In 1988, Soviet and American inspectors swapped places

It may seem hard to believe today, with tensions rising between Russia and the West. But late in the Cold War, both the U.S. and the USSR directly measured nuclear experiments at each others’ test sites.

The unlikely but successful collaboration helped to end the five-decade conflict.

For many years, Nick Aquilina managed contractor integration at the Nevada Test Site. “I spent my career focused on conducting safe nuclear tests, and always thought about worst-case scenarios,” he said. “We knew the names of everyone downwind.”

His most memorable work involved the Joint Verification Experiment in 1988. That year, the NTS’s manpower peaked at more than 12,000 employees and contractors. The Soviet scientists and engineers who came to monitor an American test spiced up the mix of people Aquilina oversaw.

At right—Nick Aquilina in 2014. Photo via Pahrump Valley Times. At top—the U.S. Upshot nuclear test in 1953. Photo via Wikipedia

Aquilina began his nuke career in 1962 during the most intensive period of nuclear testing. When the USSR unilaterally broke a four-year moratorium, the U.S. responded in kind. Following the near-apocalypse of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1963, America, the Soviet Union and Great Britain signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty.

The PTBT forbids nuclear testing above ground, underwater and in space. France and China continued atmospheric and undersea tests for another 20 years before finally joining the treaty. U.S. and Soviet tests went underground—and stayed there until the end of nuclear testing in the early 1990s.

The first strategic-arms treaties in the early 1970s ran into Congressional opposition over verification. The Threshold Test Ban Treaty limited nuclear tests to yields of just 150 kilotons. Hawkish legislators wanted proof of what the Soviets were doing down there.

The first strategic-arms treaties in the early 1970s ran into Congressional opposition over verification. The Threshold Test Ban Treaty limited nuclear tests to yields of just 150 kilotons. Hawkish legislators wanted proof of what the Soviets were doing down there.

Signed in 1974, the TTBT wasn’t ratified by the U.S. Senate until 1991. Even if American scientists could detect large underground explosions, critics pointed out, how could we be sure the Soviets weren’t exploding bigger bombs than they were allowed to?

Despite its suspicions, the U.S. abided by the terms of the treaty until its ratification.

In January 1988, Assistant Secretary of Defense Troy Wade called Aquilina to tell him that the Russians were coming. “A delegation will visit the NTS to get familiar with the place, because we’re going to conduct joint nuclear tests with them,” Aquilina recalled Wade saying.

The Joint Verification Experiment would prove to Congress that America could verify Soviet compliance with the TTBT.

Paul Robinson, the U.S. arms-control ambassador in Geneva, sent Aquilina the protocols for the JVE that Robinson and his Soviet counterparts had worked out. Just 45 people at a time would be allowed to visit each nation’s test sites, and the verification measures had to be non-intrusive. That is, no American instruments could be bolted onto a Soviet test device and vice versa.

Testing must be done without touching, so to speak.

The protocols gave Aquilina a lot to juggle. Workers from many different military contractors had to work on the verification systems, including scientists, weaponeers, drillers, riggers and inspectors. Getting everyone into the USSR in 45-person groups, each with the right mix of skills, took some effort.

The non-intrusive instrumentation the U.S. employed involved drilling. Officials placed an instrument package designed by Lawrence-Livermore Laboratory—called CORRTEX—in a 100-foot-deep shaft adjacent to the Soviet test shaft. The Americans had to bring their own drilling rig.

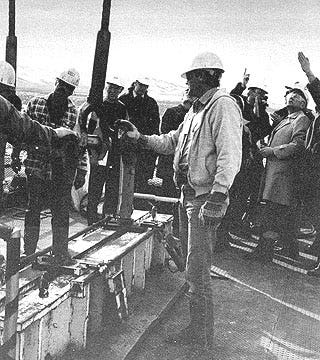

Soviet inspectors observe American drilling operations at NTS. Photo courtesy of National Nuclear Security Administration/Nevada Field Office

Soviet inspectors observe American drilling operations at NTS. Photo courtesy of National Nuclear Security Administration/Nevada Field Office

Because they lacked the highly-advanced equipment the Americans took for granted, the Soviets drilled their test shafts as the rock permitted—and they were never straight.

As a result “their test rigs were much shorter and stubbier than our long tower-like rigs,” Aquilina recalled. “We could sink 96-inch shafts down 4,000 feet. Our rigs required straight, perfectly-plumb shafts.”

An Air Force C-5 Galaxy transport hauled a massive drilling rig from Nevada to Kazakhstan for the experiment along with two identical instrument trailers. Only one trailer was necessary but the Soviets insisted on choosing one of the two at random, presumably to prevent tampering.

The trailer connected to the instrument package in its own shaft near the Soviet test shaft. When the bomb exploded, the shock would crush components within the package, which measured the bomb’s yield.

Aquilina’s Soviet counterpart Gen. Arkady Ilyenko had been the test director for the gigantic Tsar Bomba test in 1961 and now ran the Soviet test site, a four-hour journey from Semipalatinsk. Russian bureaucracy sometimes drove Nick to distraction, but the Americans’ hosts in Kazakhstan made their guests feel welcome.

“The lady who cooked for our team was a good cook, but Russian food didn’t always agree with them,” Aquilina said. “One guy had a sensitive tummy and the cook added garlic to everything. We sent over fresh vegetables to vary their diet and the lady cooked the lettuce like cabbage. She was a wonderful baker, though.”

The Americans also got two beers a day. The Mormon members gave away their beers to their colleagues.

A Soviet inspector examines an American cruise missile in 1988. Photo via Wikipedia

A Soviet inspector examines an American cruise missile in 1988. Photo via Wikipedia

The Russians are coming

The first Soviet team to visit the U.S. arrived quietly at a contractor’s airfield near McCarran International Airport. Their hosts put them up at the Golden Nugget casino.

Las Vegas’ blasting capitalism must have been quite an eye-opener for the Soviets. Shopping was a popular diversion.

Ernest Williams and Frances Gwynn entertained their Soviet guests with trips to nearby Mt. Charleston, the California coast, Disneyland and softball games. The California beaches delighted the Russians.

The visitors also enjoyed their meals. “NTS was internationally famous for its chow,” Aquilina said. “We knew how important for morale it was to eat well in remote places. The steakhouse in Mercury, Nevada served great food and drink.”

Test Director Joe Behne not only impressed the Soviets. The rival Los Alamos and Livermore weapons labs also both liked him—a real rarity.

Joe had a lot to do, but the collaborative environment at NTS smoothed the way. “The morning of the test, a fed official in the shot bunker looked around and asked, ‘Who are all these people?’” Aquilina recalled.

“We had folks from 18 different organizations there and they all reported to Jim Macgruder, the test controller. It was just like NASA Mission Control, where the flight director runs the show.”

On Aug. 7, 1988, Shot Kearsarge detonated beneath the Nevada desert under the watchful eyes of the test crew and the Soviet inspection team. A month later on Sept. 14, the Americans monitored Shot Shagan in Kazakhstan, accompanied by Soviet dignitaries.

Both sides pronounced themselves satisfied with the 150-kiloton tests and their verification programs.

The collaborative spirit of the JVE endured. Nick believes that successful nuclear verification helped end the Cold War by building trust between the two sides. The Americans and Soviets developed lasting personal relationships, some of which continue to this day.

“We had reunions on the 10th and 25th anniversaries of the JVE and it was good to catch up,” Aquilina said.

As relations with Russia sour and America’s nuclear arsenal ages, we need to restore this collaborative spirit. The Bomb reminds us, in the most forceful way, that we’re all in this together.

No comments:

Post a Comment