get over the hump.” The only system more entrenched than personnel management might be acquisitions: achieving true change in either is like eating an elephant… while the elephant is alive, growing, and putting up a fight. But the harsh truth remains. We no longer have the luxury of a uniformed military so deep that we can afford to bleed out the very talent we so desperately need to retain.

But it’s just too hard to do, right?

Then along came Tim Kane. Air Force Academy graduate, nationally-recognized economist and entrepreneur, think tank boy genius, author. His 2012 book, Bleeding Talent, served as a clarion call for reform, a throat punch to a system optimized for another time, another war. His name soon became synonymous with talent management or, more accurately, talentmis-management. In the same breath leaders would cite his work, they would curse him for the effort required to realize the potential of personnel system optimized for the here and now.

25 years after Tim Kane strolled away from the halls of the Air Force Academy, the debate on talent and talent management rages on. While the Army is finally taking steps toward institutionalizing programs that will provide some degree of professional autonomy consistent with the needs of an all-volunteer force, the policy challenges are significant across the services and the bureaucratic inertia seems like an ascent of K2 on most days.

Can it be done? Well, we’re about to find out.

1. Talent management. An impossible goal?

That’s funny, but no. Talent management is like tactical combat: it’s going to happen one way or another. The question is how well a military wants to do these things. The Pentagon is excellent at fighting, and made a choice many decades ago to continuously improve its combat tactics. The Pentagon is also managing talent, whether it realizes it or not, but does not have the same rigorous, skeptical, innovative approach to constantly revolutionizing personnel policy. It doesn’t wargame HR. It barely looks at what cutting edge technologies exist in other organizations. Unfortunately, the military branches treat personnel like a logistics problem — something Don Vandergriff calls the beer can model (consume, crumple, restock). I like to emphasize that the military services are way better at managing talent under the All-Volunteer Force than they were under the draft. At this moment, we are stuck in that central planning mentality. The irony for me is humorous: America’s cold warriors successfully defended free-market capitalism and drove central planning out of Moscow, but it escaped and infiltrated our personnel commands.

That’s funny, but no. Talent management is like tactical combat: it’s going to happen one way or another. The question is how well a military wants to do these things. The Pentagon is excellent at fighting, and made a choice many decades ago to continuously improve its combat tactics. The Pentagon is also managing talent, whether it realizes it or not, but does not have the same rigorous, skeptical, innovative approach to constantly revolutionizing personnel policy. It doesn’t wargame HR. It barely looks at what cutting edge technologies exist in other organizations. Unfortunately, the military branches treat personnel like a logistics problem — something Don Vandergriff calls the beer can model (consume, crumple, restock). I like to emphasize that the military services are way better at managing talent under the All-Volunteer Force than they were under the draft. At this moment, we are stuck in that central planning mentality. The irony for me is humorous: America’s cold warriors successfully defended free-market capitalism and drove central planning out of Moscow, but it escaped and infiltrated our personnel commands.

2. Recently, an Army career manager wrote that most officers are either too ignorant or arrogant to understand the finer points of personnel management. A fair criticism or a defense of the status quo?

I just read that essay by Lt Col Frost this evening — no kidding — and I don’t think the author is going to get very far with a message that implies soldiers aren’t patriotic or smart enough to make their own career choices. In a democracy, it seems to me that respect for volunteers should be the bedrock value, rather than the “we know better, trust us” tone.

With that said, the Frost article is an exception to the rule, which is that most everyone is hungry for HR reform. Most staffers at HRC and AFPC and Millington are great people, doing the best they can, and based on my conversations with them, they see more flaws in it than we do. Go ahead and hate the system, not the poor folks tasked with running it. I’ve been very heartened by the fact that some of the first and strongest fans of my book (Bleeding Talent) are personnel officers. The Coast Guard team was first; they had me out to brainstorm ways to move policy changes at the higher level. The most amazing experience was an Army officer who asked me to sign five copies of the book so that he could hand them out at his farewell party when he left HRC.

3. What drove your decision to leave the Air Force?

Even before I showed up for our first day at the Academy, my secret ambition was to be the first man on Saturn. No joke. I found out Saturn is like 99% freezing liquid about the same time I fell in love with economics during my sophomore year. Then the Cold War ended during my senior year. Remember how sudden that moment was? One month, you’re thinking nuclear warfare is inevitable. Next month, the great rival of the past half century just evaporates. The flawed lesson I took away was that military force would not be very relevant in the 21st century. Wrong! Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait literally weeks after I decided to go into intelligence instead of flying. The fact is that I never expected a military career, but am really proud I served for five years, and proud I was assigned overseas.

4. Why is talent management so damned hard?

It’s not! What makes talent management a fun topic for this veteran / economist is that it’s so (wait for it) easy. The people who understand this instinctively have served in uniform AND in the private sector. They have two points of reference, kind of like how having two eyes gives you depth perception. You know how sometimes it’s hard to explain things to civilians? It’s just as hard to explain the civilian labor market to active duty folks. What they don’t see is that talent management works, just like any market works, when it is not managed, per se. Gardeners don’t really grow plants. They weed and let the plants grow themselves.

5. If the Secretary of the Air Force handed you the keys to the Air Force Personnel Center tomorrow, what would be the first three things you’d change?

So easy: agency, price, and information. First, I’d give commanders the authority (and responsibility) to hire. AFPC’s job would be to facilitate, not to control, assignments and promotions. Likewise, officers and enlistees would be granted agency to control their own careers. Second, the USAF critics will say that they tried a decentralized assignments market in the 1990s and it failed. Whoa, Trigger! They tried a market with no price flexibility, thin information, and very little commander agency. To work, there has to be wage flexibility, something like automatic bonuses for unfilled jobs (e.g., 10% pay bump if a job remains unfilled for 60 days, plus extra leave, plus open to lower-ranks). Third, AFPC would allow greater information about personnel. An improved OER/OPR would be sweet, but step back and ask why it even matters. USAF performance evals are currently an embarrassment to all concerned, and they are really hard to change for lots of reasons, some cultural. Fix it by transcending it. If commanders are doing the hiring, they should and will ask for more and better evaluations of personnel — letters of recommendation, resumes, LinkedIN profiles. Those pieces of information are literally verboten today. A more flexible process will really improve the culture, and that’s what will drive OER/OPR reform.

6. We’re in the midst of another drawdown. Why does it seem like we have to learn the same lessons all over again?

Different services are wrestling with the drawdown in different ways, but the budget cuts are (1) deeply unfair to those in uniform, (2) a consequence of dysfunctional federal government more than Pentagon problems, and (3) a once-in-a-generation opportunity for personnel reform. Let’s recall military life in the 1960s and 1970s before the AVF got squared away. Morale was horrible, and deservedly so. Enforced servitude was unfair, and it wasn’t until the 1980s that a new generation of officers realized how radical an improvement the all-volunteer military was. We will never go back. The lesson this generation of flag officers needs to re-learn is philosophical: coercion hurts productivity in the long-run. Our challenge is that coercion is built into the fiber of U.S. military personnel management — coated in the mantra of service over self — but it has a very, very short horizon, putting bodies in billets by sacrificing everything else: morale, money, unit effectiveness, development, trust, flexibility, retention.

7. Are there ever days when you wish you were still wearing Air Force blue?

Wow, I don’t really think about that at all. I am jealous of my friends in uniform, because the camaraderie they have and the admiration I have for them is unparalleled, but I love doing the work I do now at Stanford’s Hoover Institution. Beside, ask my kids, I’m wearing my USAFA shirts pretty much every day (and my “Kick Army’s A**” button from the 1986 game).

8. How has “Bleeding Talent” changed your average day?

Not as much as you might think! The book was more successful than anyone expected, but I’m still waiting for Steven Spielberg to call and ask for the movie rights, or for Brad Pitt to make it happen. Let’s keep some perspective: this is a quiet battle we’re in. Most of America, most of Congress, even most veterans will not focus on personnel policy like we freaks do.

9. What’s the tipping point for talent retention? At what point do we start to “bleed out” professionally?

Too late. The Body Pentagonic has been bleeding out pretty much constantly since before we were born. It simply has the luxury of a never-ending supply of fresh, high-quality blood. The military services — all five of them — recruit beautifully. They retain okay, too, in fact. But they bleed internally (meaning that people are misallocated and wasted) to a degree that would ruin any other organization without the draw on young, idealistic patriots.

10. You’re currently writing a new book. Want to share a preview?

The working title is Leading Talent. I hope to write something relevant to the military, however, my idea is that we don’t need another tome focusing on it alone. I’m looking at how different organizations blend leadership culture and personnel practices to achieve excellence. Frankly, a lot of the management literature strikes me as jargony junk. Applying analytical rigor is tough, and I’ve hardly found the secret, but it’s fascinating.

One nugget worth sharing: I was curious how much talent matters for success. How do you even start to actually analyze that? Turns out the NCAA football teams have talent assessment down to a science with recruiting high school players. So I’m working with another economist on a study of talent as an input and quality wins as the output, and we found that intangibles account for 60% of wins and talent less than 40%. Here’s the kicker, once we account for all the individual coaches over the past decade, talent becomes irrelevant! (Of course, that’s because the best coaches attract the best talent. Still, pretty cool result).

11. What advice would you offer for a newly-commissioned officer?

Enjoy it. Enjoy the people. Enjoy the awesome equipment. Enjoy basking in the admiration of your fellow Americans. You will never feel this way again. As a practical matter in the shape of how to be successful? Show up early, work hard, be honest, help everyone.

12. The service culture has evolved significantly since your time in uniform. How can we be more successful at mentoring young leaders today?

Is this about Millennials? Depeche Mode said it best: people are people. Young leaders today are the same as young leaders in any era, and they will find mentoring naturally.

13. You’ve had the opportunity to interact with some of the greatest leaders of our generation. Who stands out as the greatest combat leader of the past decade?

Combat leader? I have no right to answer that. But the people I respect say David Petraeus and Jim Mattis. Mattis is a colleague of mine at the Hoover Institution but I was a fan of his years before. He is decisive. He is wise. And man, does he love the Marine Corps. As for me, true story: I was visiting West Point back in 2010 and it occurred to me that the plebes were waymore relaxed at noon meal formation than we were at USAFA in 1986. I was a bit irritated at first, then I had this realization that every single one of them joined with eyes wide open. I had volunteered for military service; they had volunteered for war. Respect. This generation of troops makes me humble. Seriously, I don’t feel the right to criticize the Pentagon on most days, and I wouldn’t do it if I hadn’t gotten so much support from this younger generation thanking me for some early research I did. They are hungry for reform, and I am following a tradition of free-market economists at Hoover like Milton Friedman and Martin Anderson, men who advocated so eloquently to end conscription and then to make the AVF work. I was able to attend Martin Anderson’s funeral a few days ago to pay my respects because he was the godfather of the AVF. He pushed Nixon to adopt in 1967 and fought the Pentagon to implement it in 1973. Policy Ninja.

14. Who were your greatest influencers as a young leader?

Reagan was president when I joined and he looms larger every year. But when I was a boy, I was inspired by JFK, the Apollo astronauts, Chuck Yeager. My USAFA professors (Jerry Ludke, Bob Waller, Ed Wright) turned me on to intellectual heroes including Milton Friedman, Joseph Schumpeter, and Francis Fukuyama. But to be totally honest, I was a comic book nerd growing up, big time. Whoever was writing the X-Men, Avengers, and Iron Man in the late 1970s, they’re responsible for getting me fired up about science and serving others.

15. What motivates you? What is your passion in life?

B1G Ten Football, Family, and Faith. My passion in life is to create. I’m happiest when I am building something new, whether a treehouse in the backyard or a new economic model or a board game.

16. What makes you laugh?

Good stories. 2014 was a rough year for comedians, right? My generation grew up listening to Bill Cosby and Robin Williams. Thank God we still have Steve Martin and Eddie Murphy. Stand up albums: lost art.

17. There’s a rumor that you left the Air Force because you were a mediocre crud player. Any truth to that rumor?

Partially true. My game was spades. Had an AF pal who drew all 13 spades in one hand on a TDY trip to Scotland, of all places. I switched to poker when I was stationed overseas, but military guys are too good at poker. Later, I played with a group of economists in DC and made a killing — those economists are only good with money in theory!

18. iPad, tablet, or old-fashioned book made from dead trees?

All three. I bought one of the first Kindles, but find myself reading way more on the iPhone than I would have guessed. Even so, there’s nothing like reading a dead tree during the last 20–60 minutes of the day. I’ve fallen asleep reading Tom Ricks almost as often as George RR Martin.

19. Tell me about the last good book you read?

Once I get hooked by an author, I read all of his/her works. I’ve been hooked by SF writer Neal Stephenson for a long time, and find myself re-readingAnathem during Christmas vacation. For non-fiction, Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature is a masterpiece I am halfway through.

20. What’s next for you?

I’d love to write another few books. Leading Talent is one. The Good Country is another, based on a recent cover story I wrote forCOMMENTARY. I have a book’s worth of ideas for a domestic economic policy that I’ve been discussing with Glenn Hubbard. And lastly, I have a science fiction story that would be fun to share. Time is the enemy. My New Year’s Resolution is to give up Facebook until at least one of those books is written. Or a screenplay … wait, there’s a call coming in and I think it’s Spielberg!

No comments:

Post a Comment