The Battle for Jalawla Never Ends

As the Kurds fight Islamic State, this small town near the Iranian border has frequently changed hands

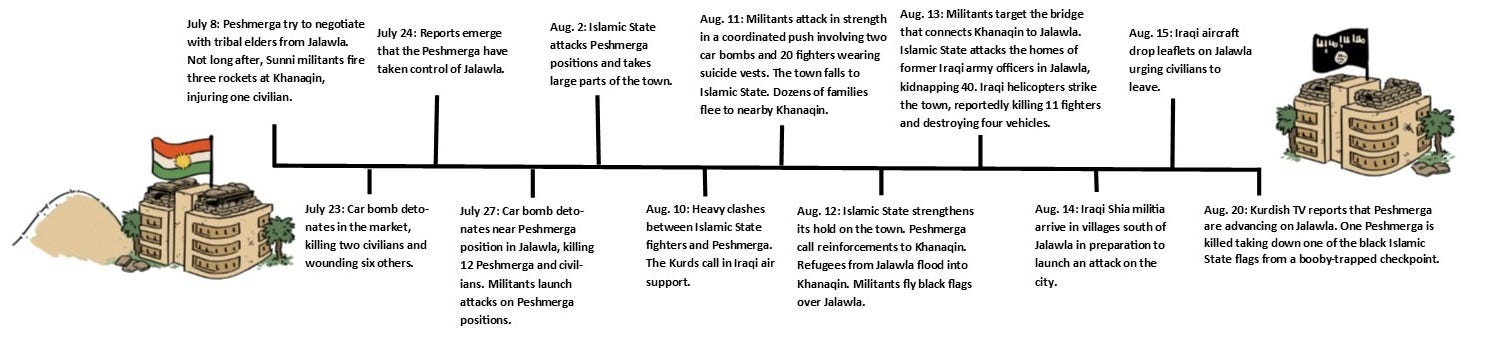

The back-and-forth fight over the town of Jalawla in northern Iraq has been one of the fiercest clashes of the expanding war on Islamic State. Since June, Kurdish Peshmerga fighters and Islamic militants have taken turns controlling the historic town 170 kilometers north of Baghdad and just five kilometers from the Iranian border.

There’s a long, nasty history here. And for the Kurds, especially, Jalawla has symbolic importance.

Decades ago, Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist “Arabization” programs drove many Kurdish families out of the town. Today Islamic State’s Iraqi supporters include many former Ba’athists. For that reason among others, the Pesh have been adamant about holding Jalawla.

The seesaw combat has also exposed the Kurds’ internal divisions. In early summer, the Peshmerga force included troops loyal to the ruling Kurdish Democratic Party and also fighters answering to the rival Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. But now the KDP Pesh have withdrawn, leaving the PUK forces to fight alone.

After months of street fighting, Islamic State has forced the Peshmerga out of Jalawla. But the Kurdish forces remain on the edges of the city—and from there, trade artillery and machine gun fire with the militants in the city. Snipers prowl both sides, threatening their enemies with sudden death.

As War Is Boring’s photographer in Iraq, I’ve been in and out of the area surrounding Jalawla for several weeks. My reporting should make one thing clear. The battle for this symbolic town is emblematic. The war on Islamic State could grind on … for a long time.

The office of Gen. Hussein Mansoor—the head of the PUK Peshmerga in Khanaqin, the Kurds’ main base near Jalawla—is a lot busier than usual.

So my translator makes a call and we head around town to a base previously belonging to KDP Peshmerga. When we visited this base before, there was just one guard with a Kalashnikov. This time there are Pesh fighterseverywhere.

One of them leads us into a palatial building that appears to once have been someone’s home. A very rich someone. There’s a huge reception room teeming with senior PUK officials—some in uniform, others wearing civilians clothes.

We sit down and exchange small talk before an unassuming man walks in wearing traditional dress. As we shake hands, someone introduces him as Gen. Mahmood Sangari, the sector commander responsible for 150 kilometers of the front line including Jalawla.

Sangari tells us that for now the Peshmerga are helping the Iraqi army, in the interest of protecting Kurdish land. “The Iraqi army would attack us if Islamic State were not in Mosul,” he says.

The general admits that, in terms of supplies, his fighters have received only two heavy machine guns and some Katyusha rockets. And he’s not even sure who sent them. “We need everything we can get. We are still waiting for more weapons to arrive.”

He says his soldiers haven’t received any help from the Americans … yet. “We see the U.S. saying they will help on TV,” he complains. “This is the war on terror, they should help, but we don’t see anything.”

Sangari says that Islamic State has every intention of infiltrating Turkey and Yemen and other Muslim countries. “They want to be responsible for all Islamic areas,” he says. “The plan then is to make a jihad against Europe. I think if the Peshmerga were not here, ISIS could do everything they want.”

But for him, this fight is deeply personal. “We have to attack and take back our land,” the general proclaims. “We want a historic Kurdistan. Our land.”

Peshmerga gear up for the front line. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

Peshmerga gear up for the front line. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

We ask about seeing the front line. The generals talk among themselves. The line is dangerous at this time of day, they say. Militant activity increases in the evening. Sangari suggests returning in the morning when it will be safer.

But then one of his officers, Brig. Gen. Salmad Beertwata, offers to take us to a different part of the line. Pesh fighters usher us toward a Toyota pickup truck. Six fighters pile into the back of the truck—depicted above—and we’re on our way.

“People think we have a good relationship with Israel, but I think that it’s just talk,” Beertwata says as he drives. “We have heard that there are American soldiers [in Kurdistan]. We have not seen them. This is the front line. Where are they?”

Refugee camp and kite. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

Refugee camp and kite. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

We pass a school. There’s a camp outside for refugees from Jalawla. Farther down the road again another camp has sprung up. A kite flies over the camp — some child trying to entertain himself.

We drive through some villages on the way out of Khanaqin. Beertwata says they are mostly Shia Arab communities with some Kurds.

We arrive at a Peshmerga position along a ridge. We can see other positions on either side of us sporting heavy machine guns—plus one recoilless rifle on a pickup truck. All aimed at Jalawla in the distance.

Jalawla, as seen from Kurdish lines. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

Jalawla, as seen from Kurdish lines. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

As we exit the vehicle, a portly Peshmerga soldier comes up to me, shakes my hand and asks, “Chonee beshee kaka?” He kisses me on the cheek in the way that the Kurds greet a friend. It dawns on me that I’ve met this guy before.

He’s a 37-year-old veteran named Alwat with whom I swapped stories of military life while we were both in Khanaqin during a previous visit.

He smiles broadly and clasps my hand. Even though he speaks just 10 words of English and my Kurdish vocabulary is not much better, we manage to communicate that we’re both doing well. All things considered.

Kurdish lines outside of Jalawla. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

Kurdish lines outside of Jalawla. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

The positions here are a far cry from those the Peshmerga maintained when they were operating in Jalawla itself. While fighting in the city, they lived in civilian houses and government buildings.

On the ridge, a Kurdish platoon lives out in the open, exposed to the burning sun. This part of Iraq—Garmian province—literally takes its name from the Kurdish word for “hot.”

Peshmerga fighters outside Jalawla. Matt Cetti-Roberts photos

Peshmerga fighters outside Jalawla. Matt Cetti-Roberts photos

There are wisps of smoke in the distance. Beertwata tells us that the previous night, the Peshmerga fought a three-hour battle with militants. Something’s still burning.

As we make our way back to Khanaqin, Beertwata stops to talk to a group of armed men dressed in traditional Kurdish suits standing by the side of the road. Most of them carry Russian Dragunov sniper rifles.

“The guys heading to the front line are volunteers,” Beertwata says. “They want to help the Peshmerga.”

“They enjoy fighting,” he adds. Beertwata explains that the volunteers will wait for dark and then try to pick off militants in Jalawla.

Returning to Khanaqin. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

Returning to Khanaqin. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

As we continue driving, Beertwata expresses his puzzlement at volunteers who’ve come to fight for the other side. “I find it hard to understand why Muslims from Europe would join ISIS,” he says. “They have such a good standard of life there, but they still come.”

Six days later, the Peshmerga say it’s too dangerous to go to the front line. Instead, they take us to talk to Aras Talabani, a nephew of PUK party founder and former Iraqi vice president Jalal Talabani.

“Today’s operation went well,” Talabani says. “All of the areas around Sadia and Jalawla are under Peshmerga control.” He says the PUK Peshmerga conducted the operation with elements of Asayish intelligence and a detachment from the elite Kurdish Counter Terrorism Group.

“We have no communications with the Iranians,” Talabani says, flatly denying reports of Iranian involvement in the battle. Both War Is Boring’sJassem Al Salami and Al Jazeera have reported Iranian troops crossing into the area near Jalawla.

A Peshmerga sentry near Khanaqin. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

A Peshmerga sentry near Khanaqin. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

Moreover, the Peshmerga near Jalawla haven’t benefited from American air strikes like the Peshmerga in the west have. “The U.S. does not help in this area,” Talabani says. “Maybe because we do not have any Christians here.”

But he says the Iraqi military is providing air support. The Peshmerga have set up an operations room where they can talk directly with Baghdad.

“We now have a good relationship with the Iraqi army,” Talabani says. “The Iraqi army has helped us with artillery and air support.” He mentions the Iraqis sending Sukhoi warplanes. “Though the Sukhois were too late to fight today.”

He tells War Is Boring that he frequently flies to Baghdad for meetings with Iraqi leaders. “I have Sunni friends. They do not like ISIS. They say the new Iraqi prime minister is better than Maliki.” But he admits that the Sunnis are waiting for the government to prove its willingness to support thembefore they start fighting Islamic State.

Talabani says the KDP Peshmerga who were in Khanaqin and Jalawla left two weeks ago. Now the PUK is all alone.

“Three Peshmerga died today,” he says. “One by a sniper and two from an IED left by ISIS fighters. Many bombs were left behind.”

Talabani insists the PUK in Khanaqin haven’t received any of the the supplies the West has pledged. “Maybe the weapons that have been sent by other countries go to the KDP Peshmerga—I do not know,” he says.

Even with minimal help, he says he’s pleased with the progress the Peshmerga have made. The Pesh control the roads between Jalawla and Sadia. “With most of Jalawla and Sadia surrounded, there is only a small corridor for [militants] to leave,” he explains.

“We’re in no hurry to take Jalawla,” Talabani says. “We just want to control and open the roads. ISIS can go nowhere.”

Traffic between Baghdad and Kurdistan. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

Traffic between Baghdad and Kurdistan. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

“The Peshmerga still do not have Jalawla, but we are close,” a Kurdish intelligence officer tells us.

We’re at the Zarow checkpoint, not far from Khanaqin. The checkpoint overseas a road that runs along a corridor close to the Iranian border. A lone Iraqi army soldier joins the Peshmerga who normally man at the checkpoint.

Traffic passes through en route to Baghdad and the rest of Iraq. Some of the trucks are going as far south as Basra. It’s one of the few direct links left between north and south.

The guards say there was recently fighting close to the checkpoint, but that it has died down. They tell us that they can now call in Iraqi air support.

Sherko Merwis is head of the PUK party in Khanaqin. “We didn’t take Jalawla, but we control access to these areas,” Merwis says. “Informants say that conditions for ISIS [in the towns] are very bad.”

He explains that the militants want to draw the Peshmerga into bloody street-by-street fighting—bait the Pesh have ignored. He claims that roadside bombs have accounted for all the Peshmerga who have been killed or injured in recent operations.

“The plan now is to get rid of ISIS from the district slowly,” he says. “We do not want to lose lots of Peshmerga. We want to control the roads.”

There have been reports that Kurdish PKK militia, which many countries label a terrorist group, have gotten involved in the fighting, but Merwis denies it. “The PKK want to come, but we do not allow them. We told them that, ‘We are strong here. We don’t need you.’”

He says that there are only militants left in Jalawla. All 82,000 residents have fled, he claims. “Because of this we are free to use heavy weapons.”

Merwis says the PUK considers local Arabs—the ones who have lived herebefore the Arabization of the region—to be friends. “We defend all. We do not have two levels of people.”

But that doesn’t mean that everyone is neighborly here in Khanaqin. “The other Arabs, Saddam brought them,” Merwis explains. “They took Kurdish houses. We will get rid of them.”

In particular he cites the Karway tribe. He says around 100 members of the tribe are fighting for Islamic State.

Relic left by U.S. Army troops that once manned Zarow checkpoint. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

Relic left by U.S. Army troops that once manned Zarow checkpoint. Matt Cetti-Roberts photo

But the 10,000-strong tribe’s members appear to be divided in their loyalties. Perhaps in a bid to curry favor with the Kurds, some are helping the Pesh track down fighters.

The situation is complicated. Merwis admits there are even Kurdish jihadists among the militants.

Nearby, Mullah Bakhtiar—a member of the PUK politburo who lives just outside Khanaqin—is entertaining guests. “[The battle is important] because it is near Khanaqin,” Bakhtiar says. “If ISIS came, it would be like Sinjar.”

In early August, Islamic State surrounded tens of thousands of minority Yezidi refugees on the mountain, compelling the U.S. and other countries to intervene with air strikes. “There are many minorities,” the politician says of Khanaqin. “ISIS would kill them all.”

He mentions that regular PUK members would also be targets because militants consider all members of the Socialist PUK to be atheists. But many PUK members are, in fact, practicing Muslims.

“This type of terrorist has a very different type of ideology,” Bakhtiar tells us. “Some of them believe that they will go to paradise if they die fighting. Fighting these kinds of people is difficult in the beginning, but step-by-step we learn.”

Like many Kurdish leaders, he bemoans the slow trickle of supplies. “Some of the weapons are getting to the PUK, but none of them were here in time for our battle,” he says.

The current conflict has united many disparate Kurdish factions. He praises the PKK for aiding the PUK in Kirkuk, helping the Yezidi at Sinjar and participating in operations in Makhmur. But he’s less kind in his appraisal of the ruling KDP.

“KDP and PUK have different ways of fighting ISIS. In the start, yes, the PUK expected problems. The KDP did not. Before Mosul we thought that ISIS would attack, but no one listened.”

He says he believes the fall of Sinjar and Hamdaniya, which were underKDP protection, has weakened the KDP’s standing. “Especially amongst the Yezidi, but also all of the people around Kurdistan,” he says. “The PKK is stronger in Sinjar after what happened there.”

Despite the Kurds’ cooperation with Iraqi forces, Bakhtiar says nothing has changed between the Kurdistan and Baghdad. “Kurdistan being free has no relation with ISIS. This is something for the people. Any time we feel we want to leave, we will.”

“But we must have an agreement that the disputed areas may have a referendum [on joining the KRG or staying with Iraq proper],” Bakhtiar adds. “If they do it, it is good. If not, it is very bad, because it is our right.”

Peshmerga guards at Zarow checkpoint. Matt Cetti-Robert photo

Peshmerga guards at Zarow checkpoint. Matt Cetti-Robert photo

A medical delegation from the KRG health ministry is also visiting with Bakhtiar. A senior member of the delegation tells War is Boring that 35 Peshmerga were wounded in the fighting.

“The injured go to hospitals like Khanaqin and Kalar for treatment,” the delegate explains. “If more treatment is needed, they go to the hospital in Sulaymaniyah.”

Many communities around Khanaqin, like Bahari Taza, have taken in refugees fleeing fighting in the west. The fall of Jalawla has added to the strain. “There are also many [displaced people] from the towns, as well as the Syrian refugees,” the medical official says. “We should be getting supplies from Baghdad, but because of the roads and the conflict, they are reduced.”

“Sometimes the Iraqi army and Shia militia do not let supplies through, not always for any reason that we know,” he says. “When they get stopped, the Peshmerga have to make calls to get them released.”

The delegate tells us the KRG is unable to fully manage the refugees. So far they’ve had no serious problems with disease. But he says Mosul is an area with a high occurrence of measles. With so many refugees from Mosul now in Kurdistan, there’s worry of an epidemic. He says the health ministry is trying to prevent disease outbreaks.

No comments:

Post a Comment