Everything about this nuclear war test tower was extraordinary

For more than 40 years, the BREN Tower at the U.S. government’s atomic warfare playground in Nevada held the record as the tallest free-standing structure west of the Mississippi River.

Its 1,527-foot height topped the Eiffel Tower and the Empire State Building. Few structures—among them North Dakota’s KVLY-TV Mast, New York’s World Trade Center, Chicago’s Sears Tower and Toronto’s CN Tower—stood taller on North America’s soil.

The BREN Tower’s stature was the result of an unusual requirement. Its height equaled the detonation altitude of Little Boy—the first nuclear weapon—when it exploded above downtown Hiroshima.

The tower allowed American and Japanese scientists to precisely simulate the radiation exposure of thousands of atom bomb survivors.

Although scientists scrutinized the aftermath of the Little Boy and Fat Man bombs, wartime circumstances and catastrophic damage left many uncertainties about the effects of radiation on the people exposed to the bombings.

Twenty years after the explosion, the U.S. government set out on a major experiment to carefully measure the dosages Hiroshima victims received from the blast. In 1962, scientists from the Atomic Energy Commission with assistance from Japan began a multi-year study of Hiroshima radiation exposure at the Nevada Test Site.

To assist the experiment, the Oak Ridge National Laboratory developed a small, unshielded nuclear reactor which NTS engineers mounted atop the huge spindly tower.

The experiment’s title gave the tower its name—Bare Reactor Experiment-Nevada, or BREN.

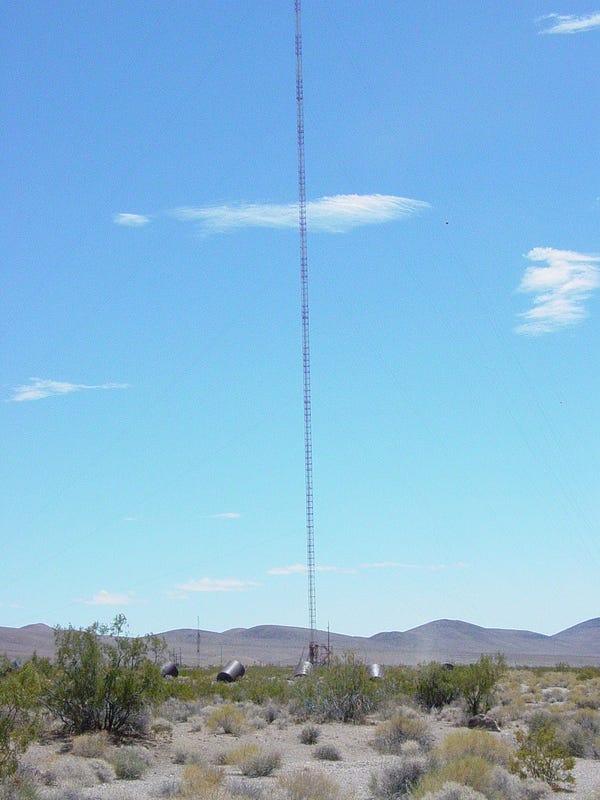

The BREN Tower. Department of Energy photo(Tower of radiation)

For the experiment to work, the design had to resemble a close approximation to the real attack. At the tower’s base, workers constructed a number of Japanese-style buildings using materials identical to those used in Hiroshima structures.

Next, to simulate the effects of radiation on human bodies, researchers interviewed bomb survivors about where they were standing when the atomic bombs hit. The scientists then placed mannequins outfitted with sensors at a similar distance to where the survivors stood.

With the BREN reactor beaming out radiation and contaminating the surrounding buildings and mannequins, the scientists collected precise exposure data unavailable in the days and years after the explosion.

True, the experiment was a bit morbid, but the data helped scientists on both sides of the Pacific better understand the long-term health effects of nuclear weapons. Studies of the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki continue to this day—even as those exposed to the bombs’ effects reach the end of their lives.

When the BREN experiments ended in 1966, crews disassembled the tower and moved it several miles—from Yucca Flat to Jackass Flats. They also swapped out the exposed reactor with a small, linear particle accelerator for further radiation tests.

During some of these later tests, the M-1 Abrams tank and other armored vehicles matched their protective capabilities against the heavy shine streaming from the BREN Tower’s top.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Federal Aviation Administration employed BREN’s unique combination of tremendous height and remote location to determine the legal noise limits for American airports.

The FAA used batteries of microphones for these tests. Positioned at various elevations above the desert floor, the microphones recorded noise levels from every commercial aircraft flying American skies.

The tower’s great height allowed its microphones to capture data from an aircraft flying 1,000 feet above the desert. The FAA then used the data to craft noise regulations.

By the 21st century, scientists exhausted the research uses of the BREN Tower. It sat idle. But it wasn’t cheap. It cost $50,000 a year to maintain the giant structure, along with its supporting cables and elevator.

A routine inspection revealed needed repairs that would have cost more than a million dollars to fix. In 2012, the tower’s 50-year history ended with a bang in one of the tallest structure demolitions ever.

Zany experiments

Jack Doyle, who worked on BREN Tower experiments with the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and who supplied material for this article, recalled one idea for an experiment that never happened.

The reason? It was too wacky. It might even be one of the wackiest tales ever told about the Nevada Test Site.

A lot of development work on the Peacekeeper intercontinental ballistic missile took place at the NTS. In addition to underground warhead and re-entry vehicle tests, engineers explored how to store and harden missile silos above and below the desert soil.

The Peacekeeper program produced some truly blue-sky basing concepts, ranging from underground race tracks to giant hovercraft.

None of these projects saw much further development, but one question seemed serious enough to require a real test.

What would happen to hardened missile silos during a Soviet or Chinese nuclear first strike? Nuclear detonations kick up vast quantities of rock and dirt—would these jam the heavy silo hatches shut and entomb the Peacekeepers?

Doyle said that weaponeers discussed raising a large, heavy object they dubbed the “BFR” to the top of the BREN Tower. You can guess what the acronym stands for. Then, they would drop it onto a sample silo hatch more than 1,500 feet below. Instruments and eyeballs would determine if the hatch survived—and functioned properly—after the impact.

Basic physics killed this zany idea. “No one could figure out a way of lifting the BFR to the top of the tower without the tower shaking itself to pieces,” Doyle told War is Boring.

Presumably the weaponeers found other methods of answering their questions, for the BFR experiment never added to the BREN Tower’s many achievements.

You can follow Steve Weintz on Twitter at @Moe_Delaun. Sign up for a daily War is Boring email update here. Subscribe to WIB’s RSS feed here and follow the main page here.

No comments:

Post a Comment