The Air Force’s top secret mines didn’t work very well

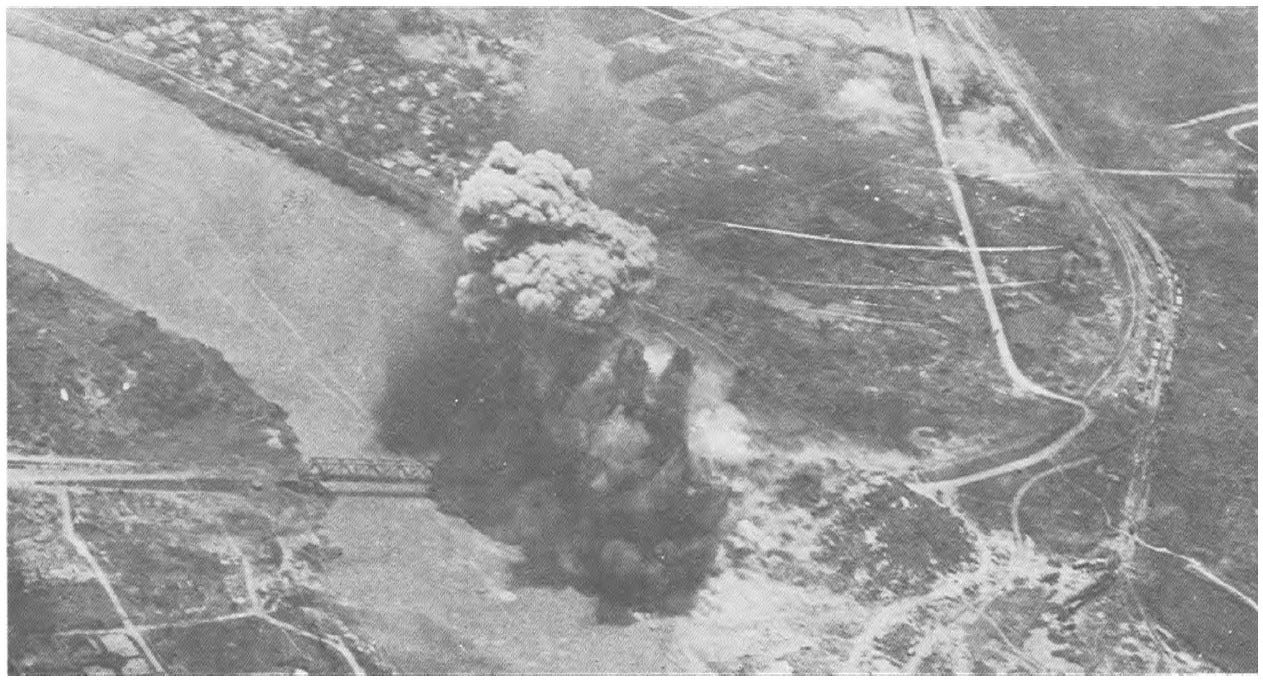

In 1965, the U.S. Air Force set out to destroy the Thanh Hoa bridge in North Vietnam. The crossing over the Song Ma River was a major artery for troops and supplies heading south.

But the span—nicknamed Hàm Rồng, meaning “dragon’s jaw” in Vietnamese—was heavily defended and seemingly impervious to American ordnance.

And despite sucking up Hanoi’s time and resources, the bridge quickly became a symbol of defiance and determination in the face of a much larger and more powerful enemy.

So by September, the Air Force’s Armament Laboratory had started work on a unique floating bomb it hoped would finally blast the structure for good. The top secret project—Operation Carolina Moon—involved some of the most advanced technology available at the time.

The flying branch was frustrated with the ineffectiveness of previous attacks. During one early strike, F-105 Thunderchief fighter-bombers and other aircraft hit the structure more than 300 times without inflicting any lasting damage.

“The hard fact was that 750-pound bombs just were not big enough to

deliver the coup de grace to such a formidable structure,” an official Air Force history explains.

So even when American munitions—including early guided missiles and bombs—did damage the span, North Vietnamese repair crews quickly put it back into business.

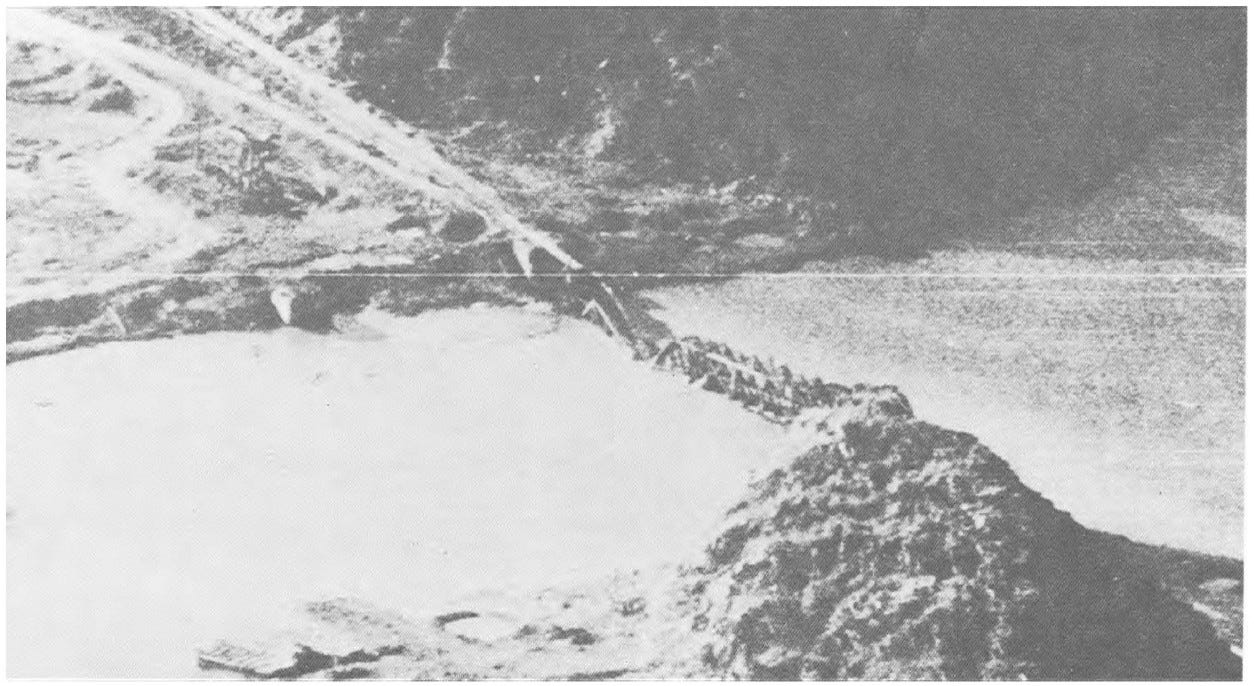

At left—the Thanh Hoa bridge survives an early attack. At right—the Dragon’s Jaw is finally destroyed in 1972. At top—a U.S. Air Force C-130 in Vietnam. Air Force photos

At left—the Thanh Hoa bridge survives an early attack. At right—the Dragon’s Jaw is finally destroyed in 1972. At top—a U.S. Air Force C-130 in Vietnam. Air Force photos

The Air Force needed a weapon that was large enough to actually bring down the Dragon’s Jaw—and keep it out of service permanently. The weapon also had to be accurate enough to hit the bridge as pilots dodged murderous anti-aircraft fire.

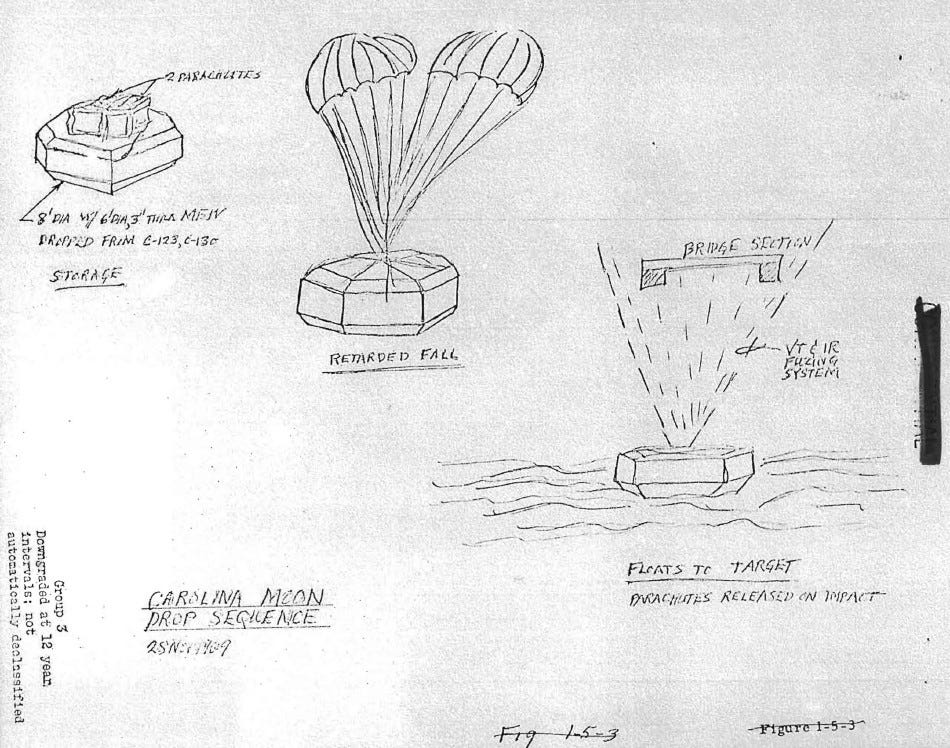

The Carolina Moon plan called for lumbering C-130 cargo planes to drop the massive bombs by parachute into the Song Ma. The mines would then float downriver to the Dragon’s Jaw. The method allow the attacking aircraft to avoid some of Hanoi’s air defenses. The ordnance itself did half the work.

The new weapons each weighed nearly 4,000 pounds and were eight feet wide and three feet tall, according to reports we obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request. These documents do not describe how the designers managed to keep the weapon buoyant.

The mines’ steel casings were so large that the flying branch turned to the Atomic Energy Commission for help.

The Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge, Tennessee built the bodies using machinery originally intended for making nuclear weapon parts.

Unfortunately, we did not receive any additional records from subsequent FOIA requests to the Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the Y-12 Complex.

Inside the metal shell, the bombs had a 500-pound warhead that would explode upward from underneath the bridge. Air Force weaponeers estimated the weapon would produce a blast equivalent to one kiloton of TNT.

F-4E Phantoms and F-105G Thunderchiefs refuel after a mission over North Vietnam. Air Force photo

F-4E Phantoms and F-105G Thunderchiefs refuel after a mission over North Vietnam. Air Force photo

There were two different fuzes to set off the mines once they were in position. The primary sensor was a radar-activated detonator the engineers borrowed from the CIM-10 Bomarc surface-to-air missile.

The Bomarc was the only SAM the Air Force ever operated. At the time, the flying branch was in the process of scrapping the missiles and their launch sites.

The fuze from the CIM-10 would go off if it detected a large mass overhead—a bridge, for instance. The designers modified the system to make sure it could differentiate between a big structure and smaller objects like “low-flying aircraft or birds,” the reports say.

The bombs each also had an infrared sensor in case the other device failed. This optical unit was similar to the ones you see today on automated toilets.

The Air Force built 20 fully-functional mines and another 10 practice mines without any explosives. The weapons cost a total of $600,000 to make—equal to $4.5 million in today’s dollars.

Before sending the unique ordnance to Vietnam, specially trained crews tested the devices at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. But the facility had no suitable areas to run through the whole attack plan.

Instead, aircraft dropped the bombs into the water to see if they would land and float as expected. Personnel then retrieved the devices and blew them up on land under fake structures they modeled after parts of the Thanh Hoa bridge.

Apparently hand drawn illustrations of how the Carolina Moon “mine” was supposed to function. Air Force art

Apparently hand drawn illustrations of how the Carolina Moon “mine” was supposed to function. Air Force art

Less than a year after work started, American commanders had approved the operation and the floating bombs were on their way to Vietnam. However, not everyone involved was thrilled with the idea.

The Tactical Air Warfare Center worried the mines would get stuck in the river bank before getting to the Dragon’s Jaw and “concluded that the chances of success were small,” according to an official summary.

“Alternative proposals apparently offered a lesser chance of success,” the same report adds, without giving any details of these rejected plans.

At the end of May 1966, a C-130 dropped five of the bombs into the Song Ma, as planned. The pilot reported the mines successful landed in the river, but reconnaissance photos didn’t show any damage to the span from the attack.

The next day, American officials ordered another attack and told the crew to release the remaining bombs closer to the bridge. But getting closer to the Dragon’s Jaw also meant getting closer to the anti-aircraft guns and missiles.

The North Vietnamese shot down the C-130. The fate of the weapons was unclear. A flight of F-4 Phantom fighters reported seeing a bright flash in the vicinity of the Thanh Hoa bridge. The mines might have exploded when the plane hit the ground.

Through the interrogation of a North Vietnamese sailor well after the attacks, the Air Force learned that four of the bombs actually hit their mark in the second strike—but didn’t cause any significant damage to the structure.

But by that time, the flying branch had become fully invested in laser-guided munitions. Six years after the Carolina Moon missions, American pilots finally destroyed the Dragon’s Jaw with a pair of first-generation Paveway bombs.

No comments:

Post a Comment