Nigeria’s top general Alex Badeh announced on Oct. 17 that the government and insurgent group Boko Haram had agreed to an immediate ceasefire.

And only a day later, top presidential aid Hassan Tukur told Voice of America that Boko Haram had “agreed in principle” to release the 217 girls the group had taken hostage in the northern town of Chibok almost exactly six months ago.

This is great news on the face of it. The conflict between Boko Haram and Nigeria’s government has killed as many as 17,500 people since 2011 alone. Whole communities burned, thousands fled their homes and lost their livelihoods.

But what we know about the purported ceasefire raises more questions than it answers. Be hopeful … and skeptical.

But what we know about the purported ceasefire raises more questions than it answers. Be hopeful … and skeptical.

A frozen conflict?

The ceasefire is surprising in part because in recent weeks the Nigerian army has, for the first time, been moderately successful in combating Boko Haram. The army won an important victory at Damboa and even claimed to have killed Boko Haram’s leader.

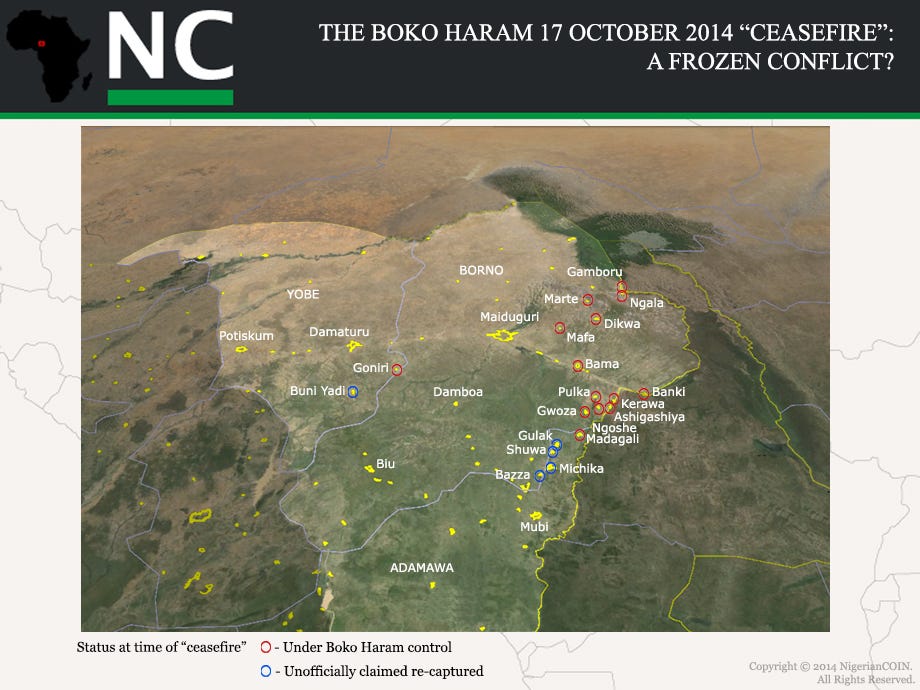

Now Badeh has explicitly stated that the Nigerian army will cease all attacks against Boko Haram, even though the group still holds considerable territory and controls whole communities.

For the Nigerian state, this is an unacceptable situation, especially as the country has presidential elections coming up in 2015. We don’t know the details of the ceasefire, but we can assume the government will push for the militants to turn over more territory.

There are also questions about the legitimacy of the negotiations taking place in Nigeria’s neighbor Chad. Boko Haram’s representative in the talks is Danladi Ahmadu. Nigerian and international Boko Haram experts were unaware of this individual before his first appearances in international media—and so far their contacts inside the group haven’t confirmed his identity.

Discrepancies underscore doubts about Ahmadu’s legitimacy. In an interview with Voice of America, he used the unofficial name Boko Haram to refer to the group, even though Boko Haram’s own leaders have always used its official name, Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad.

Discrepancies underscore doubts about Ahmadu’s legitimacy. In an interview with Voice of America, he used the unofficial name Boko Haram to refer to the group, even though Boko Haram’s own leaders have always used its official name, Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad.

Above—a demonstration in Abuja on Oct. 14. AP photo/Olamikan Gbemiga. At top—the Chibok girls. AP file photo

The girls and the politics

Along with the ceasefire, the Nigerian government announced that it’s close to striking a deal with Boko Haram to free the more than 200 schoolgirls the militants abducted from Chibok.

The girls’ plight became an Internet phenomenon six months ago, when a campaign to pressure the Nigerian government into acting used the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls to raise awareness.

The administration of president Goodluck Jonathan made no mention of the more than 300 other girls and women Boko Haram is apparently holding captive. Nor did the administration specify the conditions that will secure the Chibok girls’ release.

Jonathan is expected to formally announce his candidacy for the 2015 elections in the coming days or weeks. A glimmer of hope for the release of the Chibok girls, as well as a negotiated settlement of the country’s civil war, provides just the right backdrop for his campaign kick-off.

All this good news could actually be empty politicking.

The Nigerian government and army don’t exactly have the best record when it comes to providing accurate information on the conflict with Boko Haram.

We may even have to wait for one of the militant group’s better-known leaders to come forward, before we can be sure that the conflict’s dynamics are truly changing.

https://medium.com/war-is-boring/maybe-the-war-in-nigeria-is-ending-maybe-its-not-c5bf95e244ba

No comments:

Post a Comment