Alan Weisman in Matter

How Iran’s explosive expansion warns us about our overpopulated future —and shows us how to fix it.

i. Horses

WHEN HOURIEH SHAMSHIRI MILANI entered medical school in 1974, just thirteen of seventy students in her class at the National University of Iran were women. “And of those thirteen, only two of us wore the scarf.”

During the reign of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, the final Shah of Iran, head covering was rare among educated women. In 1936, seeking to modernize the country, his father, Reza Shah Pahlavi, had decreed that all Iranian women be unveiled. When Reza Shah was forced to abdicate in 1941 by the invading British because of his cordial ties with Germany, the rule was relaxed, and hijab became a matter of personal choice. In Shamshiri’s family, they chose to wear it. She would choose to do so still, although now there is no choice.

In the alcohol-free piano bar of the Espinas Hotel in central Tehran, her hair concealed under flowered silk, Dr. Shamshiri is a handsome woman with striking eyebrows. She was born in Tabriz in northwest Iran, near the border with what was then the Soviet Union. In that region known as Iranian Azerbaijan, a woman felt naked in public with her head uncovered. Her family was devout, but her father was also a high school teacher who gave his blessing to her desire for education. “Although,” she remembers, “he did not want people to know that his daughter was attending university.”

During her fourth year of studies in Tehran, the utterly unexpected happened. Like his father before him, the Shah of Iran had grown more despised over time. His loss of public trust began with a 1953 coup that deposed a popular prime minister who had dared to nationalize Iran’s oil industry, because 80 percent of profits went to the drilling company known today as BP, née British Petroleum. With Shah Pahlavi’s cooperation, the coup was engineered by Britain’s M16 and the CIA (the United States having assumed, erroneously, that the prime minister was a communist).

In the mid-1970s, the Shah, ostensibly a constitutional monarch, abolished every political party except his own, which incited spontaneous strikes. A high-ranking Shi’a cleric named Ruhollah Khomeini, exiled for denouncing the Shah’s lavish rule from the Peacock Throne and his coziness with the West, became a symbol of defiance in absentia. The strikes intensified and organized, until millions filled the streets. Suddenly to everyone’s shock, in January 1979 the Shah fled to Egypt. A year later he died from lymphoma.

The bloodless revolution that toppled him had been joined across the country’s political spectrum, from orthodox mullahs to intellectuals. When the triumphant Ayatollah Khomeini returned from exile in France, even soldiers in the Shah’s army celebrated. A referendum on whether the monarchy should be abolished in favor of Islamic government won 98 percent approval.

The victorious citizenry widely believed that in newly liberated Iran, both secular and religious would live and worship as they liked, with Ayatollah Khomeini as the country’s guiding spirit. Soon, however, Iranians learned that Khomeini’s idea of spiritual leadership was not mere guidance, but theocracy. Although the revolutionary constitution had established a democracy, Khomeini anointed himself Supreme Leader, with a Guardian Council of religious clerics holding veto power over parliament, president, and prime minister. Among his first edicts was reinstatement of the compulsory hijab. Women’s heads must be covered, and their bodies cloaked in chadors or long, loose-fitting garments.

The victorious citizenry widely believed that in newly liberated Iran, both secular and religious would live and worship as they liked, with Ayatollah Khomeini as the country’s guiding spirit. Soon, however, Iranians learned that Khomeini’s idea of spiritual leadership was not mere guidance, but theocracy. Although the revolutionary constitution had established a democracy, Khomeini anointed himself Supreme Leader, with a Guardian Council of religious clerics holding veto power over parliament, president, and prime minister. Among his first edicts was reinstatement of the compulsory hijab. Women’s heads must be covered, and their bodies cloaked in chadors or long, loose-fitting garments.

Secular Iranians felt betrayed. But as Hourieh Shamshiri entered her specialized studies in gynecology, her divided country suddenly united behind the Ayatollah, because Iran was attacked. Shortly after the Ayatollah Khomeini’s ascension, across Iran’s western border Saddam Hussein had assumed the presidency of Iraq. For thirteen years, Khomeini had lived there in exile, stirring revolutionary fervor among Iraqi Shi’ite Muslims until Hussein, a nominal Sunni and Iraq’s military strongman, finally pushed him out of the country. A year later, as Iran was still reorganizing after centuries of dynastic rule, Hussein seized the chance to invade his weakened, distracted neighbor, whose oil-rich Khuzestan province he coveted.

A decade later Saddam would try the same thing in Kuwait, and the United States would respond by invading to protect international petroleum interests. But no such help was forthcoming to Iran. During the chaotic infancy of Iran’s Islamic Republic, a group of students, incensed that the Shah was receiving treatment for his declining health in Texas, stormed the U.S. Embassy. For 444 days, they held fifty-two embassy staffers hostage. Among the upshots of that crisis was American backing for Saddam’s Iraq, in what became the twentieth-century’s longest war between conventional armies.

Iraq struck with ground forces, missiles, and mustard gas. It had the support of both the USSR and NATO, which supplied its armaments, including feedstock for nerve gas. Iran, with more than three times the population, responded with repeated waves of soldiers. Within two years, it suffered tremendous human casualties but regained the ground lost to Saddam’s initial incursions. The two countries then dug in for six more years of entrenched warfare, during which hundreds of thousands of Iranians died.

Before its Islamic Revolution, Iran had begun a family-planning program, following a 1966 census that showed a startling increase over the previous decade. In 1956, Iran had 18.9 million people, but Iranian women were averaging 7.7 children apiece. In only ten years, they added 6 million more. The health ministry began distributing birth control, but with only modest success: the 1976 census still showed fertility rates of 6.3 children per woman. The top-down program was training medical personnel, but failing to explain to parents why they might want to limit the size of their families.

By the time of the 1979 revolution, there were 37 million Iranians. Although many mullahs extolled traditional virtues of early marriage and large families, the Ministry of Health was able to keep its family-planning program. The Supreme Leader himself clarified religious questions about artificial birth control with a fatwa stating that it was permitted. But war with Iraq changed everything. The Population and Family Planning office closed. In its place was a campaign for every fertile Iranian woman to help build Iran a “Twenty Million Man Army.”

The legal marrying age for girls dropped from eighteen to thirteen. To encourage women to bear many children, ration cards were issued on a per capita basis, including newborns. According to Iranian demographer- historian Mohammad Jalal Abbasi-Shavazi, rationing covered not only foodstuffs, but “consumer goods like television sets, refrigerators, carpets and even cars.” Because nursing children used little of their allotment, a black market in extra food and appliances became a key source of family income.

As war with Iraq dragged on, the birth rate surpassed Khomeini’s demographic dreams. Although a million Iranian fighters, including mere boys, were martyred by inhaling poison gas, clearing land mines, or charging in human waves into artillery barrages, the 1986 census counted nearly 50 million Iranians: a doubling in two decades. By some estimates, the growth rate peaked at 4.2 percent, near the biological limits for fertile women and the highest rate of population increase the world had ever seen.

Tehran, an inland city, grew prosperous and populous because of plentiful springs in the Alborz Mountains, which form its snowy backdrop to the north—a vista that, smog permitting, includes 18,000-foot Mt. Damavand, the highest volcano in Asia. From north Tehran’s posh foothills, the city descends two thousand feet through a broad middle-class swathe, dropping into an arid plain filled with working-class neighborhoods that end in south Tehran’s fringe of hovels. Down there, females are invariably enveloped in black fabric, but through much of Tehran, women perform daily fashion miracles, defying the intent of modesty laws by making what is barely hidden all the more alluring. Obligatory long manteaus tighten at the hips and bodices of shoppers in tailored jeans and spiky heels. By sheer numbers, women contriving to conceal the least amount of hair under gauzy hijabs overwhelm morality police trying to enforce shariah dress code. They are further undermined by hundreds of stores selling hair extensions, makeup, wigs, hair clasps, and lingerie — the latter is even sold in the gift shop at the Ayatollah Khomeini’s tomb. Smuggling networks widely assumed to be run by the Ayatollah’s Revolutionary Guards help keep stores stocked with European and New York haute couture—sluiced, like the BMWs and Lamborghinis of north Tehran, through portals like Dubai.

Even during sanctions, Tehran, like Havana, thrums with energy. But it lives on time borrowed from mountain springs recharged by rain. In 1900, they easily supported the 150,000 Tehranis. Counting the 3 million workers who commute here daily, 15 million drain that water today, a hundred-fold increase in just over a century. Khomeini’s divine mandate to build not just an army, but an Islamic generation with no memory of the Shah, spawned as breathtaking a demographic leap as the world had ever seen — which made what came next all the more astonishing.

Even during sanctions, Tehran, like Havana, thrums with energy. But it lives on time borrowed from mountain springs recharged by rain. In 1900, they easily supported the 150,000 Tehranis. Counting the 3 million workers who commute here daily, 15 million drain that water today, a hundred-fold increase in just over a century. Khomeini’s divine mandate to build not just an army, but an Islamic generation with no memory of the Shah, spawned as breathtaking a demographic leap as the world had ever seen — which made what came next all the more astonishing.

IN 1987, DR. HOURIEH SHAMSHIRI MILANI finished her obstetrics and gynecology residency in Tehran. During the war, her specialty had become politicized, as demographics became the most potent weapon in Iran’s arsenal. With the stunning 1986 census figures, Iran’s prime minister declared their new huge population “God-sent.” But others—especially the director of Iran’s planning and budget office — were plain frightened. As the stalemated war headed to a UN-brokered ceasefire, his office calculated the numbers that their shattered economy might reasonably support. All those males born to man the Twenty Million Man Army would need jobs, and chances for providing them shrank with each new birth.

Secret meetings commenced with the Supreme Leader to discuss the population blessing that was now a population crisis. Years later, demographer and population historian Abbasi-Shavazi would interview the 1987 planning and budget director, and learn that he had met with the president’s cabinet and explained what excessive human numbers portended for the nation’s future. To feed, educate, house, and employ everyone would far outstrip their capacity, as Iran was exhausted and nearly bankrupt. There were so many children that primary schools had to move from double to triple shifts. The planning and budget director and the minister of health presented an initiative to reverse demographic course and institute a nationwide family-planning campaign. It was approved by a single vote.

A month after the August 1988 ceasefire finally ended the war, Iran’s religious leaders, demographers, budget experts, and health minister gathered for a summit conference on population in the eastern city of Mashhad, one of holiest cities for the world’s Shi’ite Muslims, whose name means “place of martyrdom.” The weighty symbolism was clear.

“The report of the demographers and budget officers was given to Khomeini,” Dr. Shamshiri recalls. The economic prognosis for their overpopulated nation must have been very dire, given the Ayatollah’s contempt for economists, whom he often referred to as donkeys.

“After he heard it, he said, ‘Do what is necessary.’ ”

It meant convincing 50 million Iranians of the opposite of what they’d heard for the past eight years: that their patriotic duty was to be forcibly fruitful. Now, a new slogan was strung from banners, repeated on billboards, plastered on walls, broadcast on television, and preached at Friday prayers by the same mullahs who once enjoined them to produce a great Islamic generation by making more babies:

One is good. Two is enough.

The next year, 1989, Imam Khomeini died. The same prime minister who had hailed fertility rates approaching nine children per woman as God-sent now launched a new national family-planning program. Unlike China, the decision of how many was left to the parents. No law forbade them from having ten if they chose. But no one did. Instead, what happened next was the most stunning reversal of population growth in human history. Twelve years later, the Iranian minister of health would accept the United Nations Population Award for the most enlightened and successful approach to family planning the world had ever seen.

If it all was voluntary, how did Iran do it?

Nodding to the Persian music issuing from the piano, Dr. Shamshiri smiles, remembering. “We used horses. Doctors and surgeons, teams from universities, carrying our equipment on horseback to every little village.”

The horseback brigades that Dr. Hourieh Shamshiri and her fellow OB-GYNs accompanied to the farthest reaches of the country made any kind of birth control — from condoms and pills to surgery — available to every Iranian, for free. Because Ayatollah Khomeini’s original contraception fatwa emphasized that neither mother nor child should be harmed, it was assumed to exclude both abortion and operations. But his successor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, issued a fatwa of his own —“When wisdom dictates that you do not need more children, a vasectomy is permissible”—that was interpreted to include tubal ligations for women.

The program’s initial goals were modest. According to Mohammad Abbasi-Shavazi, they hoped to reduce the average fertility rate of Iranian women to four children by 2011, and eventually drop the population growth rate from its astronomical levels during the war to slightly above replacement rate. But Iranian families were just as broke and fatigued as the nation, and they leaped at the chance for fewer children. Within two years, Iran’s demographers were disbelieving their own numbers.

The horseback doctors had planned to encourage women — who were not required to seek husbands’ approval for birth control — to space pregnancies three to four years. They were to advise them to bear children only between ages eighteen and thirty-five, and to suggest stopping with three children. “But every woman who already had children wanted an operation,” says Dr. Shamshiri. “More than a hundred thousand women of that generation were sterilized. All the younger ones told me they only wanted two, one of each if they could. I’d ask them why. ‘The cost of rearing children,’ was the first thing they said. So I’d ask them to imagine that tomorrow their economic problems had been solved, how many children would they want. Again, they answered, ‘Two, because of education. We should send our daughters to university.’ ”

They were seeing modern women on television — including herself, as she and other gynecologists were now frequently on Iranian TV programs. “Families would find my telephone number. They’d ask, ‘How did you get this degree? How can we educate our daughters like you?’ ”

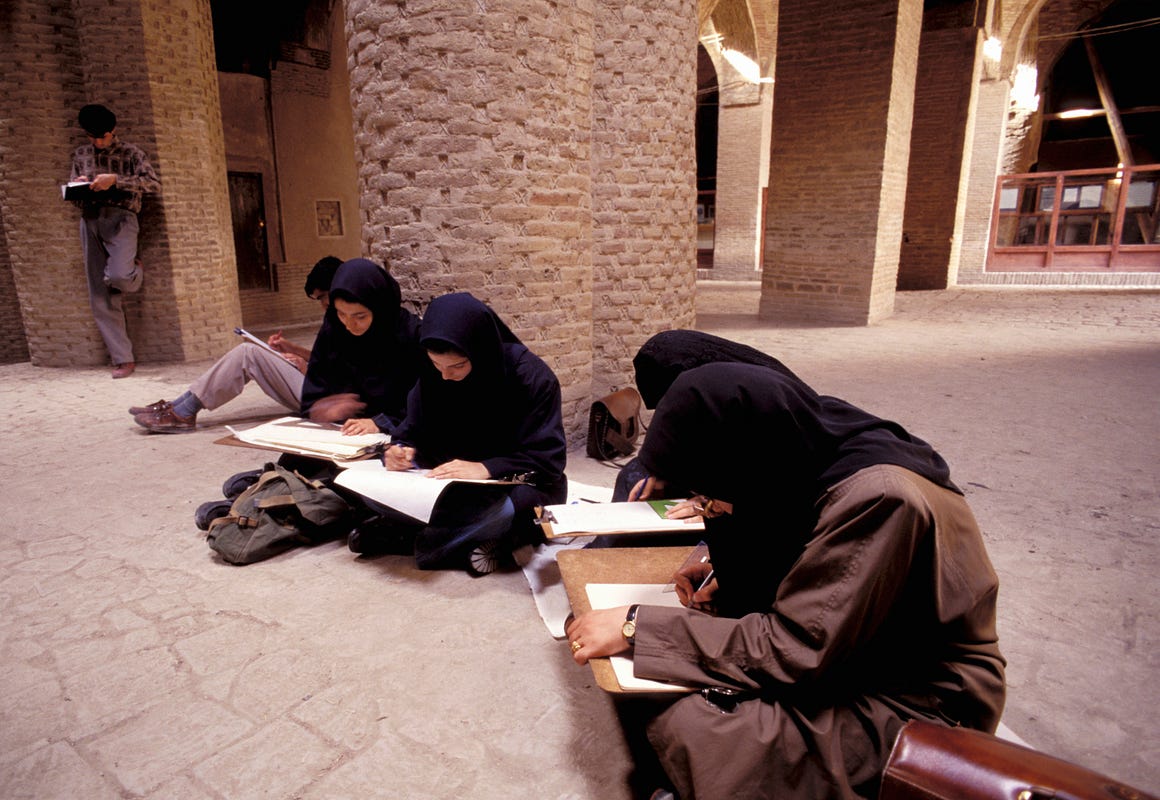

Increasingly, the answer was easy. All the accolades that Iran’s family- planning program received in forthcoming years cited one indispensable factor: female education. Not just primary and secondary, but university. In 1975, barely a third of Iranian women could read. In 2012, more than 60 percent of Iranian university students were female. The literacy rate for females twenty-six and under was 96 percent. Giving women control over their wombs and their education made it increasingly hard to deny them the workplace. By 2012, one-third of government employees in Iran were women. As Dr. Shamshiri recalls her horseback missions, two taxis arrive at the Espinas Hotel driven by female cabbies, while just beyond, women police officers cruise Keshavarz Avenue.

At one point during the push to a Twenty Million Man Army, the marriage age for girls dropped again, to nine—the “official age of puberty.” With the family-planning program, that was repealed, and the average age of a bride soon rose to twenty-two, as women postponed marriage and childbearing until they finished school. By the 1994 World Population Conference in Cairo, the numbers from Iran were so astounding that UNFPA sent its demographers to check the figures that Abbasi-Shavazi and his colleagues were collecting — and got the same results. Dr. Hourieh Shamshiri, by then a deputy in Iran’s Ministry of Health, was a delegate, and was besieged with questions. Everyone wanted to know how such a thing could happen in a Muslim nation—and with a voluntary program, no less.

There was no covert coercion, she’d explain. The sole requirement was that all couples attend premarital classes, held in mosques or in health centers where couples went for prenuptial blood tests. The classes taught contraception and sex education, and stressed the advantages of having fewer children to feed, clothe, and school. The only governmental disincentive was elimination of the individual subsidy for food, electricity, telephone, and appliances for any child after the first three.

By 2000, Iran’s total fertility rate reached replacement level, 2.1 children per woman, a year faster than China’s compulsory one-child policy. In 2012, it was 1.7.

“Iran’s family-planning program succeeded,” says Mohammad Jalal Abbasi-Shavazi, “thanks to the Islamic revolution. There was a national commitment to reduce the gaps from the Shah’s time between rich and poor, urban and rural.”

Under the Shah, agriculture ministers rarely left Tehran. Now water, sanitation, agriculture, energy, and finance officers arrived in the remotest villages, extending technical help during planting, installing toilets, launching literacy programs. “Most important was building a health network that reached the farthest outposts of the country.”

Every hamlet in Iran today has a “health house,” staffed by two behvarz selected by the village. Usually a man and a woman, they receive two years of training in family medicine, including prenatal and postnatal care, contraception, and immunization. For illness, there is a rural clinic for every five health houses, staffed by doctors, who also visit each health house twice a week.

The behvarz maintain birth, death, and vaccination records for each person. In Iranian cities, teams of women volunteers go door-to-door, doing the same. With such oversight, the spread of diseases like tuberculosis was checked, and Iran’s infant mortality rate dropped to western European levels, further convincing parents to limit family size.

It was to these health houses that Hourieh Shamshiri, her fellow OB-GYNs, and horseback mobile surgical teams would arrive. As Iran’s postwar economy improved, horses gave way to four-wheel-drive vehicles and even helicopters. Iran pioneered “no-scalpel” vasectomies, ten-minute procedures involving just a tiny puncture in the abdomen. During the early years of the revolution, contraceptives were often hard to find. Now Iran became one of the world’s biggest producers of condoms. Several months’ worth of contraceptive supplies were stockpiled to assure that shortages didn’t occur. And everything—condoms, pills, IUDs, injections, vasectomies, and tubal ligations — remained free.

Nevertheless, demographers report, the preferred method of contraception in Iranian cities remains coitus interruptus. One reason may be that the cautionary tale in Genesis of Onan, whom God kills for disobeying his father by spilling his seed on the ground, has no equivalent in Islam: according to Hadith commentaries to the Qur’an, the Prophet Muhammad did not forbid withdrawal, known as al-azl.

According to Dr. Shamshiri, the truth is more mundane. “It’s the usual fear of side effects, and dislike of using condoms. Which is why sterilization and vasectomies are so popular, once people have the children they desire.”

One other country where reliance on withdrawal is similarly high is Italy, which also has low fertility rates and, coincidentally, is also home to a theocracy — albeit a theocracy reduced to 110 acres in which no females reside. Outside the Vatican walls, abortion is legal during the first trimester. In Iran, however, abortion is prohibited, despite suggestions in the Qur’an that the soul does not enter a fetus until the fourth month of pregnancy.

“Abortion is still illegal,” says Dr. Shamshiri, now a professor at Tehran’s Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science. “A few years ago, Parliament expanded a rule about saving a mother’s life to include therapeutic abortion. It took hard work to pass this.”

In the halls of Parliament, religious authorities had confronted her. “Abortion is killing. Why do you write papers supporting it?” the mullahs demanded.

“You asked today if a fetus is a person or not,” she replied. “Because, you said, if a fetus is a person, you can’t kill it.”

They nodded.

“It’s worth discussing. But first, I hope you agree that a woman is a person.”

On religious grounds, it is difficult for her. “As a matter of women’s rights, I support abortion. But personally, I don’t agree. I won’t do abortions myself. If I have a patient with breast cancer who needs a therapeutic abortion, I refer her. But women should use family planning if they don’t want pregnancy. If they do, the need for abortion becomes very rare.”

Rare, but never zero. Condoms can break. Antibiotics can lower the effectiveness of pills. And al-azl has a notable failure rate. In Iran, as everywhere, women find ways to have an abortion. In wealthy North Tehran, where women see private doctors, it is not hard to find physicians to perform safe abortions. Dr. Shamshiri’s concern is for poor women whose contraceptives fail. “We have a street in Tehran where illegal drugs are sold, including abortive drugs. People go there and buy suppositories. That is not safe. That’s why it is important to provide women this service.”

In 2005, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a conservative ex-mayor of Tehran popular among the working class, was elected president of Iran. In 2006, he proclaimed that Iran’s family-planning program was un-Islamic. He called for women sixteen or older to leave the universities, get married, and get pregnant. Iran’s 70 million population, he said, needed to add 50 million more. His pronouncement helped spur Iranian women to collect a million signatures demanding repeal of all laws that denied them equality, a campaign that won many international women’s rights awards.

In June 2009, in what was overwhelmingly believed a rigged result, Ahmadinejad was reelected over a moderate reform candidate. The streets of Iranian cities filled with hundreds of thousands protesters, the majority female. When a philosophy student named Neda Agha-Soltan was shot by a member of the Ayatollah’s paramilitary volunteer militia, her death, captured on video, was seen by millions around the world.

Iran’s so-called Green Revolution, named for the moderate opposition leader’s campaign color, became an inspiration for the Arab Spring uprisings. But the regime’s brutish response—at least seventy slain, and hundreds more imprisoned — sapped its energy. The massive street gatherings are gone, but as one anonymous participant says, “This revealed how corrupt the Revolution has become. The love we feel for Islam has been undermined by our contempt for the mullahs who mix mosque and state, and are destroying both in the process.”

The newly reelected President Ahmadinejad reiterated his call to nearly double the population, which was denounced in Parliament, in the Ministry of Health, and even by some clerics. His offer of 10 million rials—about US$1,000—for every new baby backfired when the math of population increase was explained to him and he realized that his goal, 1.35 million new children per year, would cost more than a billion dollars annually. His modification — the money would be held in trust, and given to the child at age eighteen—earned even more derision, and women ignored it.

“The preference for one or two children, or even none, is now woven into the cultural fabric of the nation,” said demographer Abbasi-Shavazi in 2011. “What will happen is what women want. And they don’t want three.”

“I once read,” says Hourieh Shamshiri, “that you save women so that women will save the world. My Muslim religion is a pure one in which woman is as human as man, and their rights are equal. We have a sentence in the Holy Qur’an that means ‘We created you from the same soul.’ Different shapes, but the same soul.”

ii. Carpets

FOR CENTURIES, THE CULTURAL FABRIC of Iran has been woven by Persian carpet makers. In Turkish rugs, each strand of yarn is knotted around two warp strands, but Persian rugs, with one weft per each warp, are twice as tight. The tightest still made today, in Iranian cities such as Esfahan, have 144 knots per square centimeter. A rug like that, of wool from the bellies of spring lambs, can take two people eight years to finish. In Tehran’s Carpet Museum hang old masterpieces created for royal families with 160 knots per centimeter, woven by girls with sharp eyes and tiny fingers. One fabulously complex floral pattern that measures 320 square feet took three people working ten hours day eighteen years to complete—the principal weaver was seventeen when she started, and thirty-five when it was finished.

As a biology student in the 1960s, Esmail Kahrom would stare at rugs in the museum, such as one completed in 1416 that depicts the Tree of Life, a Zoroastrian symbol that predates Islam. Among its branches he recognized turkeys, bustards, vultures, mynahs, owls, doves, thrushes, hoopoes, flamingoes, swallows, quail, parrots, ostriches, and partridges. Around the trunk crawled bears, turtles, alligators, beetles, centipedes, lions, and leopards.

The depictions were so detailed that zoologists could determine each species. He was looking, Kahrom understood, at creatures now extinct in his land. The eyes of ancient carpet weavers are how Iranian biologists today know what once lived here.

Esmail Kahrom was the son of an air force pilot who, like his mother, was one of twelve children. As a boy, his father would take him riding in Khosh Yelagh, a wildlife refuge whose name means good summer pasture, in the eastern Alborz Mountains watershed, just south of the Caspian Sea. The grass there grew so tall that he would lose sight of the park ranger guide and have to stand on his horse’s back to see where the stalks were moving, to know which way to go. Khosh Yelagh was then home to the largest population of cheetahs in Iran. The sight of the fleet creatures thrilled him, and he resolved to become a naturalist.

After graduating from the University of Shiraz, he became a field ornithologist with the Department of the Environment, and traveled to every ecosystem in Iran. Eventually he was appointed director of the Bureau of Wildlife, and began a weekly television program that introduced viewers to the natural wonders of their country. The government sent him to England for graduate studies. After receiving his doctorate at the University of Wales, he returned to Iran to teach ecology, both in college and through the media.

His TV documentaries made Esmail Kahrom Iran’s best-known naturalist. He took viewers to places like Miankaleh, a forty-eight-kilometer sandy peninsula that is the last stretch of natural shoreline along Iran’s eight-hundred-kilometer Caspian seacoast, where half of Iran’s 504 bird species are found. In the early seventeenth century, Shah Abbas of Persia’s Safavid dynasty once killed 90 leopards and 30 tigers there. In 1830, Naser al-Din Shah of the Qajar dynasty, who had eighty-five wives, wrote that early one spring morning he watched millions of migrating birds darken the skies for four hours. Fifty years later, one of his many sons would take a group of friends to Miankaleh. With newly invented high-powered rifles, they shot 6,000 pheasants, 150 deer, 63 buffaloes, 18 leopards, and 35 tigers.

That same prince later described an area outside the southern city of Shiraz where hundreds of men hunted day and night. “The mountain is so rich in wildlife,” he wrote in his memoirs, “that if the numbers of hunters were ten times over, there would still be enough game animals for everybody. We stayed here for two months and when we were leaving, the number of animals was still the same.”

“Statements like these,” Kahrom told his audiences, “prove that the Qajar hunters never set out to eradicate entire species of wild animals. In fact, they hoped to hunt forever. They considered natural resources such as wildlife and forests to be renewable resources that simply could not be exterminated by man. But all the species they prized are now rare, or threatened, or extinct: the mighty lion, the Caspian tiger, the Iranian wild ass, gazelles, big-horned mountain sheep, leopards, and the cheetah.”

“Yes, the cheetah,” he says, passing a plate of figs. The walls of his home near Tehran’s Islamic Azad University, where he teaches, are trimmed with ornate molding and hung with brass wall sconces and chandeliers. Small Persian rugs cover the hardwood floors. The brick fireplace is flanked by paintings of migrating cranes and the endangered red- breasted goose that winters in Miankaleh. Above the mantle, a nineteenth-century Tabriz tapestry declares in graceful Farsi calligraphy that God is the greatest protector of all.

Whenever Kahrom, a dapper man with a sandy moustache who favors ascots, is confronted by someone demanding to know whether it really matters if cheetahs disappear from the face of the Earth, or if tigers go extinct, he tells them about one particular cheetah.

It was where he’d least expected to encounter one. It was January 2003, and he was visiting America for the first time. A cousin in San Diego had married a schoolteacher, who invited him to observe a sixth-grade class. He was charmed that the teacher had brought an Iranian flag and Iranian coins to show the students. When she next unrolled an exquisite crimson rug, his eyes widened. The rug, he knew immediately, was a pure silk paisley pattern from the holy city of Qom, worth thousands.

“Our guest is an ecologist,” she told her students. Ecology, she explained, is the science of how everything on Earth—people, plants, animals, fungi, microbes, rocks, soil, water, and air—is connected. “All over the world, there are people who protect animals and plants so that the connections don’t break. Dr. Kahrom is one of them.”

There was a knock on the classroom door, and Kahrom gasped along with the sixth-graders as another teacher entered, accompanied by a curator from the San Diego Zoo. The leash he held was attached to a muzzled cheetah.

“There are two populations of cheetahs,” said the teacher, “one in Africa, the other in Asia. The Asiatic cheetah today lives only in Iran.” Kahrom was amazed that this American woman knew something he wished his own people comprehended.

“What do you think would happen,” she asked, “if Asiatic cheetahs disappear from the Earth? Would it be a disaster? Would we be in trouble? Would you still be able to go to school? Will there still be gasoline for your father’s car? Will we have electricity and water? Should we be concerned?”

The students agreed that this elegant creature, silent on its haunches before them, deserved to live. But none thought that their world would come crashing down along with the cheetah’s, in the event it didn’t.

The teacher turned to the glowing silk Qom rug, draped on an easel. “This beautiful Persian carpet belongs to an Iranian who lives in San Diego. It’s made with more than one-and-a-half million knots. It took women years to do that. Now, suppose some boy with a pair of scissors cuts a few knots from its edge. What will happen? Nothing. You will not even notice it.

“Now, suppose that he returns and makes two hundred knots disappear. Probably you still wouldn’t notice it among the one-and-a-half million. But what if he keeps doing it? Soon you’ll have a small hole. Then it will get bigger, and bigger. Eventually, nothing will be left of this carpet.”

Extending her arms, she pointed at the La Jolla foliage outside and at the cheetah that was watching her as raptly as her students and Kahrom. “All this is the carpet of life. You are sitting on it. Each of those knots represents one plant or animal. They, and the air we breathe, the water we drink, and our groceries are not manufactured. They are produced by what we call nature. This rug represents that nature. If something happens in Asia or Africa and a cheetah disappears, that is one knot from the carpet. If you understand that, you’ll realize that we are living on a very limited number of species and resources, on which our life depends.”

In the Miankaleh Wildlife Refuge, park director Ali Abutalibi has watched the knots unravel all his life. His father, a shepherd in the nearby hills, had to guard his flocks from leopards and wolves. Now maybe ten wolves remain. The last leopard here was killed by a hunter in 2001; four years later, the last tiger; a year after that, the last elk. Without the top predators, the jackals and wild boars exploded. Feral horses and cows roam the preserve, decimating the grasses and berries.

During Abutalibi’s boyhood, migrating wetland birds overhead still numbered in thousands. “Swans, geese, pelicans, flamingoes, spoonbills, ducks. Also pheasants, bustards, francolins. We would hunt on horseback. You could kill two hundred birds in ten minutes.” Embarrassed, his fingers work his white prayer beads. “That was before I became an environmentalist.”

The park, whose willows, alders, and wild pomegranates were once part of a forest that spanned the entire coastline, is now abutted by soy, cotton, rice, and watermelon fields heavily dosed with agrochemicals. An adjacent wetland to the west disappeared under a port facility, where lights that blaze all night chased off thirty thousand nesting shorebirds. An invasion of jellyfish via a shipping canal that connects the Black Sea to the Volga River, which then flows to the Caspian, has devoured 75 percent of the zooplankton. Caught between algae blooms, the fouling from offshore drilling rigs, and poaching, the 200-million-year-old Caspian sturgeon, source of the world’s black caviar, is nearly extinct.

“So many fish are gone,” says Abutalibi, looking over the pale green sea. And the creatures that eat them: he now sees a Caspian seal only every few months. He lets local shepherds fish for shad and white trout, limiting them to two apiece, but the poachers who sneak in know no limits.

“There used to be forty hunters here — now there are three hundred,” he says, running fingers through thinning curls. “God told the Prophet Nuh2 to save all the animals because the life of man depends on them. Without them, what will we do? If we kill everything except for cows and chickens, can we live in a world without birds that sing?”

West of the Miankaleh refuge is the city of Ramsar, where in 1971, eighteen nations signed one of the most important global environmental treaties: the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance. Today, there are 164 signatories. Ramsar’s own wetlands, however, have all but vanished beneath roads, tea plantations, hotels, and the villas of wealthy Tehranis.

To the east of Miankaleh lies Golestan National Park, Iran’s oldest and biggest. Its name means rose garden, for its fragrant native flower. In Golestan, mountains are still thick with cypress, cedar, and Persian juniper. This is the largest remnant of Iran’s great Hirkani Forest, a relic that escaped freezing during the Ice Ages. Below the conifers are stands of oak, maple, wild cherry, and barberry, and valleys filled with wild saffron. Beyond them are the steppes where, in wetter times, Esmail Kahrom rode through grasslands taller than his mount. Most of the riding here now is done by car: Despite the pleading of every ecologist in Iran, an east-west expressway completed over the last decade now bisects the park.

“This road is our biggest sorrow,” says head Golestan environmentalist Jabad Selvari. His clean-shaven cheeks burn when he thinks how easily the highway could have been routed a few miles south. They didn’t even build underpasses for the animals. Now, oil tankers from Iraq and buses from Turkey bore through, their diesel roar filling Golestan’s canyons and waterfalls. The highway divides breeding populations of gazelles, endangered ibex, elk, roe deer, curly-horned urial sheep, three species of wildcat, and leopards. And it makes it nearly impossible to stop poaching, especially the trapping of sparrow hawks and red kites for the falconry market.

“Rich Arabs and Turks pay up to $60,000 US for these birds,” says park superintendant Mohammad Rezah Mullah Abbasi. Smugglers, he says, can hide three falcons, their talons and wings bound, inside hollow truck doors. “We are fanatics like Taliban to preserve nature,” he jokes, “if we inspect and find blood or feathers.”

But it’s no joke to them. The shoulder patches on their khaki uniforms show a leopard and the words Environmental Guard in Farsi and English. The leopard is the symbol of their park; every year, they find the skinned bodies.

“In the seventies, when Iran had half our current population,” Selvari says, watching a golden eagle swoop over the rippling saffron, “there were still tigers and lions here.”

iii. The Missing River

IN IRAN TODAY, HIGHWAYS ARE built mainly by companies owned by the Ayatollah’s Revolutionary Guards. After the Iraq war ended, this elite branch of Iran’s military began forming corporations to create jobs for itself. Over three decades, it became Iran’s biggest conglomerate, with interests in both legitimate business and black-market smuggling, including alcohol, drugs, and allegedly even prostitutes, channeling Iranian girls to Dubai. As the protector of the ruling ayatollahs, it gets first choice of public works contracts.

Most lucrative are dams: Iran is the third biggest dam builder in the world, with six hundred completed and hundreds more under way. “Think of the Revolutionary Guards,” says an Iranian scientist who studied in the United States, “as a combination of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Mafia.” Many Iranian dams are built mainly for the huge construction contracts, he says, with little regard for how much water they can actually impound or the damage they wreak. Northwest Iran’s Lake Urmia, the world’s third largest saltwater lake and both a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and a Ramsar wetland site, is now half its former size and may disappear altogether, because thirty-five dams have been built on rivers that feed it. When the Ministry of Energy consulted with Esmail Kahrom about the Urmia situation, he warned them that the homes of 14 million people were in danger of being lost to blowing salt, not to mention the habitat of 210 waterfowl species.

Kahrom advised them to stop building ten dams already under way, and release 20 percent of the water behind the others to resuscitate Lake Urmia until rains replenish it and the reservoirs.

“We don’t have any water behind the dams,” he was told.

“If you don’t have any water, then why did you build thirty-five dams? And why you are planning a total of seventy-seven?”

Nevertheless, in 2011 Iran’s parliament rejected a motion to increase inflows to Lake Urmia, the biggest lake in the Middle East, to save it from extinction. Should it dry completely, scientists fear that it could release 8 billion tons of windblown salt storms over cities in Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Azerbaijan.

In the central Iranian city of Esfahan, three environmental scientists gather in a house on Abbas Abad Street to discuss a tragedy even more imminent and possibly greater than Urmia. Abbas Abad, lined with plane trees that form a magnificent arch, is often called the most beautiful street in one of the world’s most beautiful cities. The seat of Persian government during the sixteenth-century Safavid dynasty, Esfahan is a marvel of Islamic architecture. The overpowering Shah Mosque in Naghsh-e Jahan Square, the world’s second biggest after Beijing’s Tiananmen, is an astonishment in blue mosaic. But even more than its domes and minarets, the loveliness of Esfahan derives from five covered stone bridges over the Zayanderud, a river that flows across the city.

Along the Zayanderud’s banks, girls in black headscarves glide on rollerblades over paths that wind through a green belt of plane trees, weeping willows, and topiary shrubbery. The paths lead to the bridges, such as double-decked Khaju, with its cool arcade where picnickers take tea on broad stone benches and watch the sunset framed through the bridge’s arches. Built in 1560, the arches were engineered acoustically so that when Sufi poetry is recited or music played on summer evenings, it can be heard along the bridge’s entire length.

A mile farther downstream, it is believed impossible for a couple strolling by night on the Si-o-se Po Bridge, its thirty-three arches reflected on the Zayanderud’s water, not to fall in love. Except since 2008, there has been no water. The riverbed is now dry sand, where men cross on bicycles and boys play soccer.

“For a few weeks during winter they open the sluice gates on the dams to keep the foundations of the bridges wet, or they’ll crumble.”

Mehdi Basiri, a retired professor of environmental science at the Esfahan University of Technology, is meeting with Ahmad Khatoonabadi, who teaches sustainable development, and plant geneticist Aghafakhr Mirlohi. The three have formed Green Message, an environmental NGO whose mission is to get through to decision makers. They haven’t had much luck.

“In any ecosystem,” says Basiri, “the limiting factor is water. But the government never thinks about it. In 1966, Esfahan had two hundred thousand people. Today, 3.5 million. There is huge pressure on the aquifers and river. But what do they do? They build steel mills, aircraft plants, stonecutting and brick-making plants, all demanding water.”

“They plant rice, a crop that doesn’t belong here, which evaporates more water,” says Khatoonabadi.

Worst, they built pipelines north and east, to carry Za ̄yanderu ̄d water to the desert cities of Qom and Yazd. “It’s just like Lake Urmia,” says Basiri. “They build forty dams, dry it up, then ask the government for money to build a two-hundred-kilometer pipeline from somewhere else to bring in water to refill it.” On the outskirts of Qom and Yadz, well-connected landowners are irrigating new pistachio groves. “And now they’re building steel mills and tile factories there, too.”

“They convert rangeland to orchards, leaving no water for native plants,” says Mirlohi. “The water table drops, the land settles. The Si-o-se Po Bridge is damaged. The historical buildings are in danger.”

But it’s not just about buildings and bridges, he says. “I think we have only a few years to survive.”

Basiri’s living room grows quiet as the men sip chai. They have a petition with the signatures of thousands of people brave enough to demand that water be returned to the river that defines their city. “But a third of the national budget is now used for building dams. When so much money is involved, you can’t stop it.”

A mile away, in an echoey, fluorescent-lit community house basement, four women are trying, regardless. The leader of the group is a middle-aged, self-described nature lover; one is a dentist; another is a hydrologist; the other a recent graduate in ecology. They are with the Esfahan chapter of one of Iran’s fiercest NGOs, the Women’s Society Against Environmental Pollution. It was founded by Mahlagha Mallah, a University of Tehran librarian who, in 1973, was puzzled by a book on an unfamiliar topic: environmental pollution. Not knowing where to catalog it, she ended up reading it cover to cover. A granddaughter of Iran’s first feminist writer, Bibi Khanoom Astarabadi, Mallah became a pioneer in the Iranian environmental movement. Revolution and war with Iraq interrupted her efforts, but during the 1990s, at age seventy-four, she began traveling around Iran to organize chapters of her new NGO.

“Women,” she told recruits, “are instinctive teachers. We’re also the world’s main consumers: most advertisements try to attract us. We produce the most household waste. But just as population control rests with us, we can cure our shopping disease and our polluting, and educate our children to care for the environment.”

Still vigorous at ninety-four, she is heroic inspiration to these women who meet monthly to plot how to save their country from itself. They sit in a circle of white plastic chairs, wearing sandals, light manteaux, and colored hijabs, joined by two men in polo shirts: an architect and the dentist’s student son. Usually, about forty appear for meetings; tonight is a special session, because on top of their other travails, there is something new to discuss.

Still vigorous at ninety-four, she is heroic inspiration to these women who meet monthly to plot how to save their country from itself. They sit in a circle of white plastic chairs, wearing sandals, light manteaux, and colored hijabs, joined by two men in polo shirts: an architect and the dentist’s student son. Usually, about forty appear for meetings; tonight is a special session, because on top of their other travails, there is something new to discuss.

Before the Ahmadinejad years, Iran finally seemed to be relaxing its grip on its own people. A reformist president, Mohammad Khatami, was even broaching rapprochement with the West. New voices flourished, and dozens of environmental groups formed. In a 2001 eco-convention attended by hundreds, the Esfahan women heard geologists explain that their river was heading for disaster. They began holding demonstrations and Earth Day events in schools to warn people about the threat to the Za ̄yanderu ̄d.

Then, in 2008, the river actually dried up. Dazed, they stood on the lovely bridges at night and saw no reflection, only darkness. This, they figured, would finally mobilize people. Except, like the scientists’ group, Green Message, they found their NGO accused of being Western spies. News columnists called them hoodlums for wanting to steal water from thirsty people in Qom and Yadz.

“We have an address where people can electronically sign the petition to save the Za ̄yanderu ̄d, but now they block any e-mail that has the word petition in it,” says the nature lover.

“School principals now say we need authorization from the Ministry of Education in Tehran to talk to children about the environment,” says the dentist.

“When we hand out our magazine, Cry of the Earth, we get hassled by men demanding to know who we are,” says the hydrologist. She stands and paces.

“We get hauled into police headquarters and grilled about our environmental pamphlets. We say: ‘We’re glad you asked. They’re about recycling, tree-planting, water conservation, and solar energy. Very dangerous.’ We tell them that their city, the most beautiful in Iran and one of most beautiful in the world, is now one of the most polluted. And that their river is dying and the climate is changing and WHAT DO THEY INTEND TO DO ABOUT IT?” She sits down, reddening.

“Even in Pakistan NGOs can freely contact people,” says the dentist.

They fear that their country has become unhinged. “A new subway is tunneling under Esfahan’s most gorgeous historical buildings. We keep telling them the vibrations will crack, or even collapse the monuments,” says the architect. “But their ears do not hear.”

The one thing that Iran’s authorities have done right, all here agree, is to create the health care and family-planning system. Of course population must be controlled — the land is bursting. Except for the group leader, who is the oldest present and mother of three, the others have two or fewer. “But we’re not allowed to do anything else useful without their permission.”

And now, even permission to control their bodies and decide reproductive matters for themselves is suddenly in doubt.

Just recently, rumor has it, the Ayatollah Khamenei said that people shouldn’t worry about a population crisis until Iran has 120 million people, or 150 million. Maybe then, he added, it will be time to think about the consequences.

“What?” exclaims the dentist. “He’s the one who issued a fatwa about tubal ligations and vasectomies! During my rural service, one day I saw fifteen women get their tubes tied. This is the mentality that Ahmadinejad has put in his head. Can’t anyone see what the pressure of all these people is doing?”

“This is the countdown for the Iranian environment,” says the group’s leader, her fingers twisting the ends of her pale green hijab. “Once again, women will have to pay.”

When the Esfahan women met that night in 2011, Ramadan had just ended. Life in Iran resumed, only with more difficulty: the West, pressured by Israeli and impending American electoral politics, applied ever harsher economic sanctions to try to dissuade the Islamic Republic from developing a nuclear program. Outside the country, it was believed that Iran was building atomic bombs; although the International Atomic Energy Association had found no evidence of attempts to develop nuclear weaponry since 2003, Iran resisted giving inspectors full access to military facilities for verification. Within the country, however, where dying rivers were dammed to squeeze every kilowatt from diminished rainfall, the nuclear program seemed to be about what Iran insisted it was: making energy.

Although Iran had designed the world’s most enlightened and effective family-planning program, it still had decades to wait until the immense baby boom generation of the Iraq war years began to die off and numbers returned to sustainable levels. In the meantime, its 75 million people and its industries demanded electricity, and Israeli rhetoric was goading Iranian hawks to call for nuclear arms as well as power plants. A breathless world wondered if these two enemies would spark a firestorm worse than even the heat of the unmoored climate.

Another Ramadan came, and the Supreme Leader made the rumor official. The family-planning policy, declared Ayatollah Khamenei, “made sense twenty years ago. But its continuation in later years was wrong.”

“Population control programs belonged to the past,” the health minister told the press. Effective immediately, funding for family planning was removed from the national budget, and applied to encouraging larger families. The Ayatollah’s new goal for Iran was 150 to 200 million people. A bill was introduced in Parliament to return the legal marriage age for girls to nine.

Speculation over what changed his mind included fear of another war requiring a mighty army, this time with Israel or even America. Some guessed it was a signal to the West that Iran wasn’t bothered by its sanctions, but rather was abundantly prepared — for abundance. But the Ayatollah himself gave a more prosaic and parsimonious explanation: Demographers, he said, calculated that if the birth rate stayed the same, by 2032 Iran would face a declining, aging population. That would mean more medical and social security costs for seniors, and fewer productive younger people to pay for them. After twenty-plus years of birth control, it was time for a new policy for the next twenty.

President Ahmadinejad’s earlier calls for women to be more fruitful had been fruitless, and many doubted that the new policy would have any abrupt effect. With unemployment and inflation soaring under the West’s sanctions, income was down and couples were even postponing marriage, let alone children. Besides, even if birth control were outlawed, the Revolutionary Guards’ smuggling apparatus would doubtless leap into the breach. The Guards and the Ayatollahs were locked into a symbiosis that neither could easily break: the clerics’ increasingly unpopular regime depended on the Guards’ protection, and purchased their loyalty by turning a blind eye to their limitless enrichment.

What would not continue, however, would be premarital classes, or teams of surgeons flying into the hinterlands to perform free contraceptive surgery for millions of Iranians who otherwise couldn’t afford it. No more free IUDs, pills, or injections.

After years of being able to decide how many children to have, the vast majority of Iranian couples had determined they wanted no more than two. But that was no longer convenient for Iran’s military-industrial theocracy.

And if Iranian women wouldn’t choose to have more children, the regime, by withholding the means, would henceforth be making that decision for them.

//.

This is an excerpt from Countdown: Our last, best hope for a future on earth? by Alan Weisman. Copyright © 2013 by Alan Weisman. Reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Company, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

To learn more about Countdown and the author, visit the website. If you’d like to purchase the entire book, it’s available on Amazon and at Barnes & Noble.

FURTHER READING

No comments:

Post a Comment