BY BRAHMA CHELLANEY

Despite booming two-way trade, strategic discord and rivalry between China and India is sharpening. At the core of their divide is Tibet, an issue that fuels territorial disputes, border tensions and water feuds.

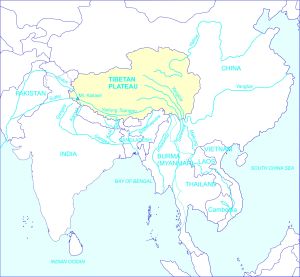

The Tibetan plateau is Asia’s “water tower.” © Brahma Chellaney, Water: Asia’s New Battleground (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2013).

Beijing says Tibet is a core issue for China. In truth, Tibet is the core issue in Beijing’s relations with countries like India, Nepal and Bhutan that traditionally did not have a common border with China. These countries became China’s neighbors after it annexed Tibet, a sprawling, high-altitude plateau where, after waves of genocide since the 1950s, ecocide now looms large.

Take China’s relations with India: Beijing itself highlights Tibet as the core issue with that country by laying claim to large chunks of Indian land on the basis of purported Tibetan ecclesial or tutelary links, rather than any professed Han Chinese connection. Indeed, since 2006, Beijing has a new name — “South Tibet” — for the northeastern Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, which is three times the size of Taiwan and twice as large as Switzerland.

Tibet historically was the buffer that separated the Chinese and Indian civilizations. Ever since Communist China, in one of its first acts, gobbled up that buffer with India, Tibet has remained the core matter with India.

In the latest reminder of this reality, President Xi Jinping brought Chinese military incursions across the Indo-Tibetan border on his India visit in September. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government responded to the border provocations by permitting Tibetan exiles to stage protests during Xi’s New Delhi stay.

In response to China’s increasing belligerence — reflected in a rising number of Chinese border incursions and Beijing’s new assertiveness on the two Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir — India since 2010 has stopped making any reference to Tibet being part of China in a joint statement with China. It has also linked any endorsement of “one China” to a reciprocal Chinese commitment to a “one India.”

Yet the Chinese side managed to bring in Tibet via the back door in the Modi-Xi joint statement, which recorded India’s appreciation of the help extended by the “local government of Tibet Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China” to Indian pilgrims visiting Tibet’s Kailash-Mansarover, a mountain-and-lake duo sacred to four faiths: Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Tibet’s indigenous religion, Bon. Several major rivers, including the Indus and the Brahmaputra, originate around this holy place.

Actually, a succession of Indian prime ministers has blundered on Tibet. Jawaharlal Nehru in 1954 ceded India’s British-inherited extraterritorial rights in Tibet and implicitly accepted the plateau’s annexation by China without any quid pro quo. Under the terms of the 1954 accord, India withdrew its “military escorts” from Tibet and handed over to China the postal, telegraph and telephone services it operated there.

But in 2003, Atal Bihari Vajpayee went further than any predecessor and formally surrendered India’s Tibet card. In a statement he signed with the Chinese premier, Vajpayee used the legal term “recognize” to accept what China deceptively calls the Tibet Autonomous Region as “part of the territory of the People’s Republic of China.”

Vajpayee’s blunder opened the way for China to claim Arunachal Pradesh as “South Tibet,” a term it coined to legitimize its attempt at rolling annexation. In fact, since 2010, Beijing has also questioned India’s sovereignty over the state of Jammu and Kashmir, one-fifth of which is under Chinese occupation and another one-third under Pakistani control.

During Xi’s visit, it was by agreeing to open a circuitous alternative route for pilgrims via the Himalayan Indian state of Sikkim that Beijing extracted the appreciation from India to China’s Tibet government. Given that the sacred Kailash-Mansarovar site is located toward the western side of the Tibet-India border, the new route entails a long, arduous detour — pilgrims must first cross eastern Himalayas and then head toward western Himalayas through a frigid, high-altitude terrain.

One obvious reason China chose the roundabout route via Sikkim is that the only section of the Indo-Tibetan border it does not dispute is the Sikkim-Tibet frontier. Beijing recognizes the 1890 Anglo-Sikkim Convention, which demarcated the 206-km Sikkim-Tibet frontier, yet it paradoxically rejects as a colonial relic Tibet’s 1914 McMahon Line with India, though not with Myanmar.

The more important reason is that China is seeking to advance its strategic interests in the Sikkim-Bhutan-Tibet tri-junction, which overlooks the narrow neck of land that connects India’s northeast with the rest of the country. Should the “chicken’s neck” ever be blocked, the northeast would be cut off from the Indian mainland. In the event of a war, China could seek to do just that.

Two developments underscore China’s strategic designs. Beijing is offering Bhutan a territorial settlement in which it would cede most of its other claims in return for being given the strategic area that directly overlooks India’s chokepoint. At the same time, Beijing is working to insidiously build influence in Sikkim, including by shaping a Sino-friendly Kagyu sect of Tibetan Buddhism.

This sect controls important Indian monasteries along the Tibetan border and is headed by the China-anointed but now India-based Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley. The Indian government has barred Ogyen Trinley — who raised suspicion in 1999 by escaping from Tibet with astonishing ease — from visiting the sect’s headquarters in Sikkim. Indian police in 2011 seized large sums of Chinese currency from his office.

India, however, has permitted the Mandarin-speaking Ogyen Trinley to receive envoys sent by Beijing. In recent years, he has met Han Buddhist figures as well as Xiao Wunan, the effective head of the Asia-Pacific Exchange and Cooperation Foundation. This dubious foundation, created to project China’s soft power, has unveiled plans with questionable motives to invest $3 billion at Lord Buddha’s birthplace in Nepal — Lumbini, located just 22 km from the open border with India.

Since coming up to power six months ago, Modi has pursued a nimble foreign policy. One key challenge he faces is how to build leverage against China, which largely sets the bilateral agenda, yet savors a galloping, $36-plus billion trade surplus with India.

Moreover, past Indian blunders on Tibet have helped narrow the focus of Himalayan disputes to what China claims. The spotlight now is on China’s Tibet-linked claim to Arunachal, rather than on Tibet’s status itself.

To correct that, Modi must find ways to add elasticity and nuance to India’s Tibet stance.

One way for India to gradually reclaim its leverage over the Tibet issue is to start emphasizing that its acceptance of China’s claim over Tibet hinged on a grant of genuine autonomy to that region. But instead of granting autonomy, China has make Tibet autonomous in name only, bringing the region under its tight political control and unleashing increasing repression.

India must not shy away from urging China to begin a process of reconciliation and healing in Tibet in its own interest and in the interest of stable Sino-Indian relations. China’s dam-building frenzy is another reminder that Tibet is at the heart of the India-China divide.

That a settlement of the Tibet issue is imperative for regional stability and for improved Sino-Indian relations should become India’s consistent diplomatic refrain. India must also call on Beijing to help build harmonious bilateral relations by renouncing its claims to Indian-administered territories.

Through such calls, and by using expressions like the “Indo-Tibetan border” and by identifying the plateau to the north of its Himalayas as Tibet (not China) in its official maps, India can subtly reopen Tibet as an outstanding issue, without having to formally renounce any of its previously stated positions.

Tibet ceased to be a political buffer when China occupied it in 1950-51. But Tibet can still turn into a political bridge between China and India. For that to happen, China must start a process of political reconciliation in Tibet, repudiate claims to Indian territories on the basis of their alleged Tibetan links, and turn water into a source of cooperation, not conflict.

Brahma Chellaney, a regular contributor to The Japan Times, is the author of “Water, Peace, and War” (Rowman & Littlefield).

No comments:

Post a Comment