Robert Farley

23 Jul 2014

Efforts to abolish the U.S. Air Force seem to come around every 30 years or so

My new book Grounded isn’t the first proposal aimed at totally doing away with the U.S. Air Force.

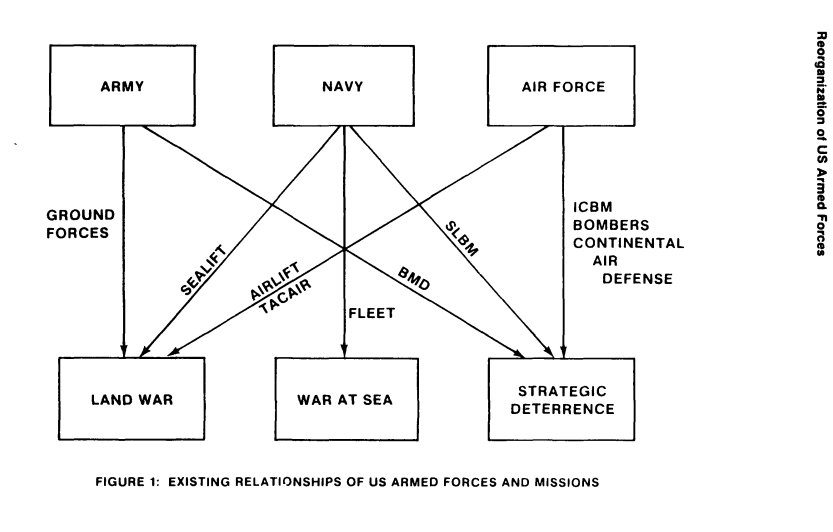

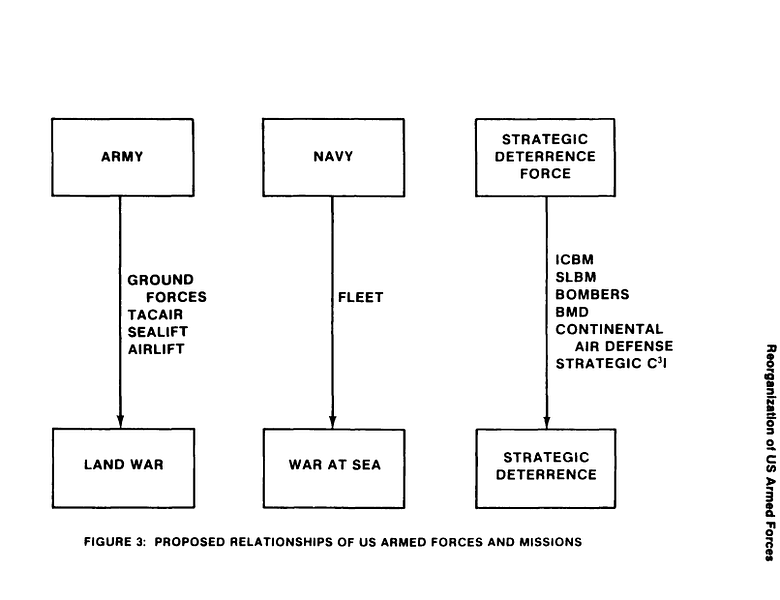

In 1982 John Byron—then a Navy commander and submarine skipper—argued that the United States should reorganize its military around three branches, eliminating the Air Force and creating a new Strategic Deterrent Force.

“Reorganization of the U.S. Armed Forces” was the first strategic study co-published by the National War College and the National Defense University Press. It made the rounds among defense analysts at the time. It attracted some attention from the defense reform community and an audience in some of the professional defense journals, including Proceedingsand Early Bird, the much-beloved Pentagon news roundup that ceased publication in 2013.

Byron, a graduate of the University of Washington, argued for dividing the services into an army, a navy and a deterrence force that would encompass the Navy and Air Force’s nuclear missions.

He detailed the problems that mission-overlap created between the services and argued that inter-service divisions inevitably resulted in conflict. Byron used a memorable musical metaphor—one that I wish I’d stolen—to describe the problems of Army-Air Force collaboration.

“What I see is two drummers, two drums and two entirely different rhythms,” he wrote. “The organizations occasionally exchange sheet music or sometimes rehearse together, but the melodies—the doctrine and training and tactics—are service-specific.”

“What I see is two drummers, two drums and two entirely different rhythms,” he wrote. “The organizations occasionally exchange sheet music or sometimes rehearse together, but the melodies—the doctrine and training and tactics—are service-specific.”

Now retired, Byron made time to chat with me about his proposal via e-mail. He detailed some of the key points and explained how the debate played out in the 1980s.

The plan’s most attention-grabbing element was the call to eliminate the Air Force. Byron told me he had little use for strategic bombing, pointing out that the ability of manned bombers to penetrate advanced air defense had declined dramatically since World War II—and that missiles had become a considerably more reliable means of delivering nuclear warheads.

Byron said that while the Army was glad to see the Air Force go in 1947, it would welcome its return today—and that this would lead to an organization more capable of balancing the contributions of different systems and branches.

The call for abolishing the Air Force was particularly interesting given that Air Force general Perry Smith, author of The Air Force Plans for Peace 1943-45, provided the foreword for Byron’s monograph. Smith’s book was extremely critical of the interwar Army Air Corps, as well as the Army Air Forces in World War II.

Another interesting element involved dividing the submarine fleet between two services. The attack submarines would remain with the Navy, while the ballistic missile boats would shift to the new Strategic Deterrent Force.

In our conversation, Byron suggested that responsibility for design, construction and manning would remain with the Navy, with the SDF controlling operational deployment. The tactical tasks of attack boat and boomer officers were sufficiently distinct that it was pointless keeping them in the same community.

In our conversation, Byron suggested that responsibility for design, construction and manning would remain with the Navy, with the SDF controlling operational deployment. The tactical tasks of attack boat and boomer officers were sufficiently distinct that it was pointless keeping them in the same community.

Byron’s proposal came at what many believe was the modern nadir of inter-service relations. Service competition and parochialism had proven extremely damaging in the disastrous Operation Eagle Claw hostage-rescue in 1980, and again during the 1982 invasion of Grenada.

In part spurred by these perceived failures, the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986 sought to remedy many of the problems Byron identified. The law shifted more authority for planning and organization to the Pentagon’s regional combatant commanders, while leaving procurement in the hands of the services.

The act also provided resources for study of “joint” warfighting issues and created better career paths for officers to pursue “jointness.”

Also the Army’s development of AirLand Battle doctrine, to which the Air Force largely acceded, helped remedy many of the inter-service concerns. Neo-classical strategic bombing theory, as espoused by John Warden among others, was still a decade away.

Byron granted that Goldwater-Nichols helped, but argued that it didn’t and couldn’t solve the basic resource conflict issues that stem from overlapping missions. The retired submarine captain blamed inadequate Army-Air Force cooperation for the military’s failure to capture Osama Bin Laden at Tora Bora in 2001.

Byron maintained his pro-reform stance, focusing on the distinction between smart platforms and smart weapons. “None of the services has done an adequate job of taking full advantage of smart weapons, at least as far as dialing back its insistence on smart platforms, too,” he told me.

Because the services tend to be platform-oriented—devoting most of their cash and energy in building new ships, planes and tanks—they do a poor job evaluating the trade-offs between platforms and weapons. Sometimes a better missile is more useful than a better ship, for instance. Older ships could carry the new munition, potentially offering useful new capabilities at modest cost.

But Byron said he’s skeptical of the prospects for a major reorganization. “The Iron Triangle flat would not allow it,” Byron claimed in a follow-up letter he wrote a couple years after his initial study. “It would make the services’ heads hurt so much that … the idea would make them collectively catatonic.”

Still, arguments like Byron’s—and hopefully mine in Grounded—serve as a foundation for big, complex evaluation of the contributions that the military branches make to American security.

Reform proposals face overwhelming headwinds in the form of organizational inertia and entrenched interest. It’s never out of line to remind people that the organizations we have are the ones we made, and that we can remake them when we decide we really want to.

Sign up for a daily War is Boring email update here. Subscribe to WIB’s RSS feedhere and follow the main page here.

No comments:

Post a Comment