Former ‘Call of Duty’ creative director Dave Anthony wants to change the way America thinks about conflict

Video games are huge business. For years now, digital games have earned more than the music and film industries combined. And of all of the billion-dollar properties in the industry, Call of Duty is one of the biggest.

For eight years, Dave Anthony steered the franchise. He wrote and directed five of the series’ 11 titles, helping to transform a World War II shooter into a cultural touchstone and annual entertainment event for millions of people.

After producing some of the most successful video games of all time, Anthony left the industry. A year later, the Atlantic Council—a Washington, D.C. think tank—hired Anthony to help predict the future of warfare.

Now the man who imagined video-game wars helps an influential think tanks talk about real war. At least, the ways real war might evolve.

His reception has been … chilly. Frankly, a lot of people find Anthony’s ideas pretty repulsive.

In any event, Anthony still has a hard time processing how he got from there to here. “It still boggles my mind,” Anthony tells War Is Boring. “I grew up in a really poor sort-of suburban Liverpool.”

Liverpool is the industrial city in England that’s most famous for being the birthplace of the Beatles. Anthony didn’t care for it. “ I don’t know if you know much about Liverpool,” he says, “but it’s not the greatest place to live. Not great weather. There’s lots of poverty.”

Money was always a concern for Anthony growing up. He finished college broke. “I got into the games industry out of necessity,” he says. “All I could really do was play games, so I got a job as a games tester.”

That was 20 years ago. The companies were smaller then, not the thousand-person affairs they are today. Anthony endeared himself to the heads of the studio he worked for.

“I got to know them and I offered to write on a game for free,” he says. “They accepted.”

He loved the work and did such a good job that his bosses paid him for the writing work he offered to do gratuit. “I worked on a bunch of different stuff,” he adds. “I worked on a Star Trek game. I worked on an X-Men game, but Call of Duty was when things really started to get interesting.”

The battle of Stalingrad in the very first Call of Duty. Activision capture

The battle of Stalingrad in the very first Call of Duty. Activision capture

This was in 2005, when Call of Duty—a product of California-based Activision—was still in its infancy. The World War II game surprised critics and fans with its initial release. It was different than the sci-fi shooters that dominated the market at the time. Call of Duty had more personality.

But it was only available for PC, even though at the time the real money was in the console market. Playstations and Xboxes generated millions in revenue, and Call of Duty wasn’t on them. Activision wanted to changed that.

“They were having some trouble with it and they asked if I could help them out,” Anthony tells War Is Boring. He was still in Liverpool at the time—which, more than anything else, influenced his decision to work on the game.

“I kind of had this secret desire to live in California for a long time,” Anthony admits. “California, to me, was just amazing.” As for the game he’d soon make a household name, Anthony had no idea what it was.

“It was just a name,” he explains. “I’d been working in the video game industry my whole life and I’d never heard of it.”

Under the Anthony’s direction, the historical shooter moved into the modern era. He wrote and directed five of the games. All were smash hits.

“Call of Duty: Black Ops—which I did in 2010—I believe is still the most successful game of all time,” he explains. “It’s generated almost two billion [dollars] in revenue.”

He’s not quite right. Games such as Minecraft, Grand Theft Auto V and World of Warcraft have all out-performed Black Ops … but not by much.

The secret to that success, Anthony says, is Activision’s smart approach to the market and the hard work of the teams he managed.

“People don’t realize that the size of the team you need to make these games is phenomenal,” he explains. “Black Ops 2 was 300 people internally that I managed for two years. And we had, maybe, 400 or 500 external contractors.”

After nearly a decade, Anthony was tired. “It was a great honor and privilege,” he says. “But at the end of the day, it’s a phenomenal commitment.”

The hours are grueling. Games like Call of Duty often require developers to work 16 hour days, seven days a week, for months. Anthony was recently married. He has kids, now. He felt he couldn’t fully commit to Call of Duty and his family.

And he wasn’t broke anymore. “I’ve been very fortunate to make a lot of money doing what I’ve done, but I just didn’t need to do it anymore.”

A scene from Call of Duty 2: The Big Red One, the first installment Anthony worked on. Activision capture

A scene from Call of Duty 2: The Big Red One, the first installment Anthony worked on. Activision capture

So a little over a year ago, Anthony quit. Then in September, Steven Grundman, a fellow at the Atlantic Council, called with an invitation.

“It came completely out of the blue,” Anthony recalls.

“[Grundman] said he’d been watching his son play Black Ops 2. He was amazed. He said he was impressed by how authentic it was and more specifically the geopolitical aspect of Black Ops 2—how specific it was.”

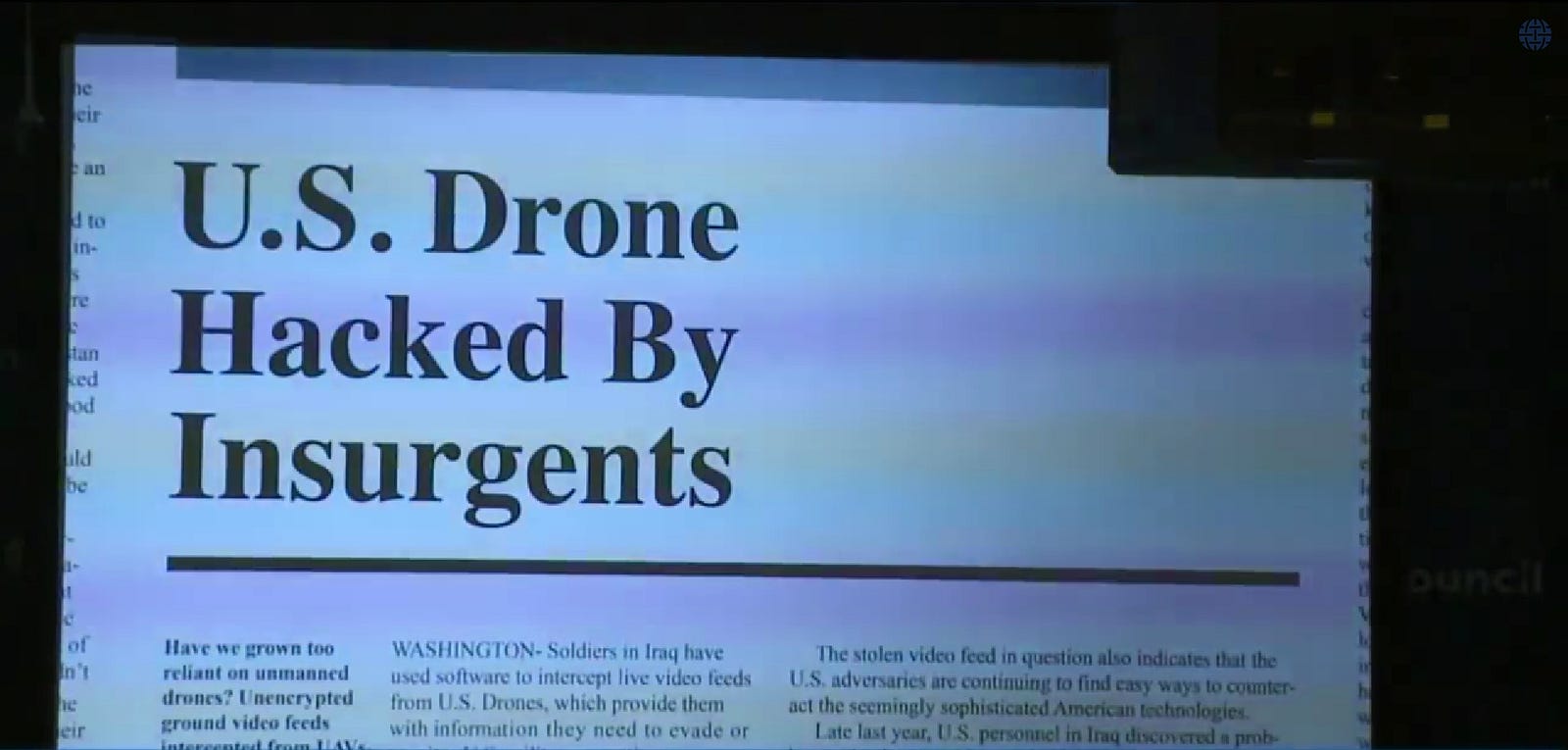

Call of Duty: Black Ops 2 is set in the 1980s and also 40 years later. The dual narrative follows the rise of a Latin American terrorist organization during the Cold War. In 2025, after years of harboring a grudge against the West, the terror group lures the U.S. into a conflict with China by hacking American drones and launching a cyber sneak attack on the Chinese stock exchange.

It’s easy to see why Grundman and the Atlantic Council were interested in Anthony.

“[The game] involved a long of things the Council had been looking at,” Anthony says. “A lot of their fears. [Grundman] wanted to know how I came up with the story. How was it that it was so close to what they think might actually happen.”

Manuel Noriega in Black Ops 2. Activision capture

Manuel Noriega in Black Ops 2. Activision capture

Grundman invited Anthony to speak as part of a panel in D.C. After that, he offered Anthony a fellowship. He accepted. “It’s unpaid work,” Anthony says. “I thought it would be a really cool opportunity to give something back to the country that’s treated me so well.”

Anthony hosted the first Atlantic Council panel of his own—“The Future of Unknown Conflict”—on Oct. 1. He spoke for half an hour about disruptive technologies and challenged Washington to change the way it thinks about modern conflict.

Anthony was not well-received. Critics took to Twitter to chastise the game director. Blogs pointed out the creepy implications of his ideas about proactive defense.

But Anthony wasn’t fazed. He knew that Beltway types would be loathe to listen to “a video-game guy.”

“When you’re working on something like Call of Duty, you’re at the top of your field,” he admits. “Everybody wants to bring you down.”

The criticism of his talk didn’t bother him. He’s heard far worse from gamers.

“The best way we come up with creative fiction is by having no fear of how things will be perceived,” he explains. “That’s the way I approached Call of Duty. It’s the way I approached the Atlantic Council. It’s the way I approach everything.”

Anthony’s hope is that people will openly discuss his ideas—no matter how wild they may seem at first. He says fear and media spin are the main obstacles to the free exchange of ideas.

“All [the media and politicians] are looking for is sensationalism,” he says. “You can see that with the Ebola thing right now. Yes, we have to be cautious, but the way it’s presented is fear-based. It’s extremely frustrating.”

“Everything in the media is 90-percent fear-based,” he continues. “The government needs to find a better way to communicate with people, to try and educate people to the nature of threats and even consider ways in which people can help overcome those threats.”

Anthony at his October talk. Atlantic Council capture via YouTube

Anthony at his October talk. Atlantic Council capture via YouTube

I ask Anthony which he fears more—domestic terrorists or foreign-born extremists.

“The specific motivation behind what they do is irrelevant,” he answers. “The problem itself is the same.”

“Technology is changing so quickly,” he adds. “How do you guard against the fact that you might have a lone wolf somewhere who will take it into his head to do something?”

Anthony is far more scared of specific technologies than specific ideologies.

“I’m terrified of drones,” he explains. “The smaller drones. My kids got a $25 drone. He flies it around the house. Can’t you just imagine someone putting a bomb on this thing?”

Anthony’s fear of new technology isn’t completely unfounded, but his disregard for the user’s motivation feels flippant.

Another of his suggestions—he mentioned it in his panel talk and brings it up again during our conversation—is downright upsetting. He recommends that public schools hire what he calls “school marshals.”

The marshals, Anthony explains, would be plain clothes military personnel whose job it would be to guard America’s public schools. This was one of the concepts Anthony’s Twitter critics found most offensive. I tell him I also find the idea a bit unsettling.

“How would you feel about it,” he says, “if yesterday there’d been an attack in a school and 300 children had been beheaded?”

I tell him in that case I might be more open to the idea, but I’d still find the whole plan a bit inappropriate.

“It’s an emotional reaction,” he says. “If this actually did happen, then you could bet that something like [school marshals] would be put in place.”

Special police forces prepare after reports of a suspected gunman at a high school in Cologne, Germany, on Oct. 20, 2014. AP photo/Frank Augstein

Special police forces prepare after reports of a suspected gunman at a high school in Cologne, Germany, on Oct. 20, 2014. AP photo/Frank Augstein

“When you’re faced with a disaster that happens,” he explains. “It forces you to put the emotional reaction aside and actually think, ‘Oh my God, we really need to fix this.’’’

For Anthony, national security threats are all about proactive solutions. Too often, he says, governments are reactionary.

“If you can think of these types of threats with a mindset of, ‘This has already happened,’ rather than, ‘This is just some idea that this might happen in the future,’ it really forces you to think about it in a different way.”

I think about this for a moment before telling Anthony that I find the whole concept of proactive defense frightening. “You get an emotional reaction,” he replies. “You get a fear reaction. And it does make you feel uncomfortable.”

Now, Anthony relies on the same fear-based tactics he derides news media and governmental officials for also using. During his Atlantic Council presentation, he told the crowd he wanted to show them what he imagined a terror attack in Las Vegas might look like.

He then played footage of a casino heist from the 2001 Kevin Costner movie 3,000 Miles to Graceland.

He ended his speech with a montage of footage depicting his own greatest fears. Isn’t Anthony guilty of the same fear-mongering and sensationalism he insists is a problem?

Images from the end of Anthony’s presentation. Atlantic Council capture via YouTube

Images from the end of Anthony’s presentation. Atlantic Council capture via YouTube

“I think before it happens it’s rooted out of fear,” he concedes. “I think afterit happens it goes from fear to prudence. Putting air marshals on planes—for example—was a very good idea.”

America didn’t deploy a lot of air marshals until after 9/11. “We’re only looking at reactionary solutions,” he says.

Again, Anthony scares me. The world he envisions is awfully similar to the one Philip K. Dick describes in his novel Minority Report—a police force arresting citizens before they have a chance to commit a crime. A dystopia of preemptive strikes. I tell Anthony this.

He concedes that there needs to be balance. The “pre-crime” profiling practice “can be extremely dangerous,” he admits.

“There’s a very fine line between how far you go before you violate people’s freedom. But what I don’t believe is happening right now, is that there’s not enough debate about where that line is.”

“For similar reasons to how you reacted to school marshals,” he continues. “You said it made you uncomfortable. I think that’s true of a lot of people. I’ve seen that reaction. And that feeling prevents the discussion.”

The world of Black Ops 2 is Anthony’s worst fears realized. Activision capture

The world of Black Ops 2 is Anthony’s worst fears realized. Activision capture

“When you’re working on creative projects, it is the discussion itself that airs out the fresh idea,” Anthony says. “Most of the time, it’s not the original idea that was suggested.”

“So in this case, I suggest the school marshals,” he points out. “School marshals won’t be what we end up with.”

“But it’s the discussion you have as a result of that suggestion that sparks the better idea,” he adds. “I would love to see that kind of thinking happen in Washington.”

“One of the biggest fears people have is public criticism,” Anthony says. He claims he just wants Americans to have a productive conversation about national security, the dangers of technology and the future of war—even if the talk frightens some people.

Anthony and I speak for close to an hour. Finally, his son pulls the phone from his hand. I hear a scuffle and laughter. Anthony apologizes. We wrap up the conversation and the man who walked away from a wildly successful career hangs up in order to enjoy an evening with the family he left it for.

I disagree with Anthony on a lot of things. Some of his ideas are a little crazy, a little hypocritical—but I’m glad he brought them up.

He’s right about one thing. D.C. needs an injection of creativity and courageous talk. More policymakers, politicians and pundits—to say nothing of members of the general public—need to have honest conversations about the stuff that scares them most.

I’m happy to be part of the conversation Anthony started.

No comments:

Post a Comment