The sailing branch led Pentagon research into glowing chemicals

You’ve probably played games or gone hiking with a glow stick—a plastic tube filled with chemicals that give off a soft, eerie light.

But you might not know that the U.S. Navy was deeply involved in the development of the glow-in-the-dark novelty.

Only for the sailing branch, it wasn’t for fun.

By 1962, the sailing branch was investing a lot of time and effort to find so-called “chemiluminescent” compounds for military use.Chemiluminescence is the light you get as certain chemicals interact.

The year before, the DuPont chemical company had invented a new formula called PR-155. The liquid was lighter than water and produced a greenish-yellowish light when exposed to air.

After the discovery, the Naval Ordnance Test Station at China Lake in California partnered up with DuPont and kicked off the Target Illumination and Recovery Aid project, or TIARA.

The Advanced Research Projects Agency—the predecessor to the Pentagon’s current research arm DARPA—funded the program.

The “formulation can be used whenever it is desired to illuminate an area or an object at night,” according to a contemporary issue of the official Naval Weapons Bulletin.

And chemists could remix the material to produce more or less light for varying lengths of time or even to change its basic state. For example, DuPont and China Lake employees created Marsticks—“a luminous marking crayon”—by blending PR-155 with wax, according to an official Navy history.

At top, above and below—U.S. Army soldiers with glow sticks. Army photos

At top, above and below—U.S. Army soldiers with glow sticks. Army photos

Researchers at China Lake envisioned troops and sailors using the chemicals to see in the dark and point out targets for air and artillery strikes. Navy weaponeers promptly filled experimental cluster bombs, mortar shells, land mines and grenades with PR-155.

Glowing panels or sticks could also indicate friendly troop positions, mark out impromptu air strips or help choppers find downed fliers. Since the compound would float, submarines might be able to call in a supply drop from beneath the waves by popping out a PR-155-filled canisters … or signal that the vessel was in trouble.

DuPont’s liquid also offered a safer alternative to traditional flares. Unlike burning white phosphorus or magnesium, chemiluminescent reactions generally produce very little heat.

In addition to tests at China Lake, Navy personnel showed off these glowing wares to Army Special Forces and the Marine Corps. The Pentagon also sent a batch of Marsticks and TIARA grenades to South Vietnam.

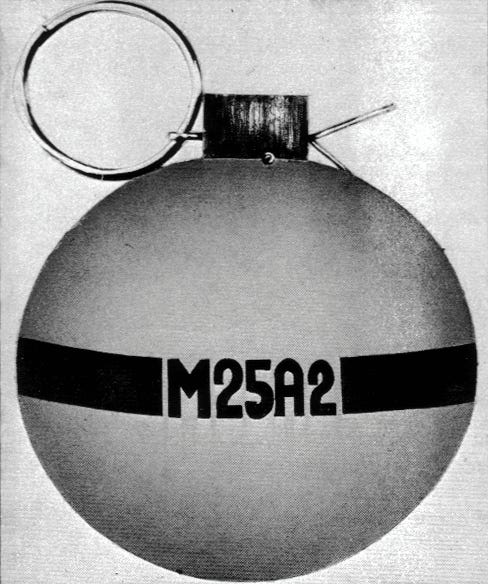

An M-25A2 tear gas grenade. U.S. Army art

The special munitions shared their basic design with the M-25 tear gas grenade. Personnel at China Lake simply filled their versions with PR-155 instead.

But the grenades repeatedly malfunctioned and the evaluation in Southeast Asia ground to halt. Only a year after the TIARA program got going, tests in Vietnam were “indefinitely suspended,” according to a periodic review of ARPA’s work in the country.

And the faulty weapons were just the beginning of TIARA’s troubles.

The Naval Medical Center had also just finished testing the effects of the supposedly non-toxic PR-155 on animals. The results indicated that the compound could actually be dangerous if someone inhaled the fumes in a confined space.

On top of that, the sailing branch determined the compound itself had caused the problems with the grenades. “It is evident that gross exposure to TIARA fumes irreversibly affects the detonators,” the report explains.

With the mounting problems, ARPA cut its support for PR-155, as well as an improved PR-156 compound. At the same time, the Pentagon scientists awarded a separate contract to the American Cyanamid Company for a compound it was developing called Cyalume.

In spite of this, the TIARA program trudged along. By the late 1960s, China Lake had delivered improved grenades and spray cans full of PR-155 to SEAL Teams in Vietnam. The elite Navy commandos used these weapons to tag guerrillas they were trying to capture.

“Anyone inside the area being searched by the SEALs would find it very hard to to hide in the dark when they glowed like a giant firefly,” historian Kevin Dockery writes in his book Special Warfare Special Weapons.

In 1966, the Pentagon also used the compound as part of biological weapons tests. During an exercise codenamed Yellow Leaf, aircraft dropped TIARA bomblets in Hawaii’s Ola’a Forest Preserve to simulate how germ-filled weapons might spread in a jungle environment.

But these specialized scenarios couldn’t save the program. The Army’s 1st Infantry Division—also in Vietnam—tried out the grenades and came away disappointed.

The soldiers reported that PR-155 mixture wasn’t bright enough to be clearly seen by aircraft and didn’t shine long enough to be useful anyways. Army officials declined to buy any of the grenades.

The Navy itself canceled a project to build rockets with TIARA warheads. The sailing branch was apparently disappointed that it would take more than a year to finish the basic design, according to an annual history.

The Pentagon clearly had lingering safety concerns too. “No further

information is available on this substance,” is all a decade-old Deployment Health Support Directorate fact sheet on the Yellow Leaf experiment has to say on the matter.

On the other hand, researchers found that Cyalume was only mildly toxic to the average person. Today, poison control centers mostly offer warnings about temporary skin and eye skin and eye irritation if you happen to break open a glow stick.

If you swallow any, these organizations recommend you rinse out your mouth, drink some water or milk and wait to see if you have a more severe reaction before seeking medical attention. The compounds can cause blisters and chemical burns if left on the skin or undiluted in the throat or stomach.

By the 1970s, the Navy had teamed up with American Cyanamid, leading to the first mass-produced glow sticks, according to a chronology of achievements at China Lake. You can still buy these Cyalume ChemLights.

Now you can find those glowing, chemical-filled tubes throughout the U.S. military—and at your local gas station or party store.

No comments:

Post a Comment