Operating Concept

What’s in a Name?

This post is another in the #Operating: A Personal Reflection on the Army Operating Concept series and was provided by Dave “Sugar” Lyle, an U.S. Air Force strategist. The views expressed belong to the author alone and do not represent the U.S. Air Force or the Department of Defense.

When critiquing high level conceptual documents like the US Army Operating Concept, it’s important to remember what they are and what they are not. They are an attempt to steer already ongoing group conversations into specific directions that the leadership feels are needed to prepare the group for future success. They seek to reinforce or clarify some ideas, discount or refute others, and, most importantly, provide direction on how the organization will address both new challenges and existing unresolved problems. They seek to provide common starting points for the discussion and set the parameters for future debate and exploration.

They are not designed to deal with specific problems, they do not prescribe solutions, nor do they usually make specific predictions about the future, except within ranges of possibilities.

Given that perspective, and with the assumption that others more qualified than I will likely provide analysis on the “nuts and bolts” of the document, I’d like to comment on two of the specific words that the authors very deliberately chose for the most important part of the document, and why I’m glad that they did.

The words? “Complex” and “Win”, both in the title.

Complex

There is a good reason this word keeps showing up in our strategic documents like the 2010 and 2014 QDRs (which this document reflects), and there is also a reason the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff has used it consistently in his messaging. It’s a recognition that the world is becoming rapidly connected, and also that the ways we collectively make sense of the world — and define what is meant by expertise and authority — are not keeping pace with this rate of change. Some have already said “It’s just jargon — the world has always been complex.” There is an element of truth in this statement, since the experience of complexity – and complicatedness as well, for that matter – is in part an experience between ourselves and the things we observe, and remains universal across time. We experience complexity when our mental schemas — built through combinations of personal experience and theories passed on from others — are not adequate to understand and make sense of the system changes and interactions we’re observing. Over time, with knowledge and experience, we can often overcome this feeling through deduction or instruction.

But here is where “complicated” and “complex” differ: with complicated systems – such as in the case the oft-mentioned Swiss Watch – once you figure them out, your understanding of their workings will remain valid over time, and the experience of confusion and uncertainty will disappear. In contrast, complex systems are in a continuous process of co-adaptation, with ever increasing numbers of nodes and degrees of interconnection that stymie prediction and understanding. This means that you can never stop and rest on your cognitive laurels, assuming your understandings from the past are still adequate today. It’s this mindset the document is driving us towards, and appropriately so, no matter how much we might want to take a mental knee after over 13 years of very complex warfare, with even more to come.

But in many ways, the challenges of the future will likely be harder than they were in the past, as this increased connectedness raises the bar for achieving even a basic understanding of what is happening all around us. Highly destructive effects – brought directly to our Homeland at the speeds of sound and light as disruptive technologies, ideologies, and applications spread faster, wider, and more cheaply – will be increasingly available to smaller and smaller groups of bad actors, who will all-too-often be shielded and supported by traditional nation states using them as proxies to maintain plausible deniability for the actions they sponsor. But the challenge of dealing with increasing complexity is not just a military one – even if all of our wars miraculously ended tomorrow, we would still be challenged to understand what is happening in society as the world becomes ever more connected, with even the smallest ripples increasingly having faster and wider effects. Thomas Friedman may not have conclusively or persuasively proved that “The World is Flat,” but his observations about the “democratizations of information, technology, and finance” in The Lexus and the Olive Tree were apt, and help to explain why General Dempsey often recommends books like Present Shock and The End of Power to subordinates.

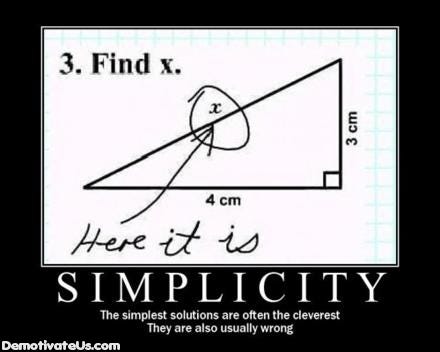

Bottom line: The days where you can get almost everything you need to know in a “Bottom Line Up Front” statement are over. Elegance is always to be sought, but in complex environments, “Keep It Simple Stupid” will increasingly become “Keep It Simple = Stupid” unless we successfully upgrade our own mental operating system through the development of more sophisticated operational and strategic concepts. More on that during the upcoming Innovation Week series here on The Bridge and at CIMSEC…

Bottom line: The days where you can get almost everything you need to know in a “Bottom Line Up Front” statement are over. Elegance is always to be sought, but in complex environments, “Keep It Simple Stupid” will increasingly become “Keep It Simple = Stupid” unless we successfully upgrade our own mental operating system through the development of more sophisticated operational and strategic concepts. More on that during the upcoming Innovation Week series here on The Bridge and at CIMSEC…

Win

Perhaps our greatest cognitive challenge will be defining what “winning” looks like in a world where “taking the gloves off” against an adversary has a much greater potential to provoke an even wider problem than seeking decisive defeat would. Our Iraqi experiences in 1991, 2003, and 2011 made it crystal clear that “winning” and “end states” are only mile markers in a sociopolitical journey that continue to emerge on their own accord no matter how we characterize them internally, reminiscent of the “Zen Master” story in Charlie Wilson’s War (Adult language warning).

In many cases, the time, effort, and risks to be taken in order to “win” in a systemic sense against some of our foes and their sponsors may be beyond the reach of our ways, means, and our nation’s will to sustain them given acceptable levels of risk. Seeking tactical success is always an imperative, but we must enter our conflicts wide-eyed to the strategic realities of engaging in “repair service” behavior when this occurs, as the AOC suggests. The AOC’s description of winning is incomplete in one sense, however. While “presenting the enemy multiple dilemmas” may indeed be a source of gaining continuing advantage – which may be the best we can do when a decisive win carries unpalatable costs – it does not resolve fundamental tensions that spark future violence.

In many cases, the time, effort, and risks to be taken in order to “win” in a systemic sense against some of our foes and their sponsors may be beyond the reach of our ways, means, and our nation’s will to sustain them given acceptable levels of risk. Seeking tactical success is always an imperative, but we must enter our conflicts wide-eyed to the strategic realities of engaging in “repair service” behavior when this occurs, as the AOC suggests. The AOC’s description of winning is incomplete in one sense, however. While “presenting the enemy multiple dilemmas” may indeed be a source of gaining continuing advantage – which may be the best we can do when a decisive win carries unpalatable costs – it does not resolve fundamental tensions that spark future violence.

Short of complete attrition, the only way to achieve that is to shape situations in which the previous enemy has become a nonviolent stakeholder in the same future you desire (or at least one close enough). Finding a “win-win” acceptable to you is truly winning in the strategic sense, even if human nature, unavoidable competition, and irreconcilable priorities often preclude such arrangements. So if we’re going to have to accept more nuanced interpretations of what it means to “win” in the future, why am I glad it was used – with no qualifications or asterisks – in the AOC title? Because it implies an attitude we must preserve at all costs, especially as we tackle the complexities of the modern world. And if the US Army ever stops believing that it can and will win, then God help us all…

Finding our Voice

The Narrative in the Army #Operating Concept

This post is another in the #Operating: A Personal Reflection on the Army Operating Concept series and was provided by Doctrine Man, America’s favorite comic anti-hero. The views expressed here are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army or the Department of Defense.

The Army has an identity crisis. After 13 years of waging war in remote corners of the world, we struggle to find our voice, our raison d’être. While our Sister Services posit a future where peer competitors present high-tech threats that limit our reach and influence, we fight for the words to describe our purpose in the world of today. Forget the future, we’re still arguing about yesterday.

Then along comes the Army Operating Concept, “Win in a Complex World.” Semantics aside (complexity is, after all, a relative term), the concept represents something very significant for a fundamentally-schizophrenic U.S. Army facing what just about anyone who can read would call simply “uncertainty.” Rather than a future where the Army stands on the sidelines as hypersonic missiles and fifth-generation fighters do battle over global commons rules by stealthy, fast-moving naval vessels, the concept imagines something far less glamorous over the horizon. A world that is crowded, urbanized, resource-starved. A world where asymmetry is a means of survival on the field of battle, fields that exist in heavily-populated urban sprawl, in the filth of the sewers beneath us, fought by an insidious enemy network able to change methods faster than we can adapt. Chaos.

Into this melee of death, dirt, and destruction, we launch the one weapon capable of bringing chaos to its knees: man. The human element. The ground-pounding foot soldier. Because the future isn’t Tom Cruise, it’s T.R. Fehrenbach, where the only way to prevail in the battle of wills is on the ground, in the mud, among the people. Chaos, ruled by men and women who thrive under chaos.

But the concept doesn’t offer any trillion-dollar silver bullets, so what possible value does it hold? There’s no mention of the hover-tank. It completely avoids any discussion of robotic super-soldiers. And for an entire generation of follicly-challenged Army officers, not one word on the cure for premature male baldness (a shocking oversight considering the mastermind behind the concept was none other than Dr. Evil himself, LTG H.R. McMaster). So what good is it?

The Army Operating Concept marks the opening stanzas of the long-neglected Strategic Landpower narrative. The answer to our identity crisis. It isn’t particularly elegant, and it tends to ramble from time-to-time. But it’s prophetic. It’s visionary. It’s part Black Hawk Down and part Starship Troopers, smeared with mud, blood, grease, and guts. It’s the answer to “Who are we?” and “Why do we fight?” It’s our narrative. Finally.

We found our voice.

Undue Emphasis of the Army #Operating Concept

This post is another in the #Operating: A Personal Reflection on the Army Operating Concept series and was provided by Krisjand Rothweiler, an U.S. Army strategic military intelligence officer. The views expressed belong to the author alone and do not represent the U.S. Army or the Department of Defense.

The Army Operating Concept (AOC) at the outset seeks to answer three big questions: What level of war will the concept address, what will be the operating environment and what is the problem that needs solving? The AOC then goes on to answer this in the preface and beyond with some examples that seem to miss the mark on both scope and nature of the environment as it pertains to the Army itself. After addressing many of the human aspects of conflict, the AOC starts looking at the technologies it might need in the future to wage war and build partners. While that is fine for external readers of the document, it leaves little comfort to the soldiers now serving that “big Army,” nor does it address the cost of service to the man or how to address this in order to continue the full-alert status the AOC seems to prepare for.

When discussing the environment, it would be appropriate to include the aspects impacting both friendly forces and threat. Yet from the outset, and continually through the document, the AOC seems to misunderstand the Army it addresses, particularly regarding the aspect of organizational culture. If the Army – an institution of people, not systems – is going to plan for the future of warfare, it has to understand itself today. In several instances, the AOC addresses human and intellectual attributes (creative thought and initiative, p. 5; the Army’s ability to establish a military government, p. 8; use of cognitive sciences, p. 13) that are seemingly inconsistent with the current culture of the Army (at the aggregate) and can only be truly developed with significant cultural shift.

If the Army is to meet the intent of remaining a professional, all volunteer force AND develop the desired attributes of intellect, initiative and trustworthy, autonomous leaders WHILE remaining in constant contact with multiple partners and adversaries and reducing spending, the current system will have to change. Recruiting, training, education and retention must begin to address the individual. Physical training needs to mirror the athlete and education to mirror the scholar where development and enhancement are utilized more and recovery and repair are needed less.

A secondary area receiving undue emphasis is the role of technology on the environment. After opening with a discussion of the “contest of wills” and the importance of capability in the context of endurance, the AOC puts significant emphasis on the use of technology to make the Army better and more capable. Admittedly, technology can be a powerful thing when used appropriately, but finding the funding balance between gadgets and field time is critical. In the past 100 years, most major conflicts have not been won through superior technology, but through superior training and desire. The Germans in the 1940s had many technological advantages yet lost to Allied will and volume. In today’s world, the commitment of violent radicals to their cause or a cartel to illicit income is able to circumvent U.S. technological capacity more days than not.

As part of a joint force, the Army is the singular service that needs the man more than the machine. Had the AOC ended with using technology to enhance superior training, it may have been on the mark. But by setting the stage to maintain budgetary pace with the other services, the Army may find itself in 2020 with rooms of gear and no one to use it. The AOC should instead concede that the Army need not be a high-tech service, but leave that to the other branches of the military. Instead, the AOC should make the case for improving the person; investing in training, improvement physically and mentally and allowing the flexibility for the person to support the ally or control the enemy.

Operationalizing the Army #Operating Concept

This post is another in the #Operating: A Personal Reflection on the Army Operating Concept series and was provided by Chad Pillai, an U.S. Army strategist. The views expressed belong to the author alone and do not represent the U.S. Army or the Department of Defense.

I want to open and close this essay with my philosophy drawn from my father, a senior budget analyst in the New York State Budget Division, and a very influential supervisor I worked for in the Pentagon who reinforced his thoughts on defense policy by stating that “Funding is policy, and all else is rhetoric!” So, how does this relate to the AOC? A successful AOC drives the Army budget in transforming itself operationally and institutionally. Plainly speaking, the Army needs to put its money where its mouth is.

In the near, mid, and far terms, the Army faces numerous challenges ranging from transnational terrorist organizations to state near-peer competitors. However, the Army’s single biggest challenge will be future Army funding levels resulting from the Budget Control Act (sequestration). Simply going to Congress asking for more resources to meet the Army’s operational requirements is no longer a viable approach. There are two reasons for this. First, as the threats in the Operational Environment (OE) mature, the other services will need to invest in expensive modern programs to overcome high-end A2/D2 platforms from emerging near-peer competitors – programs that are beneficial to congressional districts. Also, as I stated in my War on the Rocks (WOTR) article, “The Return of Great Power Politics”, the nation’s and, by extension, the joint force’s ability to address global security challenges will be challenged as Russia and China increasingly seek to constrain our actions in an increasingly multipolar world. The second reason is domestic politics in the ongoing “Guns vs. Butter” debate as the nation’s fiscal challenges exacerbate the budgetary struggle for funding between defense, the social safety net, and investment on infrastructure and education.

The mixtures of conventional and asymmetrical threats compounded by budgetary uncertainty are the ingredients for complexity stated in the AOC. To address this complexity, the AOC states “The Army will adjust to fiscal constraints and have resources sufficient to preserve the balance of readiness, force structure, and modernization necessary to meet the demands of the national defense strategy in the mid- to far-term (2020 to 2040).” That sentence above all others raised my suspicions on the effectiveness of the AOC based on my experience with the Army’s “Force 2025 & Beyond” initiative. Participants at the Center of Gravity (COG) analysis for “Force 2025 & Beyond,” determined the Army’s budget was the COG, with the justification being that the budget would be the single greatest determinate of how the Army balanced General Odierno’s “Three Rheostats: Force Structure, Modernization, and Readiness.” Members of the G-8 challenged the budget as the COG, citing “requirements” as the COG, but that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny if the Army can only afford to pay for 8 out of the top 10 requirements. So, with the budget as the COG, how can the Army operationalize the AOC? Balancing the three rheostats is the easy answer, yet this is not so easy when certain variables lie beyond the Army’s control.

The Defense Planning Guidance and subsequent Quadrennial Defense Review limited the Army’s flexibility through mandated force structure cuts by calling for endstrength reductions from a wartime high of 560K to 450K active duty, with further cuts needed if full sequestration goes into effect. While forced to cut endstrength, despite an increased demand for land forces globally, the Army has been unable to get Congressional authorization to shed excess basing and facilities infrastructure to save money. Modernization efforts such as the Future Combat System, Crusader, Comanche, the network, and even the Army’s camouflage pattern have exposed the Army’s acquisition shortfalls in the past two decades that have caused the ire of Congress and the public. Additional constraints on modernization include Congressional resistance to the discontinuation of the Abrams tank production line to free up modernization funds – a similar lesson to that the Air Force learned in attempting to terminate platforms such as the A-10. The only flexibility the Army has is with readiness. To accelerate modernization, the “Force 2025 and Beyond” initiative seeks to reform the Army’s acquisition model by increasing effectiveness and efficiency, coupled with continuous assessment of programs to build, field, and equip forces in the lifecycle of new technologies. This has to be done in the speed of adaption driven by friendly or enemy breakthroughs in concepts and/or technologies.

To meet the operational tenets of the AOC, the Army needs to provide forces capable of rapidly responding to threats to our security. This creates a Catch-22 dilemma as the Army cuts endstrength while demands for readiness increases. In a recent speech, the TRADOC Commander said “The Army equips the Man while the other Services man the equipment.” I partially disagree with this statement since the quality of our air and sea platforms is equally based on the high level of training and education of the personnel assigned to those platforms as Soldiers assigned as members of an Abrams tank, M109 Howitzer, Patriot Battery, and Apache Helicopter. In all domains, the performance of equipment is a direct reflection of the quality of the people trained to employ that equipment. Either way, how the Army utilizes its Soldiers will determine the success of the AOC in overcoming the Catch-22 dilemma.

In an internal strategist e-mail titled “Transitioning from the Spear to the Sword”, I highlighted that the Army was mandated by the Secretary of Defense to cut headquarters by 20 percent. However, I noted that a lot of the cuts are budgetary shell games done by reducing the size of the contractor workforce, freeze hiring, and normal attrition form retirements. At the same time, the Army accepts risk by cutting deeper into the operational forces needed by Joint Force Commanders to address the challenges identified in the AOC. I argued that before the Army went to Congress seeking more resources, it needed to make radical changes to its institutional structure, like a corporate restructuring, that placed greater emphasis on the operational force (the product/service demanded) vs. the institutional force. The target for such restructuring was not the schools and training centers needed to prepare the force, but rather the multitude of institutional headquarters and agencies that perform overlapping and redundant functions and have been a misallocation of personnel and resources.

Headquarters of the Department of the Army (HQDA) and its supporting agencies are too large and share many responsibilities with subordinate Army Major Commands (ACOMs) such as Army Materiel Command (AMC), Forces Command (FORSCOM), and Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC). HQDA needs to be trimmed in half and devolution of authorities needs to be push down to the ACOMs. TRADOC and FORSCOM should be merged to perform the Army G-3 function, since neither command in the post-Goldwaters-Nicholas Act construct will command army forces in combat even if a major expansion is required. Wholesale restructuring of the Army’s corporate enterprise will force the Army to transfer more of its personnel from corporate/institutional support to operational assignments; thereby ensuring units are fully-manned and ready for operational tasks.

Utilizing the AOC as a blueprint for the future, the Army needs to build a “POM-Trace” to carefully track and integrate acquisition programs for modernization; incorporate existing weapons platforms and emerging platforms into the tenets of the AOC and how units are assessed for readiness; and implement major corporate restructuring to demonstrate good faith efforts in utilizing existing budgetary resources. This will bolster the Army’s means to operationalize the AOC and make more compelling arguments for an increase in resources from Congress. As I stated in the beginning, “Funding is policy and all else is rhetoric.” If the Army operationalizes the AOC to drive the budget rather than be driven the by budget, it will be successful.

The Army #Operating Concept and Allies

This post is another in the #Operating: A Personal Reflection on the Army Operating Concept series and was provided by J.P. Clark, an U.S. Army Strategist currently serving in London. The views expressed here are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or his host country’s chain-of-command.

One of the most ambitious and praiseworthy original aspects of the Army Operating Concept (AOC) is the expansion of its scope to include the strategic and tactical levels of war. As General David G. Perkins reminds us in his preface, “‘Win’ occurs at the strategic level and involves more than just firepower.” Certainly, there are few who would explicitly argue for us to pursue a “strategy of tactics.” Fewer still would dispute Perkins’s Clausewitzian notion that the purpose of an army is to get to the “Strategic Win.” Yet, by its very nature, an operating concept is naturally drawn toward idealized ways of war stripped of strategic and political context, and so we should appreciate the boldness of the effort to break out of this structural trap. Though this aim is achieved in some instances, for the most part this edition of the AOC is more rather than less like previous iterations. Though I cannot offer a complete answer to what an operating concept geared toward getting to the strategic win might look like, I do have a few suggestions toward that aim.

First, I have a few comments on the AOC as an operating concept from the standpoint of a US exchange officer serving in an allied army headquarters. One of the lessons earlier generations of Army officers understood is that sometimes you have to forego the tactics that you would like to use for those that are appropriate to the kind of army you will fight with. In the nineteenth century, that meant tacticians like Emory Upton developed tactics fit not to the tastes of the experienced officers and well-drilled soldiers of the regular army, but for the inexperienced and untrained volunteers who would serve as the privates, non-commissioned officers, junior and even senior officers of a wartime force. The present-day manifestation of this is the need to shape our concepts and doctrine to a coalition force.

We must do so for the simple reason of resources. The cost curves of personnel and equipment and the likely level of future budgets means that, barring the always possible strategic and political shock, we will be a considerably smaller force in 2025 than we are today. Yet, this is not simply a question of pessimism about the future. Any reader of “The Bridge” can imagine a plausible scenario in which one of the several on-going crises causes us to act, but in which the US military at today’s force levels simply does not have the capacity to achieve our desired strategic aims. We may have already crossed the threshold in which we more often than not willneed allies rather than simply welcome them. We have a number of staunch allies, the kind we can depend upon for a battalion, brigade, or division, if we face a situation so dire it exceeds our unilateral capability. (As an aside, our constant rejoinder to our air and naval comrades is that armies are the coin of the realm in those high-risk cases; this means we should follow the trail of our own logic and keep that kind of extreme case in our focus.) We need to regain the lost art of simplicity at the tactical and operational levels, as coalitions are inherently less effective tactically and operationally than a single force manned, trained, and equipped to a common standard.

So, how does the AOC look as a template for combined operations? The rapid transitions between dispersed operations and concentration envisioned by the AOC imply what might well be an unreachable goal for force developers in even our best, most capable allies, for they post multiple problems, particularly in a time when all face similar resource pressures. From an ally’s perspective, how are you going to afford the investments to maintain interoperability with the mission command networks, reach the necessary level of intelligence sharing (particularly for those outside “Five Eyes”), deconflict fires, avoid fratricide, and sustain forces? Aside from the likely question of interoperability, the concept suggests a high level of training that is likely beyond the bounds of even the best alliance.

Frankly, I doubt our own ability to achieve the AOC. The jury is obviously still out, for this is a concept and not doctrine. Furthermore, the significant institutional impetus exerted through the Force 2025 will undoubtedly yield excellent results. Nonetheless, the concept in AOC is unpleasantly reminiscent of some of the ideas underpinning the Pentomic Army. The agility described seems too dependent upon the functioning of our digital and space systems, which the AOC notes will be vulnerable in the future, as well as depending upon the reliable working of some technology that we have not even developed yet. Certainly, with a few years of hard experimentation and training, we can probably get to the point where it can work against some enemies, but I fear that it is too complex for use against a particularly capable and well-resourced adversary, or perhaps one who is simply particularly clever in the way that they leverage dual-use civilian technologies.

I understand the pressures that drove the AOC: adverse ratios of force to terrain; the likelihood of operating in urban areas in which flash mobs can be readily mobilized through social media; loss of intelligence dominance due to smart phones and ubiquitous UAVs; swarming autonomous systems; contested air and sea lines of communication; network and space attack; proliferation of WMD; and, most likely, something it has not even occurred to us to be afraid of…yet. In light of this context, TRADOC could hardly issue an AOC touting stolid immobility and reliance on current processes. Concepts are supposed to push the boundaries of what is possible. Nonetheless, I fear that perhaps, like a century ago, we might be in a place where there just is no good tactical-operational solution. If so, then rather than wrestle with an insoluble problem, we should try to make the problem bigger.

This brings us back to the “strategic win.” As the remaining superpower, we are inherently a status quo power. Although I cannot put my finger upon it, I think that should somehow be the cornerstone of our concept for getting to the strategic win. Thus, for instance, rather than trying to develop a way to “win” in a mega-city, we should attempt to figure out how to do the best we can within a mega-city but focus more of our thought on translating whatever that is into strategic effect.

Our other great strategic advantage is the existing network of allies we have and the likelihood it will only increase if the world gets darker. Coalitions bring some tactical-operational liabilities due to differences in language, kit, and modes of working. Most of the references to “multinational” relate to minimizing these and so are really meant in the sense of trying to make our partners look as much like us as possible. But there are also strengths in a coalition and there is no discussion whatsoever in the AOC of how we might leverage those to our advantage. Several come immediately to mind: the diversity of tactical technique and equipment might pose dilemmas for an adversary; similarly, the diversity of equipment provides resilience to cyber-attacks geared to American systems; some partners might have greater legitimacy with the population; some partners might have greater regional or functional expertise. Most importantly, coalitions can bring mass we are apt to desperately need. There are many who ridicule the diminishing capacity of NATO, but we will soon be to the point where saying an ally can “only” bring a battalion or brigade will seem quaint.

Perhaps more importantly, since getting to the strategic win is our goal, allies and partners can bring international legitimacy, basing and access, and the intangible aspect of their own political and strategic influence. This last element derives from any number of sources — history, culture, religion, economy — that might be what we need to achieve our strategic aims. Before now, I would have thought such factors were outside of the purview of the AOC. On reflection, I now realize how wrong I was. We do need to think about how we get to the strategic win, and the Army should think about how that consideration should influence our conduct of operations. That is a very big question we can all pitch into.

The Army #Operating Concept’s Global Landpower Network

Challenges and Cautions

This post is another in the #Operating: A Personal Reflection on the Army Operating Concept series and was provided by Ray Kimball, an U.S. Army Strategist. Ray was one of the many soldiers that took part in the development of the AOC by reviewing and providing comment. The views expressed here are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of the US Army, the Department of Defense, or the Global Integrated Joint Operating Entity.

There’s a lot to like in the new U.S. Army Operating Concept (AOC): Win in a Complex World. Any government document with 65 endnotes and a Thucydides call-out in its first three pages can’t be all bad. The AOC is appropriately wide-ranging, covering the full range of Army missions. This piece will focus narrowly on an AOC concept that is mentioned, but not significantly fleshed out: the global landpower network.

The idea of a global landpower network (which I’ll abbreviate to GLN because everyone loves a good acronym) revolves around a central aim: Create and sustain relationships with allies and partners that will build confidence, deter conflict, and if necessary, provide forces for a combined campaign. It calls on conventional and special operations forces alike to build these relationships through theater security cooperation activities, presumably ranging from individual schooling all the way to combined maneuver exercises. The idea reflects the significant success of the State Partnership Program, a post-Cold War initiative that joined National Guard forces with post-Soviet militaries to build up their capacity. It also echoes similar service initiatives like the U.S. Navy’s “Thousand Ship Navy”, which unfortunately seems to have been overcome by events.

The greatest challenge to the noble goal of a GLN is the persistent and pervasive weakness of many of our allies and partners. The Royal Netherlands Army recently sold the last remnants of its armored force to the Finns, and the British Army is in the midst of radical changes to both its operating capabilities and force structure. Other allies are hobbled by persistent political and social restraints; witness the Turkish Army’sinability to engage ISIS elements in artillery range or the Thai Army’s turning back of the clock in that country’s democratic system. U.S. officials’ perennial pleas at NATO and other security forums for other countries to maintain some semblance of military capability have become the Carthago delenda est of the 21st century. The three-headed monster of Russian revanchism, Chinese muscle-flexing, and an Islamic Thirty Years’ War have prompted some states to begin re-evaluating their defense force posture. But it is not yet clear if those concerns will materialize into action in an era where the Euro is still shaky at best and Pacific allies take frequent opportunities to poke at one another.

As a consequence, the other members of a GLN will not fight the way we do. It will not be the equivalent of the good old days of Allied Command Europe, where the difference between Allied land forces was mostly in quantity rather than quality and operational concepts. To illustrate this, we need look no further than the tenets guiding the application of combat power listed in the AOC (paragraph 3–4, for those of you playing along at home). Three of those tenets (Simultaneity, Depth, and Endurance) are heavily dependent on Mass, that persistent principle of war that continues to rear its ugly head in opposition to some of the more outlandish claims of network-centric warfare. Our allies and partners in a GLN simply won’t have the deep bench necessary to fully implement those tenets of warfare.

That doesn’t mean the idea of a GLN is DOA; it does mean we need to keep some provisos in mind when planning for its use:

Networks involve a two-way exchange of ideas and information. A GLN conceived solely as a U.S. means to disseminate tactics and old equipment is doomed to failure because it requires altruism as a precondition for sustainment. Just because our network partners don’t fight like us doesn’t mean they don’t have things to teach us. Many of them have learned hard-won lessons on how to get the most out of a tight defense budget, something we could use a little brushing up on. Some of them may have equipment we can procure in low quantities to meet time-sensitive needs. A two-way exchange doesn’t mean playing games where we pretend everyone is equal, but instead involves candid conversations about what each member brings to the table.

Don’t fear the caveats; work with them. Our ISAF experience shows us that members of a GLN are going to operate with caveats; those dreaded limitations of operational mission or tactics imposed by national capitals. Faced with these, most U.S. officers roll their eyes and mutter some version of Churchill’s famous quote about fighting with Allies. But if we’re being honest, we ought to acknowledge that we, too, operate with caveats, whether it’s “no boots on the ground” or the limitations ofposse comitatus. Caveats are a pain, but not an insurmountable obstacle. The sooner we acknowledge them, the sooner we can find ways to work with them.

U.S. enablers are going to play a bigger role than maneuver forces.Few GLN assets will be willing to be plugged into a U.S. maneuver formation due to the limitations discussed above. That means many of them will operate independently or in remote locations. Many of these partners will struggle just to deploy their assets to an austere environment; sustainment of those same assets in a dispersed manner will be beyond them. U.S. enablers, including MEDEVAC, fuel, and mobility assets, are going to be the coin of the realm to sustain GLN participation in a protracted mission. Again, this isn’t wildly different from our own needs; in fact, the logistics requirements of supporting a GLN can be a powerful argument for retaining these capabilities in the face of yet another round of “tooth-to-tail” arguments.

A GLN that effectively integrates allies and partners, warts and all, into our operations is a goal worth pursuing.

The Army #Operating Concept

An Insider’s Perspective

This post is another in the #Operating: A Personal Reflection on the Army Operating Concept series and was provided by Daniel Sukman, an U.S. Army strategist. Full disclosure: the author works at the Army Capabilities Integration Center (ARCIC), the organization responsible for the production of the AOC. The views expressed here are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of the US Army, the Department of Defense, or any other organization of the US Government.

The recently published 2014 Army Operating Concept (AOC) broadly defines how the Army will operate in the near, mid, and far terms. In a bureaucratic sense, the AOC defines capabilities that are required of an Army that will one day make its way through the JCIDS process. However, from a personal perspective, the AOC represents a challenge. It is a challenge to the warfighters and leaders who have been a part of an Army at war for the past thirteen years. To me, the AOC is a challenge to shape and form the Army and its future leaders and build the foundations of its success in the years to come.

From a strategic perspective, the AOC discusses what conflicts may look like through the lens of current conflicts. ISIL, Russia, and North Korea certainly represent challenges to Combatant Commanders today. In 2025 and beyond, the crisis with Ukraine and Russia may be over, but the “little green man” challenge may pop up in another theater. ISIL may be a remnant of history, but radical groups bent on death and destruction will still be a threat to the United States and our friends and allies.

In 2007, I deployed to central Baghdad as a company commander in 2nd Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division. This was my second deployment with the STRIKE Brigade Combat Team, the previous deployment having been immortalized in Jim Fredrick’s book Blackhearts. Although the mission, outcome, and location of these two deployments were disparate, they shared a common aura of certainty in the year prior to each. For a tactical unit (Division and below), the future was, to a large extent, certain. Although counterinsurgency is complex, the total environment was not.

This complexity has not been ingrained over the past decade and a half. Senior officers and NCOs of my generation will be challenged to create training environments that consider all domains and multiple battlefields. This is a new paradigm. The 2014 Army Operating Concept discusses complexity when it states “The complexity of future armed conflict, therefore, will require Army forces capable of conducting missions in the homeland or in foreign lands including defense support to civil authorities, international disaster relief and humanitarian assistance, security cooperation activities, crisis response, or large-scale operations.”[i] While the Army did conduct missions other than Afghanistan and Iraq over the past 13 years (e.g. Hurricane Katrina Relief Operations), the overwhelming majority of units were singularly-focused on the Central Command Area Of Responsibility (AOR). Home station and Combined Training Center (CTC) training did not have to consider other complex mission sets.

Further complexity will revolve around how the Army gets into a theater of operations. Backing up the ideas in the Joint Concept for Operational Access and the Joint Concept for Entry Operations, the AOC states “Army forcible and early entry forces, protected by joint air and missile defense, achieve surprise and bypass or overcome enemy anti-access and area denial capabilities through intertheater and intratheater maneuver to multiple locations.”[ii] Company, battalion, and brigade commanders deployed with the assumptions of air superiority, and that entry into a theater of operations would be unopposed.

As the Army moves past nearly 14 years of combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, the future mission sets of Brigade Combat Teams is uncertain, unpredictable, and complex. That young company commander I spoke about earlier will no longer have certainty in his or her future. Company commanders deploying to West Africa to assist nations struggling to contain the Ebola virus do not enjoy the luxuries I had as a commander. Three or four months prior to their deployment, they may have never heard of Ebola or even have seen Dustin Hoffman in Outbreak. They did not have a decade’s worth of intelligence and contacts in what will be their Areas of Operation. There is no Pre-Deployment Site Survey (PDSS), no left seat/right seat ride transition, and no CTC rotation that mimics West Africa.

Moreover, those Company Commanders fighting Ebola will not have the luxury of stopping at the Green Bean Café on the morning of a mission. Deployments going forward will be more expeditionary in nature and mindset. Expeditionary is not always the speed of deployment, but at times the austere conditions Soldiers will operate in. There are no containerized Housing Units, no Foreign Operating Base Mayor’s cell to fix the internet, and no Brown and Root dining facility. There may not be port-o-johns either. The expeditionary mindset will be prevalent throughout the Army.

Another factor the Army Operating Concept recognizes is the requirement to operate with Joint, Interorganizational, and Multinational (JIM) partners. Again, going back to 2007, it was a given that a Company Commander would have to integrate operations with local security forces, and possibly some state department personnel. Seven years later, not only does that Company Commander have to work with host nation security forces, but s/he is likely to take direction (not necessarily command) from members of the World Health Organization or the Centers for Disease Control.

As stated in the AOC, the Army “creates multiple options for responding to and resolving crises.” A crisis can occur at any position along the Range Of Military Options (ROMO). Preparing to operate across the ROMO will be a new mindset. Again, as a commander in 2007, the ROMO was narrowed in scope to counterinsurgency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. The only connotation ROMO had was a quarterback who consistently blew fourth quarter leads. Furthermore, company commanders in the future will be required to respond globally to crisis, not limited to two countries in central Asia.

As a leader who commissioned in 2000, just prior to the start of the Global War on Terror, I predict the 2014 Army Operating Concept will drive a change in mindset. As mentioned previously, today’s company commanders, platoon leaders, and junior NCOs will face a myriad of problem sets that may not resemble what senior level officers and NCOs have faced. This younger generation of leaders will grow up in a different Army. Just like those who grew up in the Army of the 1990s, conducting National Training Center rotations preparing for Major Combat Operations had to adjust to counterinsurgency, likewise those of us who grew up in an era of counterinsurgency will be forced to learn and relearn combined arms maneuver at the brigade and division level.

Finally, the AOC places the onus on my generation of officers to develop the next generation of leaders. The AOC states “Adaptive leaders possess many different skills and qualities that allow the Army to retain the initiative. Army leaders think critically, are comfortable with ambiguity, accept prudent risk, assess the situation continuously, develop innovative solutions to problems, and remain mentally and physically agile to capitalize on opportunities.” Those leaders will be developed and taught by a generation of combat tested officers and NCOs. I relate this to a time in 2000, when I was a young second lieutenant stationed in Korea. The only members of my battalion wearing combat patches were the field grade officers and senior NCOs who participated in Desert Storm or in combat operations in Somalia. In the next few years, senior leaders will have to recognize that we cannot rest on our laurels, as the ranks will be filled with inexperienced Soldiers who may go an entire enlistment without a combat deployment. Those Soldiers and their families will expect to be trained and prepared for combat, should the time come that they’re called to engage in it. The AOC demands that leaders prepare our Army for conflict, wherever, and whenever that may be.

[i] 2014 Army Operating Concept. Paragraph 2–6

[ii] Paragraph 3–3.b

#Operating

Beginning a Discussion on the Army Operating Concept

The new Army Operating Concept (AOC) posted earlier this week received a lot of feedback on social media and in the halls of military installations – which ultimately led to this series, titled “#Operating: A Personal Reflection on the Army Operating Concept,” on The Bridge. This post will kick things off by taking a holistic look at the document; later posts will focus on personal reactions to the document – what it says, what it fails to say, or even particular elements from it that resonate.

To begin, the framing of this future-oriented document is solidly rooted in the past…something we should all expect given that the overseer of its publication is the noted Warrior-Historian, LTG H.R. McMaster. A military document that not only references in the endnotes historical analysis and theory found in texts like those by Thucydides, Clausewitz, and even past military doctrine, but also conceptually intertwines their wisdom throughout, is likely to be more valuable than a document typified by “buzzword bingo.” While professional vernacular is a tool to accurately and quickly convey terms among members of the profession, it can also be used to gloss over or even replace deep thought and vital understanding, even among the “initiated.” So, while the AOC certainly reduces its use of typical military language from previous versions, it does still contain its fair share of jargon.

For the uninitiated, the AOC is supposed to “describe how the Army…employs forces and capabilities…to accomplish campaign objectives and protect U.S. national interests” (Page 8). It takes a little digging to find that in this document. To make things a little easier (at least for me), I’m going to break out some key elements and translate its contents into my language, hopefully increasing the accessibility of the concepts.

First, what problem is the AOC trying to solve?

“3–1. Military problem: To meet the demands of the future strategic environment in 2025 and beyond, how does the Army conduct joint operations promptly, in sufficient scale, and for ample duration to prevent conflict, shape security environments, and win wars?” (Page 14)

Translation: How does the Army “prevent, shape, and win” 1) promptly enough for political leaders and to address the military issue at hand; 2) at a sufficient scale to achieve military and political objectives; and 3) for an ample duration to create an enduring, positive effect.

For me, the question remains if the Army (or any military Service) can do all three of these items in a resource-robust environment, let alone a fiscally-constrained one? For instance, I think the Army (and all the Services) provided the capability to be prompt and enduring in the last few conflicts…but for many reasons (political and military), scale was another issue.

Now, what is the solution to this military problem (what the AOC terms the “Central Idea”):

“3–2. Central idea: The Army, as part of joint, interorganizational, and multinational teams, protects the homeland and engages regionally to prevent conflict, shape security environments, and create multiple options for responding to and resolving crises. When called upon, globally responsive combined arms teams maneuver from multiple locations and domains to present multiple dilemmas to the enemy, limit enemy options, avoid enemy strengths, and attack enemy weaknesses. Forces tailored rapidly to the mission will exercise mission command and integrate joint, interorganizational, and multinational capabilities. Army forces adapt continuously to seize, retain, and exploit the initiative. Army forces defeat enemy organizations, control terrain, secure populations, consolidate gains, and preserve joint force freedom of movement and action in the land, air, maritime, space, and cyberspace domains” (Page 15).

I did mention this document, while rooted in history, still contains a bit of military jargon. So, here’s my interpretation/translation of this dense paragraph:

The Army must prevent and shape conflict by engaging regionally (thereby being able to develop partners capable of providing local/regional security and stability, as well as assure allies to prevent miscalculation) and respond globally with credibility (to deter adversaries). Additionally, the Army, when necessary, “presents multiple dilemmas” and “limits enemy options” when conducting combat operations against an adversary; this will theoretically compel an enemy to submit to our desired military and political objectives.

How will the Army operate to achieve this solution? I won’t quote the ten paragraphs, but instead provide my interpretation (I think some of them are subsets of others or redundant, so my list is a little shorter). The Army will:

Be regionally engaged – provides access and intelligence/understanding of the area, as well as increases partner capabilities and assures allies in the region.

Be globally responsive – provides ability to project power and deter adversaries.

Conduct combined arms operations – in support of Joint Force and that CAN BE sustained for long periods.

Be capable of controlling adversaries and populations – this is accomplished through security, presence, and support local civil authorities.

Build/shape Army forces that can do the four items above – this is done through the Army’s Title 10 responsibilities (design, man, train, equip), of which leader/people development is an important subset.

When I read a list like the above, what it tells me is the Army must be capable and willing to regionalize its units, operations, and paradigm. The Regionally Aligned Forces concept largely addresses this, but structural issues must be overcome to drive it even further. The AOC touches frequently on one of those structural items; set the theater capabilities. In order to deploy, employ, and sustain units – even inside the U.S. – maneuver and maneuver support units must have the infrastructure to operate. This includes “essential capabilities including logistics, communications, intelligence, long-range fires, and air and missile defense” (Page 21). If the Army wants units regionally engaged and globally responsive, then capabilities to conduct those activities – as well as those that support them – they should be assigned to the regional military authorities; the Combatant Commanders. Underneath each Combatant Commander is an Army headquarters element charged with being regionally aligned and capable of setting the theater; the Army Service Component Command. Resourcing and empowering it with set the theater capabilities, assigned forces, and more robust planning elements would greatly enhance the Army’s ability to achieve the first two bullets above.

Placing the “set the theater” activity as a core element of how the Army operates is one of the greatest strengths in the new AOC – and one that is frequently overlooked by the Army, as well as the other Services and DoD as a whole.

Finally, the laundry list of “required capabilities” in the AOC does not really address capabilities, but activities the Army needs to perform (i.e. intelligence collection, SFA, command and control forces, etc.) (Page 29). The true capabilities are addressed later when the AOC details, “future force development principles” (Page 33). They include:

Retain capacity and readiness to accomplish missions that support achieving national objectives.

Build or expand new capabilities to cope with emerging threats or achieve overmatch.

Maintain U.S. Army asymmetrical advantages.

Maintain essential theater foundational and enabling capabilities.

Prioritize organizations and competencies that are most difficult to train and regenerate.

Cut unnecessary overhead to retain fighting capacity and decentralize capabilities whenever possible.

Maintain and expand synergies between the operating force and the institutional Army.

Optimize performance of the Army through a force mix that accentuates relative strengths and mitigates weaknesses of each component.

I know there are different interpretations of the purpose of the AOC, but I believe the above items are what the Army should have focused on in the AOC – these are the capabilities required that would allow further analysis and experimentation to flesh out “how” the Army should operate in the future. After the admirable description of the operating environment (well-rooted in the past), the AOC could have detailed these items and used them to drive how the Army would achieve them in the future – a vision for an Army that can operate consistently across the world day-to-day, but coalesce on specific areas to conduct combined arms operations against defined enemies to achieve political objectives through military force.

The Army continues to consolidate and articulate its means and ways as we venture into the future…and the new AOC is one element of how the Army, as an institution, drives that change.

No comments:

Post a Comment