Scene from the 1950 Chinese film ‘The Girl With the White Hair.’ Changchun Film Studio capture

Maoist tactics, organization and philosophies influenced the U.S. Marines

Kevin Knodell in War is Boring

We’ve all heard the phrase “gung ho.” Today we associate the phrase with enthusiasm, sometimes perhaps over-enthusiasm. Fittingly, it entered the American lexicon as a Marine Corps battle cry.

But the Marines didn’t come up with it on their own. It comes from the Chinese gōng hé, roughly meaning “work together.”

Not only that, a Marine commander picked it up in China while observing Maoist troops fighting against Japan. From there, the commander popularized the term while leading Marine raiders during the Pacific war.

There’s an old story that the Marines adopted the expression while stationed in China in the early 20th century. As the story goes, the Chinese were so impressed with the Marines, they started calling them gōng hé for their outstanding teamwork.

But that story isn’t true. In fact, gōng hé was a Chinese communist work slogan. Nor was the phrase the only hint of Maoism to influence the Marines. To this day, Marine tactics remain subtly influenced by Chinese communist guerrillas.

But that story isn’t true. In fact, gōng hé was a Chinese communist work slogan. Nor was the phrase the only hint of Maoism to influence the Marines. To this day, Marine tactics remain subtly influenced by Chinese communist guerrillas.

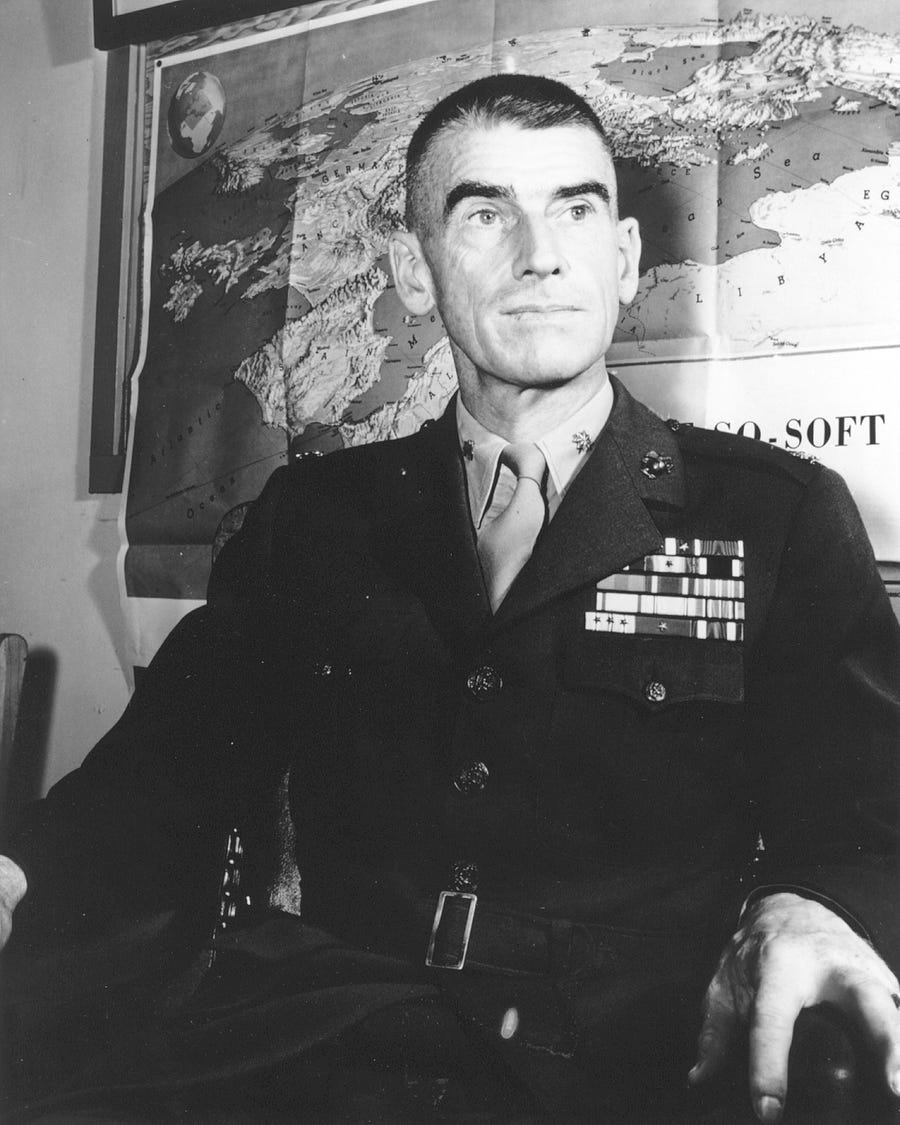

Evans Carlson as a brigadier general. Marine Corps photo

Carlson in China

The term “gung ho” owes its popularity in the West to a man named Evans Carlson.

Carlson had a colorful military career, joining the Army and serving as an enlisted man in The Philippines and Hawaii. He left as a sergeant, then re-enlisted in time to serve during the Punitive Expedition in Mexico prior to the American entry in World War I. After that, he served as an officer in Europe.

After the war, Carlson left and enlisted in the Marines, starting over as a private. Once again, he worked his way up to an officer’s commission. He served multiple tours of duty in South America and China.

But it was his tour of China as a military observer in 1937—and his study of the Chinese language—that would influence the Marines and American popular culture. He accompanied Chinese nationalist troops into battle and watched Japanese forces in action. While in China, he met American journalist Edgar Snow, author of the sympathetic book about communist guerrillas, Red Star Over China.

Carlson was intrigued by these guerrillas—still little known to the rest of the world—and decided to see these fighters for himself.

He made his way to the communist headquarters in the north. He met Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, observed guerrilla operations and often accompanied the rebels on foot or horseback. He was impressed by the guerrillas tenacity and their ability to improvise and maintain high morale in the face of deprivation.

He also struck up a fast friendship with Rewi Alley, a leftist from New Zealand who joined up with the communists. Alley also helped set up a system of work collectives—known as the Chinese Industrial Cooperatives—to support the fight against Japan.

Gōng hé was their slogan. Carlson started using it himself.

Upon his return from China, he became outspoken about what he saw as the threat of Japanese aggression … and heaped criticism of the sale of American materials being used to supply Tokyo’s war effort. This was unpopular with his commanding officers, who told him to be quiet. Carlson resigned his commission and began writing about the Japanese threat while lobbying for an embargo.

Marine raiders in the Pacific during World War II. U.S. National Archives photo

Marine raiders in the Pacific during World War II. U.S. National Archives photo

Carlson’s Raiders

As tensions between Japan and the United States escalated, Carlson rejoined the Marines.

His direct knowledge of Japanese tactics, as well as his friendship with Pres. Franklin Roosevelt’s son Capt. James Roosevelt, led him to be fast tracked into a special assignment. He was now in command of the Second Marine Raider Battalion, a special commando unit, with Roosevelt as his second-in-command.

Carlson’s leadership of the battalion was unconventional and rattled many of his fellow officers.

For one, he fundamentally changed the structure of rifle squads, ignoring the traditional eight-Marines-per-squad allotment. Instead, Carlson modeled his battalion on the Chinese guerrillas. He organized 10-man squads each with one squad leader and three fire teams of three Marines apiece.

More galling to his colleagues were the philosophies he introduced to the battalion, and his practice of “ethical indoctrination.” Having served as both an enlisted man and an officer, Carlson despised the notion of officers as elites whose orders were to be religiously obeyed.

Once again he took pages out of the guerrilla handbook. He emphasized the role of non-commissioned officers, encouraging inexperienced officers to seek their mentorship and to think of their own positions as primarily a position of responsibility, rather than power.

He built strong espirit de corps in the unit. Gōng hé—gung ho—became their slogan and battle cry.

Under Carlson’s leadership, the Raiders undertook the famous Makin Island raid—one of the first U.S. offensive actions in the war. They also conducted a long campaign against the Japanese on Guadalcanal known as “Carlson’s Patrol,” in which Marines and local scouts under Carlson’s command used hit-and-run tactics to harass and confuse the Japanese. In 29 days the Raiders killed around 500 Japanese troops at a cost of only 16 of their own.

After Guadalcanal, the Marines reorganized the commando units under the 1st Raider Regiment. Carlson became the regiment’s executive officer. Lt. Col. Alan Shapley commanded the 2nd Raider Battalion.

Shapley had a much more conventional mindset. He reorganized the battalion to be more in-line with other Marine units. He did however, maintain Carlson’s squad structure of three fire teams. Soon, the entire Marine Corps would adopt this standard.

Carlson came down with malaria, forcing him to temporary retire to the United States for treatment. While recovering, he served as the technical adviser for Gung Ho!: The Story of Carlson’s Makin Island Raiders, a fictionalized war propaganda film based on the exploits of his raiders.

The film was a hit, and introduced the America public to the phrase “gung ho.” The phrase started becoming widely used by servicemen and civilians alike.

“I was trying to build up the same sort of working spirit I had seen in China, where all the soldiers dedicated themselves to one idea and worked together to put that idea over,” Carlson told Life magazine in a 1943 interview. “I told the boys about it again and again. I told them of the motto of the Chinese Cooperatives, gung ho. It means work together—work in harmony.”

Carlson was not content to sit at home talking about his Marines. He wanted to be back in the Pacific leading them. Upon his return, he participated in the battles for Tarawa and Saipan. In Saipan, he was wounded while attempting to rescue an injured marine radio operator.

He retired as a brigadier general in 1946. He died of a heart condition less than a year later. He missed out on the McCarthy hearings.

Had he lived, there’s a chance America’s post-war anti-communist witchhunt would have ensnared Carlson. His left-wing tendencies had never been a secret in the Corps, traditionally a bastion of conservatism. But the Marines overlooked it. Fellow marine and future commandant of the Marine Corps David Shoup’s appraisal of Carlson was that “he may be red, but he’s not yellow.”

Just a few years later, Marines would shout “gung ho!” as they went into battle against Chinese forces in Korea. They fought a bitter war against the very men whose tactics transformed the Corps.

The Marine Corps still uses Carlson’s squad structure—although with an additional man for each fire team. And “gung ho” still means aggression and enthusiasm.

You can follow Kevin Knodell on twitter at @KJKnodell. Sign up for a daily War is Boring email update here. Subscribe to WIB’s RSS feed here and follow the main page here.

No comments:

Post a Comment