Stealth and CIA drones omitted from 30-year outline

David Axe in War is Boring

The U.S. Defense Department has published an updated version of its three-decade unmanned vehicle “roadmap,” which describes what kinds of robots the Pentagon has now and wants to acquire in the future, and how much money it expects to spend doing so—no less than $4 billion a year, every year, for the foreseeable future.

The report includes reams of detail but predictably leaves out some of the coolest and most important stuff, including any mention of three new stealth drones and the specially-modified Unmanned Aerial Vehicles the military operates alongside the Central Intelligence Agency.

The result is a 30-year drone map with some huge blank spaces

. Defense Department art

Defense Department art

Defense Department art

Defense Department art

These are not the Predators and Reapers you’re looking for

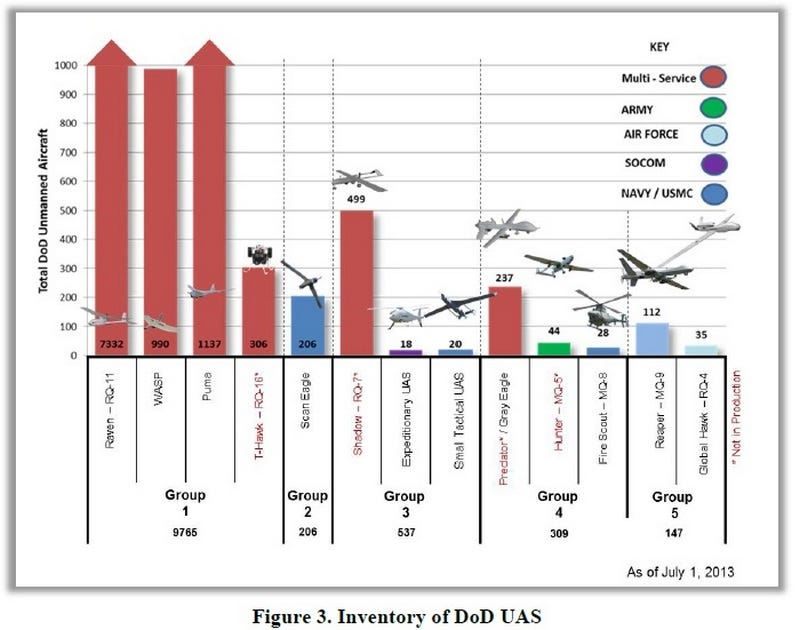

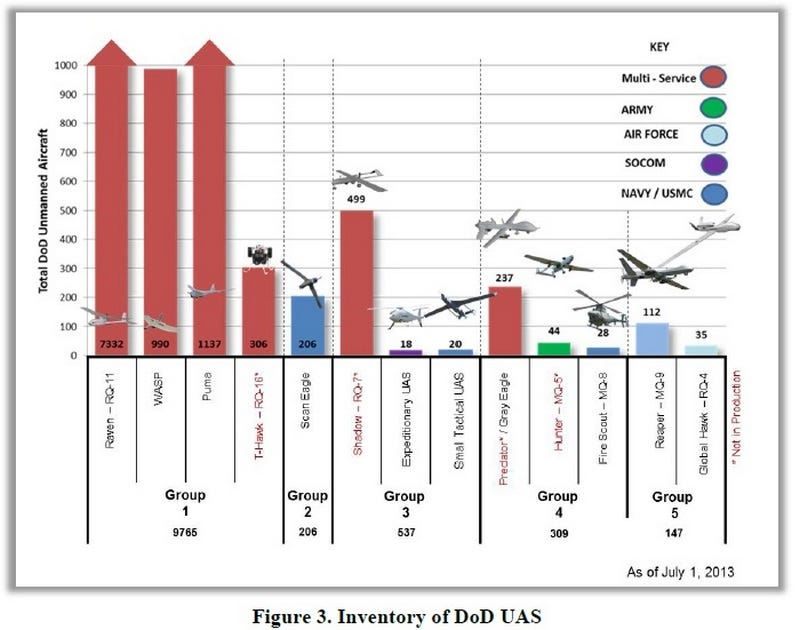

The report, formally entitled “Unmanned Systems Integrated Roadmap,” lists 11,000 aerial drones in the arsenals of the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps. Most are small, hand-launched Ravens, but the flying-robot population also includes 237 MQ-1Bs and MQ-1Cs plus 112 MQ-9s—the propeller-driven, missile-armed Predators, Gray Eagles and Reapers, respectively, that most people picture when they hear the word “drone.”

All three models are built by General Atomics.

The Air Force operates the listed MQ-1Bs and MQ-9s and the MQ-1Cs belong to the Army. But there’s another user of killer drones: the CIA, which reportedly controls no fewer than 80 specially-modified Predators and Reapers, apparently for patrols and air strikes over Yemen, Pakistan, Somalia and other battle zones.

Sources told Defense News that the CIA ‘bots have more-powerful four-blade propellers instead of the two blades on a standard Predator and three on a normal Reaper. The Agency UAVs also have better sensors than their strictly military counterparts, according to the trade publication.

The CIA does not technically own its Predators and Reapers—they’re formally part of the Air Force and are steered via satellite by Air Force operators in Nevada—but for all practical purposes the special Predators and Reapers belong to the CIA and fly only on Agency missions. In any event, they are not mentioned anywhere in the 30-year roadmap. RQ-170 in Afghanistan. Via UAS Vision

RQ-170 in Afghanistan. Via UAS Vision

RQ-170 in Afghanistan. Via UAS Vision

RQ-170 in Afghanistan. Via UAS Vision

Missing in Action: the RQ-170 Sentinel, RQ-180 and Avenger

Also omitted from the report are three secretive jet-powered drone types that, like the special Predators and Reapers, are in the Air Force arsenal but might fly on CIA missions. They include the RQ-170 Sentinel, which was famously outed in Afghanistan in 2009 and, a little over a year later, turned up in Tehran’s hands after one crashed along the Iran-Afghanistan border.

Lockheed Martin built 20 or so RQ-170s for the Air Force and CIA in the early 2000s. The approximately 60-foot-wingspan UAV with the radar-evading features helped spy on Iraq before the 2003 U.S.-led invasion and, in addition to spying on Iran, flew overhead Osama Bin Ladin’s compound in Pakistan during the 2011 raid by U.S. Navy SEALs that killed the terrorist leader.

RQ-170s were photographed several times by reporters in Afghanistan. Normally based in Nevada, the Sentinel-operating 30th Reconnaissance Squadron was touring U.S. bases in Guam and South Korea when the Pentagon decided in December 2009 to cop to the secret robot’s existence. Although it remains in the arsenal and is no longer classified, the Sentinel is not listed in the Pentagon’s drone roadmap.

Nor is the RQ-170’s apparent successor, the much larger and stealthier RQ-180, built by Northrop Grumman starting in 2008 and reportedly undergoing final testing in Nevada. Aviation Week reporters Bill Sweetman and Amy Butler revealed the RQ-180’s existence in December 2013 after months of research. The Air Force declined to confirm the journalists’ findings.

The RQ-180’s omission from the robot roadmap is a big deal, considering how important the new drone clearly is to the Pentagon and CIA’s long-term plans. Smart, stealthy and high-flying, the 130-foot-wingspan RQ-180 could replace many of today’s less capable aerial ‘bots and allow the Air Force and the intelligence agency to spy on even the most heavily-defended enemies.

The RQ-180’s quick progress is the apparent reason the Air Force cancelled several other major drone development programs—most notably the MQ-X, a replacement for the Predator and Reaper—and wants to curtail even more, including the RQ-4 Global Hawk, which is already in service but lacks the RQ-180’s stealth.

It also appears that the flying branch intends the RQ-180 to fly alongside the future Long Range Strike Bomber, helping spot targets for the huge new warplane once the latter enters service in the 2020s.

Only somewhat less glaring is the drone roadmap’s failure to mention the Air Force’s acquisition of a single jet-propelled Avenger UAV from General Atomics in late 2011. Essentially a faster Predator with an internal weapons bay, the Avenger is reportedly stealthier than a Predator but less able to evade detection than an RQ-170 or RQ-180 is.

The flying branch initially said it would send its Avenger to Afghanistan but did not say exactly why—although basing the drone in Afghanistan would put it within range of Pakistan and Iran for CIA missions. It’s for that reason that the RQ-170s are frequent visitors to Afghanistan. But after the crashed Sentinel turned up in Iran in December 2011, the Air Force backtracked, insisting there was no intention to deploy the Avenger to Central Asia.

And since then, very little has been published about the Air Force’s Avenger. The new robot roadmap perpetuates the silence about it and a host of other vitally important drones.

No comments:

Post a Comment