When American military aircraft attacked Islamic State militants in Syria on the night of Sept. 23, they carried special missiles designed to destroy air-defense radars.

Official military videos and photos depict U.S. Air Force F-16 and Navy EA-6B jets with the High-Speed Anti-Radation Missiles, or HARMs, under their wings.

The images are indicative of the Pentagon’s worry over Syria’s air defenses. Although U.S. forces are not attacking the regime of Syrian president Bashar Al Assad—and in fact are targeting Al Assad’s Islamist foes—American commanders are apparently worried that regime troops might try to shoot down U.S. and allied warplanes.

And for good reason. Washington has announced it will train and equip thousands of moderate rebel fighters in Syria in a bid to bring an end to the three-year-old Syrian civil war. The moderate rebels are currently battling Islamic Stateand the regime.

And for good reason. Washington has announced it will train and equip thousands of moderate rebel fighters in Syria in a bid to bring an end to the three-year-old Syrian civil war. The moderate rebels are currently battling Islamic Stateand the regime.

As it happened, regime radars—and the surface-to-air missiles they guide—remained inactive on the first night of American-led air strikes. “The target acquisition last night, radar acquisition on the part of Syria I would characterize as passive,” Army Lt. Gen. William Mayville, Pentagon director of operations, said on Sept. 23.

But as they plotted the air raids, planners didn’t know that would be the case. They prepared for the worst. Not only did F-16s and EA-6B planes carry HARMs—in case the regime activated its air defenses and the Americans needed to shoot back with radar-homing munitions—commanders also assigned the most dangerous targets to high-tech F-22 stealth fighters and cruise missiles.

Some time prior to the first wave of attacks, U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Samantha Power notified her Syrian counterparts that the air raids were coming. Not notifying the regime would have been a violation of Syria’s sovereignty.

But that doesn’t mean that U.S. and Syrian military officials worked together. “There was no coordination, no communication with the Assad regime,” said Rear Adm. John Kirby, the Pentagon’s top spokesman.

So U.S. Central Command’s air planners—working around the clock in a high-tech command center in Qatar—assumed the worst. They were prepared for the regime to fight back.

Syria’s own jet fighters posed some threat. But years of warfare have sapped the regime’s air force of its strength. Crashes and rebel guns and missiles have claimed around 100 of Damascus’ planes and helicopters. The air force’s main jets—45 MiG-21s, 35 MiG-23s and 25 Su-22s—are in “urgent need of overhaul,” according to Tom Cooper, writing in Combat Aircraft.

Arguably the greatest threat was from the ground. Before the civil war began in 2011, Syria possessed a fearsome integrated air-defense network with tens of long-range radars and scores of missile emplacements.

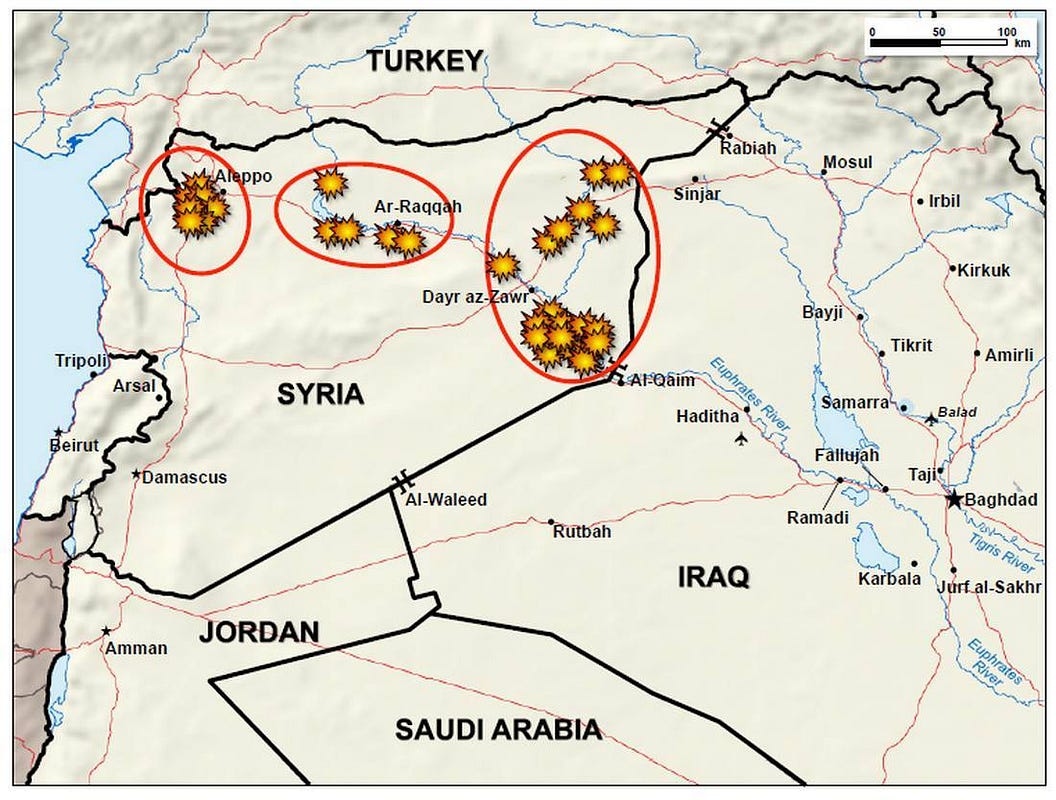

The defenses concentrated in Syria’s western heartland. Overlapping short- and long-range missiles covered the northern city of Aleppo, and some Western-based S-200 missiles even possessed the range to hit planes over the north-central city of Ar Raqqa, Islamic State’s “capital.” A few outlying missile systems defended Dayr Az Zawr in the east.

By 2014, the Dayr Az Zawr defenses were fully in Islamic State’s hands, but appeared to be non-functional. The Islamists shot down their first regime warplane on Sept. 16 … with gunfire, not missiles.

At left—the locations of the Sept. 23 strikes. U.S. Defense Department art. At right—the coverage of Syria’s air defenses in 2010. Air Power Australia/Google Earth art

At left—the locations of the Sept. 23 strikes. U.S. Defense Department art. At right—the coverage of Syria’s air defenses in 2010. Air Power Australia/Google Earth art

No, the main threat appeared to be regime air defenses. Especially considering the compelling evidence that the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps has deployed into Syria to help the regime repair and upgrade its radars and missiles.

“Against a limited incursion, the Syrian air-defense network remains capable, despite the reliance on aging Soviet-era systems,” Air Power Australia’s Sean O’Connor concluded in 2010.

Central Command wanted to hit three clusters of targets on Sept. 23, Kirby explained—Islamic State facilities, supply depots and vehicles in Dayr Az Zawr and Ar Raqqa, plus a band of former Al Qaeda terrorists in Aleppo known as the Khorasan Group.

Roughly speaking, the farther west the targets were in Syria, the more dangerous they were for U.S. and allied planes. And that assumption helps explain how Central Command organized the initial air strikes.

“Last night’s strikes were organized in three waves,” Mayville said on Sept. 23. The first wave, commencing at midnight local time, was composed of Tomahawk cruise missiles. The Navy destroyer USS Arleigh Burke and cruiser USS Philippine Sea fired more than 40 of the low-flying cruise missiles.

At least one Tomahawk struck an Islamic State building in Ar Raqqa, but most of the missiles continued deeper into Syria, where the regime’s air defenses are densest. With no crew aboard, a Tomahawk is expendable. It’s for that reason that the U.S. military often begins an air campaign by firing cruise missiles at the toughest targets.

The Tomahawks struck the Khorasan Group’s camps.

An EA-6B returns to USS George H.W. Bush on Sept. 23 with its HARM still underwing. Navy photo

An EA-6B returns to USS George H.W. Bush on Sept. 23 with its HARM still underwing. Navy photo

The second wave, shortly after midnight, included U.S. and Emirati F-16s plus American F-15s, B-1 bombers and drones. These aircraft struck targets in Ar Raqqa and Dayr Az Zawr, farther from the most dangerous concentrations of regime defenses. But some of these F-16s were apparently hauling HARMs, just in case.

It’s worth noting that Predator drones had been flying over Ar Raqqa in broad daylight since at least Sept. 6, presumably scouting out targets for the Sept. 23 raids. That a slow-flying drone could safely reconnoiter the city during daytime testifies to Islamic State’s inability to shoot back against aircraft over its own capital.

But regime air defenses including S-200 missiles might have covered areas on the westernmost edge of the second wave’s zone, including Islamic State facilities near the strategic Tishrin Dam. So it’s no wonder that Central Command sent the Air Force’s speedy, radar-evading F-22s to hit these targets with 1,000-pound GPS-guided bombs.

Along with the B-2, the F-22 is one of the flying branch’s most survivable warplanes. The attacks around Tishrin Dam represented the F-22’s combat debut, nine years after the pricey stealth jet entered service.

What’s curious about the F-22 bombing runs is that something—another plane or a drone, apparently—recorded the bomb blasts on video. Aviation Week reporter Bill Sweetman speculated that the accompanying surveillance craft was “most likely an unmanned air vehicle.”

“How come it didn’t get shot down, if the air threat called for a supersonic stealth fighter?” Sweetman wondered.

One possible explanation is that the drone was also stealthy. Not coincidentally, the Air Force has been known to operate RQ-170 radar-evading drones from the Al Dhafra in the United Arab Emirates, the same base the F-22s call home when they’re in the Middle East.

The third wave of air raids launched around 3:00 in the morning, local time, and included Navy and Marine jets flying from the carrier USS George H.W. Bush and the assault ship USS Bataan, plus aircraft from allied Arab air forces. The UAE, Bahrain, Jordan and Saudi Arabia have all sent planes—including F-16s and Tornadoes—to join the Americans.

The Navy’s wave presumably included the EA-6Bs with their radar-killing HARMs.

For the most dangerous raids in western Syria, Central Command sent cruise missiles. For slightly less dangerous attacks farther east, it sortied F-22s. F-16s and EA-6Bs with anti-radiation missiles accompanied warplanes striking the least dangerous targets on Syria’s eastern frontier.

In short, no U.S. or allied attackers struck Syria without being expendable, fully stealthy or escorted by specialized radar-hunters.

The caution proved unnecessary. The regime didn’t open fire. All attacking jets returned safely to base. An official photo depicts an EA-6B landing onBush still cradling its HARM missile underwing.

No comments:

Post a Comment